Harvard Health Blog

Expert panel says “no” to widespread testing for Alzheimer’s, dementia

A new report from the Alzheimer’s Association says that as many as 5 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease or some other form of dementia. Every 67 seconds someone in the United States develops Alzheimer’s disease or dementia. That’s 470,000 Americans this year alone.

Given that these thieves of memory and personality are so common and so feared, should all older Americans be tested for them? In proposed guidelines released yesterday, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force said “no.” Why not? Even after conducting a thorough review of the evidence, the panel said that there isn’t enough solid evidence to recommend screening, especially since not enough is known about the benefits and the harms.

Screening means testing a seemingly healthy person for signs of a hidden disease, like Alzheimer’s or cancer.

Why is early testing for Alzheimer’s and dementia not recommended when early testing for something like breast cancer is recommended? In part it has to do with treatment. While there are effective treatments for cancer, such as chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery, so far there aren’t any truly effective approaches to stop the forward progress of dementia. While some medications can slow the progress of Alzheimer’s disease, their side effects can be damaging.

“There are certain diseases in which we know that early detection can lead to early intervention, which can stave off worse outcomes, but if you don’t have any kind of disease-modifying therapy at hand, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to screen people who don’t have symptoms,” Dr. Aaron Philip Nelson, assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School and author of The Harvard Medical School Guide to Achieving Optimal Memory told me for an article that appears in the April 2014 Harvard Women’s Health Watch.

Testing for dementia

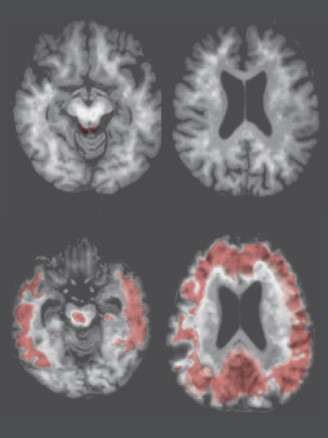

Checking people who have no symptoms of dementia using questionnaires, blood tests, or brain scans has long been controversial. One key sticking point is that tests available today can’t paint an accurate picture of future dementia risk. “There’s no test that can tell you that somebody is definitely going to get Alzheimer’s disease,” says Dr. Deborah Blacker, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Gerontology Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital.

There is one gene test, but it’s for a rare type of Alzheimer’s disease known as familial early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. It accounts for less than 5% of total cases, and typically starts before middle age. Even getting a brain scan to look for the clumps of protein known as amyloid plaques that are characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease can’t accurately predict a future diagnosis.

When you should be tested

If testing healthy adults every few years isn’t worthwhile, when does it make sense to test for dementia? When someone shows signs of memory loss, difficulty thinking, or other signs of so-called cognitive impairment, say experts. Individuals and their loved ones need to be alert to changes in memory and function. Doctors should also be aware of differences in their patients’ mental abilities. When someone has symptoms, they should get an evaluation, Dr. Blacker says.

Yet memory can naturally start to slip as you get older, and it can sometimes be hard to tell whether lapses are due to normal age-related memory loss or true mental impairment. Here’s a guide to help tell the difference:

| What’s normal | See your doctor if… |

| You forget the name of your high school science teacher | You forget the name of your best friend or grandchild |

| You make a mistake while balancing your checkbook | You often forget to pay your bills |

| You get lost when visiting a new doctor | You get disoriented in your own neighborhood |

| You forget what day it is, but soon remember | You keep forgetting the date and lose track of time |

| You sometimes have trouble finding the right word | You regularly have trouble finishing sentences, or you often use the wrong names for things |

| You misplace things like your car keys, but you can retrace your steps to find them | You often lose things and can’t retrace your steps to find them |

Knowing for sure

If you—or one of your loved ones—have noticed that you’ve been having memory lapses or other signs of cognitive impairment, see your primary care provider. You’ll get a series of tests to check how well your brain and nervous system work. You’ll also be asked questions to gauge your short-term recall, attention, and language skills.

Keep in mind that Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia aren’t the only causes of memory loss. Conditions like an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) or vitamin deficiency can also interfere with mental function. Poor sleep, depression, and stress can affect memory, too.

Improving memory might be as easy as getting more sleep or having a medical condition treated. If you are diagnosed with early-stage memory loss, your doctor can guide you through the next steps, lay out your options, let you know what to expect, and help you and your family plan for the future.

About the Author

Stephanie Watson, Former Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.