Harvard Health Blog

Untangling the non-invasive breast cancer controversy

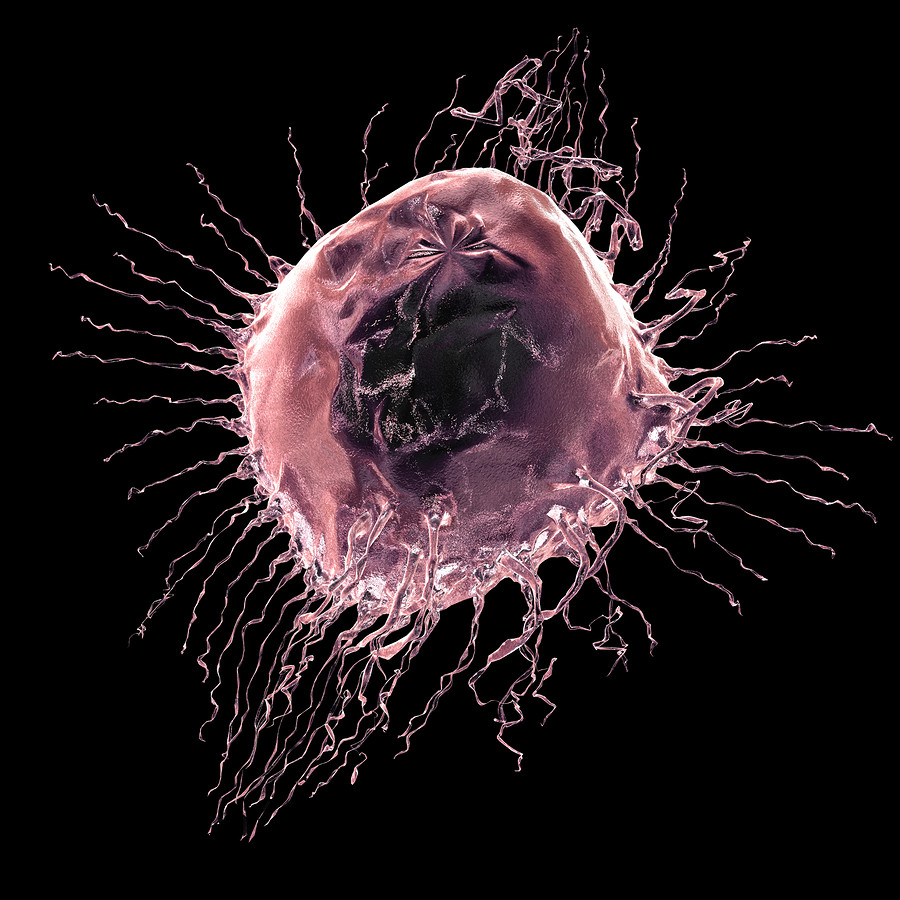

The most common type of non-invasive breast cancer is called ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Traditionally, DCIS is diagnosed when cancer cells seen under the microscope are localized only to the breast's duct system but have not invaded surrounding tissue.

The standard treatment for DCIS is to remove the affected tissue, making sure that there are no cancer cells left within the breast ("clear margins"). That surgery might be a mastectomy or a lumpectomy, which may be followed with radiation therapy.

DCIS carries an excellent prognosis. That's why this non-invasive cancer is also called "stage 0" breast cancer.

Reconsidering the best treatment for DCIS

Last month, JAMA Oncology published a study that suggests the standard treatment may be too aggressive. Perhaps some women with DCIS would do just as well without lumpectomy or mastectomy. As expected, this has generated a lot of controversy and confusion.

The researchers studied more than 108,000 women who had been diagnosed with DCIS at some point during a 20-year period. They found that women who received a lumpectomy followed by radiation had a lower risk of cancer returning in the affected breast. But the addition of radiation did not change the ultimate rate of death due to breast cancer. Nor did performing a mastectomy instead of a lumpectomy.

This type of research is known as an observational study. Observational studies can show possible associations between therapies and outcomes. They don't prove that one therapy is actually better.

Because this was an observational study, there are many questions about what could have affected the study outcomes. These include why each specific treatment was chosen for each patient, the accuracy of the DCIS diagnoses, whether each surgery truly had "clear margins," and the quality of follow-up care, including regular mammograms to watch for the possible return of cancer.

In addition, this study didn't document which patients, if any, also received hormonal therapy such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors. These treatments can help prevent recurrence. For these reasons, it is hard to interpret these study data, and even harder to use that information when deciding how to treat any one woman with DCIS.

What this study does tell us is that not all DCIS is the same. In this study, approximately 500 patients died of breast cancer without ever having invasive cancer in the breast. This suggests that for some very small subset of women, distant or metastatic disease occurred despite treatment of DCIS — a concerning finding.

Also, death rates were higher for women diagnosed with DCIS before the age of 35, and for black women compared to non-Hispanic white women. This suggests that these women may need more aggressive intervention.

The good news: The study also reaffirmed the fact that overall, mortality associated with DCIS is exceedingly low. Fewer than 1% of patients in this 20-year study died from breast cancer.

Did the media send the wrong message about the study results?

Some media coverage of this study tended to leave the impression that DCIS doesn't need to be treated. In fact, all patients in the study received some form of treatment. What the study does say is that none of the specific treatments the researchers compared against each other (lumpectomy with or without radiation or mastectomy) differed very much from one another with respect to ultimate survival.

Ongoing trials are looking at whether "watchful waiting" may be reasonable for certain women — that is to say, closely following low-risk patients (for example, those with small tumors or low- to intermediate-grade cancers) to determine if and when treatment is needed. However, we don't have those results yet.

For some women, DCIS is a "precursor" to invasive breast cancer, but in many others, it may not progress. Yet right now, we don't understand these cancers well enough, nor can we accurately predict the biological behavior of these abnormal cells for any given woman. More research is necessary to determine the specific optimal treatment for each individual woman diagnosed with DCIS.

Ultimately, decisions about the diagnosis and treatment of DCIS must be made by a woman and her doctor and must take into account certain risk factors (age and race among them), as well as that woman's personal preferences in the face of the limitations of current scientific knowledge. I expect that results from ongoing and future research will soon allow physicians to better guide these difficult decisions. Fortunately, the bottom line for DCIS is that no matter what treatment is pursued, the outcomes are excellent for the majority of patients.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.