Abundance of fructose not good for the liver, heart

Another reason to avoid foods made with a lot of sugar.

The human body handles glucose and fructose — the most abundant sugars in our diet — in different ways. Virtually every cell in the body can break down glucose for energy. About the only ones that can handle fructose are liver cells. What the liver does with fructose, especially when there is too much in the diet, has potentially dangerous consequences for the liver, the arteries, and the heart.

Fructose, also called fruit sugar, was once a minor part of our diet. In the early 1900s, the average American took in about 15 grams of fructose a day (about half an ounce), most of it from eating fruits and vegetables. Today we average four or five times that amount, almost all of it from the refined sugars used to make breakfast cereals, pastries, sodas, fruit drinks, and other sweet foods and beverages.

Refined sugar, called sucrose, is half glucose and half fructose. High-fructose corn syrup is about 55% fructose and 45% glucose.

From fructose to fat

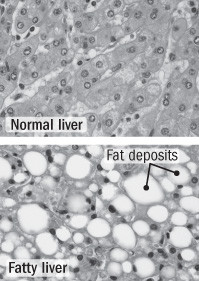

The entry of fructose into the liver kicks off a series of complex chemical transformations. (You can see a diagram of these at health.harvard.edu/172.) One remarkable change is that the liver uses fructose, a carbohydrate, to create fat. This process is called lipogenesis. Give the liver enough fructose, and tiny fat droplets begin to accumulate in liver cells (see figure). This buildup is called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, because it looks just like what happens in the livers of people who drink too much alcohol.

Virtually unknown before 1980, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease now affects up to 30% of adults in the United States and other developed countries, and between 70% and 90% of those who are obese or who have diabetes.

Early on, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is reversible. At some point, though, the liver can become inflamed. This can cause the low-grade damage known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (steato meaning fat and hepatitis meaning liver inflammation). If the inflammation becomes severe, it can lead to cirrhosis — an accumulation of scar tissue and the subsequent degeneration of liver function.

Liver comparison

|

Beyond the liver

The breakdown of fructose in the liver does more than lead to the buildup of fat. It also:

-

elevates triglycerides

-

increases harmful LDL (so-called bad cholesterol)

-

promotes the buildup of fat around organs (visceral fat)

-

increases blood pressure

-

makes tissues insulin-resistant, a precursor to diabetes

-

increases the production of free radicals, energetic compounds that can damage DNA and cells.

None of these changes are good for the arteries and the heart.

Researchers have begun looking at connections between fructose, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular disease. The early results are in line with changes listed above due to the metabolism of fructose.

An article published in 2010 in The New England Journal of Medicine indicated that people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are more likely than those without it to have buildups of cholesterol-filled plaque in their arteries. They are also more likely to develop cardiovascular disease or die from it. In fact, people with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are far more likely to die of cardiovascular disease than liver disease.

A report from the Framingham Heart Study has linked nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with metabolic syndrome, a constellation of changes that is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease. Other studies have linked fructose intake with high blood pressure.

Limit added sugars

Experts still have a long way to go to connect the dots between fructose and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. Higher intakes of fructose are associated with these conditions, but clinical trials have yet to show that it causes them.

Still, it's worth cutting back on fructose. But don't do it by giving up fruit. Fruit is good for you and is a minor source of fructose for most people. The big sources are refined sugar and high-fructose corn syrup.

The American Heart Association recommends limiting the amount of sugar you get from sugar-sweetened drinks, pastries, desserts, breakfast cereals, and more, mainly to avoid gaining weight. The same strategy could also protect your liver and your arteries.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.