When sex gives more pain than pleasure

Dyspareunia is a common problem for many postmenopausal women.

Millions of women experience pain before, during, or after sexual intercourse—a condition called dyspareunia (from the Greek dyspareunos, meaning "badly mated"). This condition not only saps sexual desire and enjoyment, it can also strain relationships and erode quality of life in general. For postmenopausal women, dyspareunia may also raise concerns about aging and body image.

Many women suffer in silence and don't seek the help they need, or they have trouble finding a clinician who can diagnose and treat the causes of their pain. That is unfortunate, because treatments are available for many of the problems that underlie this vexing condition.

What is it?

Dyspareunia (pronounced dis-pah-ROO-nee-uh) can happen at any age, but it's particularly common among women who've reached menopause. Studies and surveys suggest that one-quarter to one-half of postmenopausal women experience some pain during sex. The pain can range from mild to excruciating; sufferers describe it as burning, stinging, sharpness, or extreme tenderness. Depending on its cause, pain may be located in the outer genitals (vulva), within the vagina, or deep in the pelvis. Many women feel discomfort mainly in the vestibule, the nerve-rich area surrounding the vaginal opening. Dyspareunia can start suddenly or develop gradually. Pain may occur every time with sex, or only occasionally. For some women, simply thinking about intercourse can start a cycle of tightness, pain, and avoidance of sex.

What causes it?

Possible causes include hormonal changes, various medical or nerve conditions, and emotional problems such as anxiety or depression. Often, many are at work. One thing can easily trigger a cascade of problems.

Vaginal atrophy, the deterioration of vaginal tissue caused by estrogen loss, is a major source of painful intercourse for women at midlife. When ovarian production of estrogen declines at menopause, vaginal tissue may become thinner, less lubricated, and less elastic. Eventually these changes can result in vaginal dryness, burning, itching, and pain. (Reduced sexual activity as well as medications such as antihistamines can contribute to vaginal dryness.)

Another culprit is vestibulodynia (also known as localized provoked vulvodynia), a chronic pain syndrome affecting the vestibule. Any kind of touch or pressure—not only from penetration but even from a tampon, cotton swab, tight jeans, or toilet tissue—can trig ger discomfort. Vestibulodynia is a type of vulvodynia, or unexplained and persistent pain in the vulvar area. The condition appears to have several different causes.

Other causes of pain with intercourse include skin diseases in the genital area, such as eczema and psoriasis; conditions such as endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, bladder prolapse, and infections of the urinary tract, vagina, or reproductive organs; certain cancer treatments; injury to the pelvic area from childbirth; reconstructive surgery; damage to the pudendal nerve, which supplies the vaginal area; musculoskeletal complaints, such as arthritis or tight hip or pelvic muscles; and some kinds of male sexual dysfunction (prolonged intercourse may increase vaginal friction and pain).

Psychological or emotional factors may be involved. Stress, anxiety, depression, guilt, a history of sexual abuse, an upsetting pelvic exam in the past, or relationship troubles can also be at the root of sexual pain. Some women experience vaginismus—involuntary clenching of vaginal muscles to prevent penetration. Vaginismus is especially common among women who associate the vaginal area with fear or physical trauma.

Diagnosing dyspareunia

If your primary care provider or gynecologist is not familiar with the problem, she or he may be able to refer you to someone with experience in treating dyspareunia. You can also search online or contact the gynecology department of the nearest medical center or teaching hospital.

Your clinician will ask about your pain—when it began, where and when it hurts, how it feels, and what you've done to relieve it—and may have questions about your relationship with your partner. She or he will also want to know about your gynecologic history (e.g., surgeries and childbirths) and any medical conditions or concerns.

The evaluation usually involves a thorough medical history and pelvic exam, and sometimes procedures or tests (such as laboratory tests for infections). The clinician will examine your vulva, vagina, and rectal area for redness, scarring, dryness, discharge, sores, growths, and other physical signs that might help explain your dyspareunia. She or he will probably use a cotton swab (to test for sensitivity to touch), a speculum, and gloved fingers during the exam. Understandably, women with sexual pain often worry about having a pelvic exam. Talk to your clinician about your concerns before the exam begins.

Lifestyle and self-careHere are some ways to manage vulvar discomfort and increase sexual pleasure. Lubricants. Nonhormonal vaginal lubricants and moisturizers may help reduce friction and pain during intercourse. (Lubricants are applied just before sex; moisturizers are applied more regularly, for longer-term relief.) There are many brands with different ingredients, and finding the products that work for you can take time. Vegetable oil is an inexpensive option; however, like other oil-based lubricants, it can weaken latex and shouldn't be used with condoms. Sexual techniques. Extend foreplay to increase moisture in the vaginal tissues before intercourse. Try switching positions. Experiment with different ways of being intimate. And communicate with your partner; speak up about what does and doesn't feel good. "Use it or lose it." Frequent sexual activity can help stretch and strengthen muscles and increase blood flow and lubrication. But if intercourse hurts, practice masturbation or different ways of being sexually intimate that don't involve penetration. Gentle vulvar care. Wash with mild soap or plain water, and pat dry. Avoid perfumed, multi-ingredient products such as bubble bath, douches, and some panty liners. Wear loose clothing and choose cotton underwear. Rinse the area with cool water after urinating. |

Treating dyspareunia

Treatment often requires a multifaceted approach that includes medications, other therapies, and self-care (see "Lifestyle and self-care"). If your clinician identifies any vaginal infections, skin ailments, or other treatable conditions, she or he will prescribe the appropriate antibiotics, topical corticosteroids, or other medications. Frequently prescribed strategies for managing dyspareunia include the following:

Vaginal estrogen. Topical low-dose estrogen helps most women with vaginal atrophy; it's also recommended in some cases of vestibulodynia and vulvar skin problems.

In treating vaginal atrophy, vaginal estrogen is preferred to systemic hormone therapy, which is taken in pill and other forms, with or without a progestin. Systemic hormone therapy has been associated with an increased risk for heart attacks in older women, stroke, and blood clots. Vaginal application releases little estrogen into the bloodstream, so it carries less risk of side effects than systemic estrogen. But discuss the pros and cons of vaginal estrogen treatment with your physician—especially if you have a history of breast cancer.

Lidocaine. This numbing agent may help ease sexual discomfort when applied as an ointment to the vestibule before and after sex. (If it's used before sex, it may affect the male.)

Surgery. Women with stubborn and severe vestibulodynia may want to consider an outpatient procedure called vulvar vestibulectomy, which removes some vestibular tissue. This surgery is usually offered only after other medical approaches have failed.

Counseling. Emotional and psychological issues, from anxiety to poor communication in a relationship, can contribute to painful sex, and painful sex can put stress on a relationship. Talking with a professional counselor or sex therapist may help.

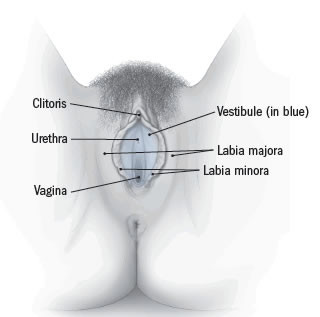

Anatomy of the vulva

The vulva consists of several layers that cover and protect the sexual organs and urinary opening. The outer lips of the vulva—the labia majora—contain fat that helps cushion the area. Inside the labia majora are the thinner flaps of skin called the labia minora, which join at the top to enclose the clitoris. The area between the labia minora, the vestibule, contains the openings to the urethra and the vagina. |

Pelvic floor physical therapy. Many women with vulvar pain have tight or weakened vaginal and pelvic floor muscles. These muscles can weaken as a result of aging, childbirth, excess weight, hormonal changes, and certain physical strains. They can also tighten in response to genital pain. Physical therapy can help reduce tightness and improve muscle function.

Your physical therapist will use hands-on techniques such as massage and gentle pressure to relax and stretch your tissues and promote blood flow, including (when you're ready) the interior of the vagina. You'll also learn exercises to help strengthen pelvic floor muscles and ease tightness in the hips. A biofeedback machine may be used to monitor your progress on a computer screen linked to a small sensor in your vagina. Therapy may take eight to 12 sessions before results are noticeable.

Additional informationNational Vulvodynia Association North American Menopause Society's Sexual Health & Menopause page |

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.