Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

- Reviewed by Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

What is antiphospholipid antibody syndrome?

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) is a condition defined by the presence of abnormal antibodies and a tendency to form blood clots or to have miscarriages.

People with antiphospholipid antibody syndrome produce antibodies that interact with certain proteins in the blood. This causes the blood to clot more than normal. The most commonly measured antiphospholipid antibodies include lupus anticoagulant and antibodies to cardiolipin or beta-2 glycoprotein.

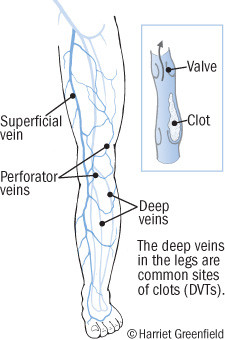

The blood clots often form in the leg veins. The clots also can form in arteries. The blood clots may occur in any organ, but they tend to favor the lungs, brain, kidneys, heart and skin.

There are two types of APS: primary and secondary. People with primary APS do not have any associated condition. The secondary form is associated with another immune disorder, such as lupus, an infection or, rarely, the use of a medication (such as chlorpromazine or procainamide).

A person may have a blood test that detects antiphospholipid antibodies. This does not necessarily mean that he or she has APS or will develop symptoms or problems of APS.

Symptoms of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

The symptoms of APS can include any of the following:

Nervous system. APS can cause:

- Sneddon's syndrome, a condition in which the affected person has repeated strokes. They also have a mottling of the skin that is lacy purple and white.

- a syndrome similar to multiple sclerosis. They can have:

-

- stroke

- slurred speech

- difficulty understanding or forming words

- change in vision

- weakness on one side of the body

- involuntary jerking movements of the arms or legs

- dementia

- migraines

- difficulty urinating

- difficulty walking

- double vision

- numbness.

Heart and blood vessels. APS can lead to:

- heart attacks (up to 20% of younger people who have a heart attack have antiphospholipid antibodies)

- heart valve problems that can mimic bacterial endocarditis

- blood clots in the upper chambers of the heart

- deep vein thrombosis (blood clot in a vein) that can pain and swelling in a leg or arm; these clots can travel to the lungs (see below) and cause difficulty breathing or even death.

|

|

Blood cells. Some people with a condition called immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) have antiphospholipid antibodies. The primary problem in ITP is low platelets, the blood cells that aid clot formation and prevent excessive bleeding. Over time, some people with ITP develop APS. People with ITP and APS can have problems with excessive clotting and excessive bleeding.

Also, red blood cells can break down abnormally. This may cause fatigue, dizziness, and pale skin. This is more common in people with lupus and secondary APS.

Lung. Blood clots in the lung can cause

- repeated clots can cause elevated pressure in the blood vessels around the lungs. This may cause the person to be constantly short of breath.

- chest pain

- shortness of breath

- rapid breathing.

Gastrointestinal. APS can affect the blood supply to the intestines, causing

- abdominal pain

- fever

- blood in the stool.

APS can cause a condition called Budd-Chiari syndrome. In this syndrome, a blood clot prevents blood from flowing out of the liver. The person may experience

- nausea

- vomiting

- jaundice (yellow skin)

- dark urine

- pale stool

- swelling of the abdomen.

Kidneys. Blood clots that affect the kidneys can cause kidney damage and blood in the urine.

Skin. APS can cause

- purple and white mottling of the skin

- repeated sores (ulcers)

- repeated bumps (nodules)

- tissue in the fingertips to die (gangrene).

Eyes. Veins or arteries in the retina can be affected. This can cause blurring or loss of vision.

Pregnancy. APS can cause problems for the pregnant woman such as stroke or blood clots in the lungs.

APS may be associated with a syndrome of pregnancy known as HELLP. HELLP stands for hemolysis (breakdown of red blood cells), elevated liver tests and low platelets.

In addition, APS may be complicated by

- recurrent miscarriage which can occur early or late in pregnancy

- a partial or complete separation of the placenta from the uterus before the baby is born

- a small placenta

- premature birth.

Diagnosing antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Many symptoms that occur with APS are common even without the condition. They do not necessarily mean APS is the cause.

However, a doctor may order tests to detect the antibodies associated with APS (including lupus anticoagulant and antibodies to cardiolipin or beta-2 glycoprotein) when

- blood clots or miscarriages occur for no apparent reason

- a young person has a heart attack or stroke.

People with antiphospholipid antibodies may have a positive screening test for syphilis even though they do not have the disease. Fortunately, confirmatory tests are available to rule out syphilis infection in a person with antiphospholipid antibodies.

Expected duration of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Some people with APS continue to have symptoms off and on throughout their lives. Others improve without any repeat episodes.

Some people even lose the antibodies associated with the syndrome. This can happen with primary APS. But it is especially common

- after a viral infection

- in women who recently were pregnant

- when a medication suspected to be associated with APS is no longer used.

Preventing antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

There is no known way to reliably prevent APS, although vaccination for viral infections (including influenza) could reduce the risk of APS triggered by viral infection. However, lifestyle changes can reduce the likelihood of blood clots.

To reduce your risk of blood clots:

- Quit smoking.

- Increase physical activity.

- Avoid medications (if possible) that are suspected of increasing the risk of blood clots or causing APS; discuss this with your doctor before stopping any medications.

Treating antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

If you have antiphospholipid antibodies but have not had blood clots or a miscarriage, your doctor may recommend that you take a low-dose aspirin every day. However, aspirin therapy may not be effective at preventing clots, and it may increase your risks of bleeding or stomach problems.

For people with a history of blood clots as part of APS, doctors usually prescribe a powerful blood thinner called warfarin (Coumadin). This medication usually is taken for life. People who take warfarin need to have their blood tested regularly. That's because if the blood is too thin, the risk of bleeding increases. If it is not thin enough, clotting is more likely. Other blood thinners (including dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban) appear to be less effective than warfarin. Aspirin may be added to warfarin, especially if the clot was in an artery.

Another commonly used blood thinner is called heparin. It may be used before you start taking warfarin. Heparin also is used for pregnant women, because warfarin is not safe for the developing fetus. Heparin is only available as an injection.

A woman with APS who is trying to become pregnant after repeated miscarriages may increase the chance of a successful pregnancy by getting heparin injections and taking low-dose aspirin. This treatment should start as soon as the pregnancy is discovered. It continues until just before delivery.

Other medications may be recommended for advanced cases of APS include:

- steroids

- immune-suppressing drugs (such as rituximab or eculizumab)

- intravenous immune globulin (an injection of antibodies pooled from blood donors)

- plasma exchange (a blood filtering procedure)

- statin medications

- hydroxychloroquine.

However, the benefits of these medications as primary treatment have not been proven but may be added to other treatments (such as warfarin) if the condition has been difficult to treat.

When to call a professional

Contact a doctor if you have any symptoms of APS such as unexplained leg swelling or shortness of breath. Call your doctor if you have APS and want to become pregnant.

Prognosis

People with primary APS generally lead normal, healthy lives with the help of medication and lifestyle changes.

People with secondary APS generally have a similar prognosis. But their illnesses and life spans can be affected by associated conditions. APS associated with infections or medication use may be temporary and resolve once the infection subsides or a medication is stopped.

Some people with APS will have repeated blood clots despite the best treatments. This is referred to as catastrophic antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, a condition that, as the name suggests, can be fatal.

Additional info

American College of Rheumatology

http://www.rheumatology.org/

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

http://www.niams.nih.gov/

National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD)

http://rarediseases.org/

About the Reviewer

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.