Osteoarthritis

- Reviewed by Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

What is it?

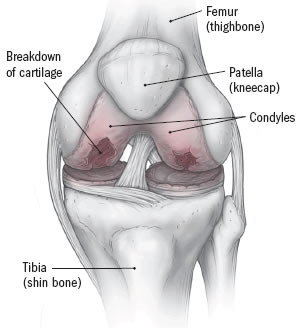

Inside a joint, a tissue called cartilage cushions the joint and prevents the bones from rubbing against each other. Osteoarthritis occurs when the cartilage of a joint erodes (breaks down). Bones begin to rub against each other, causing pain and difficulty moving the joint. Osteoarthritis also can affect nearby bones, which can become enlarged in places. These enlargements are called bone spurs or osteophytes.

Although the term arthritis means joint inflammation, there is relatively little inflammation in the joints of most people with osteoarthritis. For this reason, and because this type of arthritis seems to be caused by age-related degeneration of the joints, many experts and health care professionals prefer to call it degenerative joint disease.

Osteoarthritis can range from mild to severe. The pain associated with osteoarthritis can be significant and it usually is made worse by movement. Osteoarthritis can be limited to one joint or start in one joint usually the knee, hip, hand, foot or spine or it can involve a number of joints. If the hand is affected, usually many joints of the fingers become arthritic.

Osteoarthritis probably does not have a single cause, and, for most people, no cause can be identified. Age is a leading risk factor, because osteoarthritis usually occurs as people get older. However, research suggests that joints do not always deteriorate as people age. Other factors seem to contribute to osteoarthritis. Sports-related injuries or repeated small injuries caused by repeated movements on the job may increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis. Genetics also plays a role. Obesity seems to increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis of the knees.

Other factors that increase the risk of osteoarthritis include:

- repeated episodes of bleeding into the joint, as may occur in hemophilia or other bleeding disorders

- repeated episodes of gout or pseudogout, in which uric acid or calcium crystals in the joint cause episodes of inflammation

- avascular necrosis, a condition in which the blood supply to the bone near the joint is interrupted, leading to bone death and eventually joint damage; the hip is affected most often

- chronic (long-lasting) inflammation caused by previous rheumatic illness, such as rheumatoid arthritis

- metabolic disorders, such as hemochromatosis, in which a genetic abnormality leads to too much iron in the joints and other parts of the body

- joint infection.

One theory is that some people are born with defective cartilage or slight defects in the way joints fit, and as these people age, they are more likely to have cartilage in the joint break down.

Women are affected by osteoarthritis slightly more often than are men.

Osteoarthritis is one of the most common medical conditions, affecting an estimated 15.8 million people in the United States. In many people, it goes unrecognized. It is estimated that as many as half of all those who have osteoarthritis do not know that the pain and stiffness they are experiencing are symptoms of osteoarthritis.

Symptoms

Symptoms of osteoarthritis include:

- joint pain with or without swelling, often worse after activity

- limited flexibility, especially after not moving for a while

- bony lumps at the end of fingers, called Heberden's nodes, or on the middle joints of fingers, called Bouchard's nodes

- a grinding sensation when the joint is moved

- numbness or tingling in an arm or leg, which can happen if the arthritis has caused bone changes that are putting pressure on a nerve; for example, in the neck or lower back.

People who have osteoarthritis often complain of a deep ache, centered in the joint. Typically, the pain is aggravated by using the joint and relieved by rest. However, as the disease worsens, the pain becomes more constant. Often, when the pain is significant during the night, it interferes with sleep.

Diagnosis

Your doctor may ask about osteoarthritis in your parents, because osteoarthritis appears to have a genetic component.

He or she will examine you, looking for tenderness, warmth and swelling around the joint or joints. Your doctor may order X-rays, but osteoarthritis may not be apparent in its earliest stages and many people have osteoarthritis by x-ray in joints despite having no symptoms. Your health care professional also may order blood tests to look for evidence of another arthritic condition.

Expected duration

Osteoarthritis is a long-lasting condition that usually gets worse slowly over time.

Prevention

There is no reliable way to prevent most cases of osteoarthritis. However, you may be able to control some factors that increase the risk of developing the disease. You can

- maintain an ideal body weight

- prevent major accidents and injuries.

It may also help to prevent or treating any conditions that might contribute to joint damage, such as hemochromatosis, gout, or infection.

Treatment

Treatment focuses on managing pain and maintaining the ability to use the joint.

An over-the-counter painkiller, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), can help to ease pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin and others) or naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn and others) also may help. However, NSAIDs may be unsafe for people at high risk of developing ulcers, including people who have had ulcers in the past and the elderly. For these people, newer medications called cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, such as celecoxib (Celebrex), may be less irritating to the stomach and intestines but has similar effectiveness as older medicines. Stomach problems, including ulcers, are the most common side effects of these medications but there are others, including an increased risk of cardiovascular problems.

In some instances, when inflammation is significant, your health care professional may remove fluid from the joint and inject the joint with a corticosteroid drug. However, these drugs can damage the joint if they are used too much, so your health care professional will limit their use.

Another approved treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee is hyaluronate injections. Hyaluronate is a natural substance in joints that provides lubrication. The injectable hyaluronate drugs are synthesized forms that can be injected one time or weekly for three to five weeks. Some studies suggest that these injections help, although others have found no benefit.

Studies also suggest that an over-the-counter supplement called glucosamine sulfate is safe and may provide modest benefit to people with osteoarthritis of the knees. However, there is no compelling evidence that joint deterioration can be slowed or stopped by treatment with glucosamine. Over-the-counter creams containing capsaicin applied to the skin over painful joints also may help.

Applying heat or cold can relieve pain temporarily. Your doctor also can advise you on the use of heating pads, hot baths and ice packs to ease the discomfort.

Your doctor likely will suggest that you perform certain exercises to reduce stiffness and improve your ability to move the joints. Because extra pounds put pressure on sensitive joints, it is important that you lose excess weight. In addition, if you have osteoarthritis of the spine, it is important to maintain good posture to distribute weight and pressure evenly throughout the body. Physical therapists can be helpful in recommending (and supervising) an exercise program and measures to reduce joint stress.

In severe cases where deterioration is significant, your doctor may recommend surgery to correct deformity in a joint or to reconstruct or replace a hip or knee joint.

When to call a professional

Call your doctor if you have joint pain, a grinding sensation in joints or limited joint motion.

Prognosis

When treated properly, symptoms of osteoarthritis can usually be well-controlled. However, it is a long-lasting disease that may require ongoing care and possible changes in treatment over time.

Additional info

Arthritis Foundation

https://www.arthritis.org/

American College of Rheumatology

https://www.rheumatology.org/

About the Reviewer

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.