Farewell to the fasting cholesterol test?

At a recent meeting I offered a visitor lunch which she declined with obvious regret. She was hungry, and it was noon. But she was headed to her annual physical, and eating beforehand would mean returning another morning for a fasting cholesterol level. Most of us can relate to her annoyance, but thankfully this may soon be a thing of the past.

Doctors have traditionally ordered cholesterol tests to be drawn after an overnight fast. But this requirement causes a significant burden on both sides of the health care equation. Most people hate to fast. Skipping meals is particularly difficult for active people, people with diabetes, and children. Yet coming back for another visit is even more of a hassle, so many people just don't bother. And it has been a drain for doctors, too, resulting in repeat test orders, phone calls, and patient visits.

International guidelines published last month in the European Heart Journal became the latest official recommendation against routine fasting for cholesterol tests. These guidelines defend what many health care systems and many doctors (including me) have been practicing for several years already. They should be met with universal acceptance, even if takes a while. There are several scientific reasons supporting this change.

The history behind fasting cholesterol tests

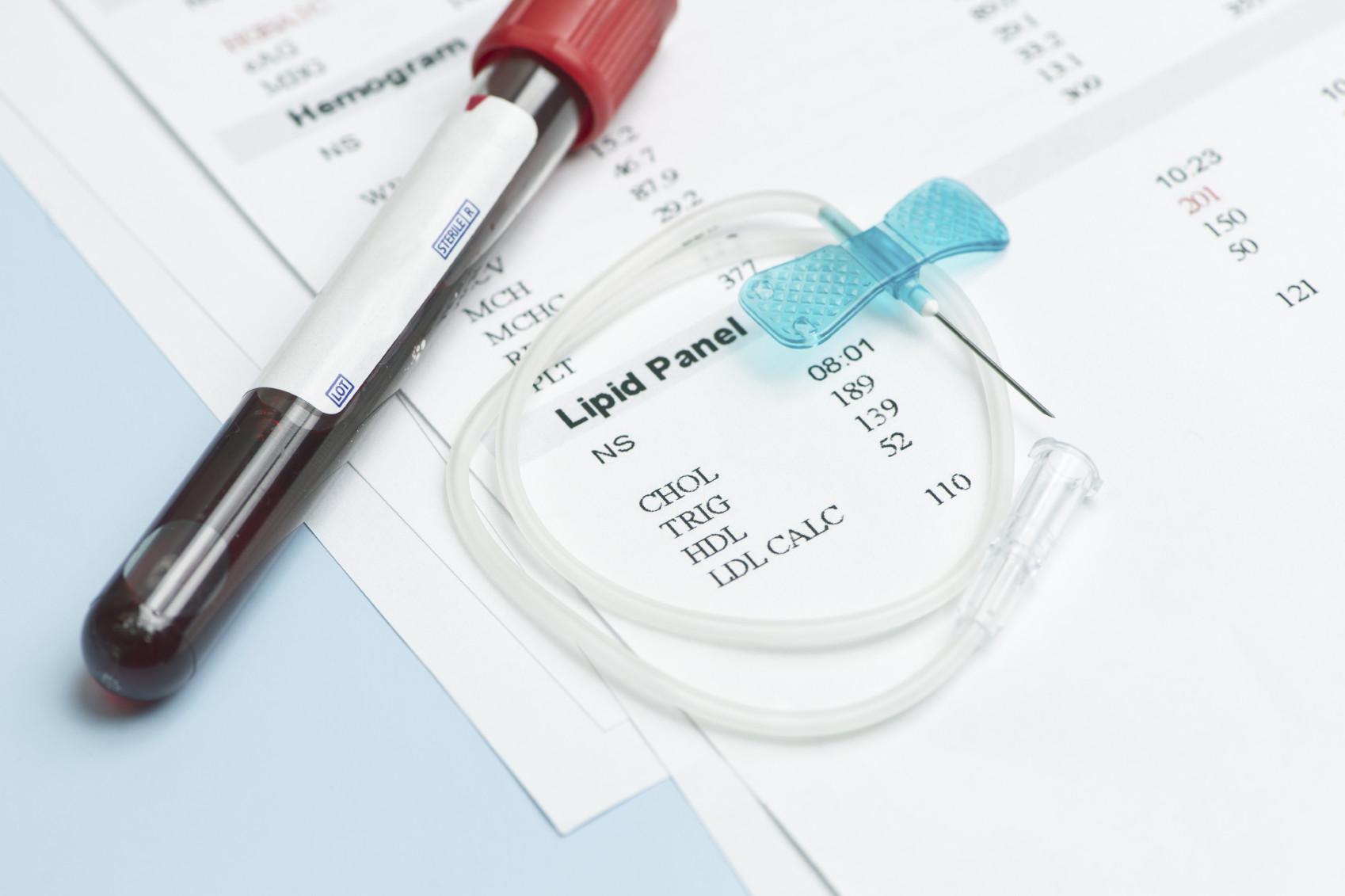

When doctors test for cholesterol, we almost always order a group of tests called a lipid panel (lipids are fat-containing molecules). This panel typically includes four separate measures:

- Total cholesterol concentration.

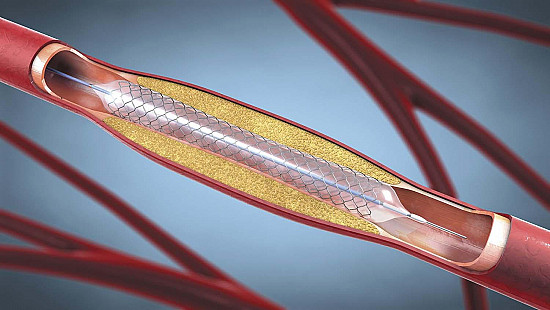

- Low-density lipoprotein* (LDL) - cholesterol, often called the "bad" cholesterol. The amount of LDL in your blood strongly predicts your risk of cardiovascular disease, as higher levels are associated with development of plaque in the arteries.

- High-density lipoprotein (HDL) - cholesterol, often called "good cholesterol" because higher levels protect against heart disease.

- Triglycerides (a different type of lipid molecule). High levels of triglycerides are also associated with vascular disease, although this relationship isn't as well defined.

*Lipoproteins are the "packages" that transport cholesterol in the bloodstream.

Lipids have traditionally been drawn after a fast for two main reasons. The first was to minimize variation, since eating can affect some lipid levels. The second was to produce a better calculation of LDL-cholesterol, which is often derived from an equation thought to provide highly distorted results after eating. However, more recent studies have largely negated these concerns.

Scientists now agree that eating has only slight, clinically insignificant effects on three parts of the lipid profile: total cholesterol, and both HDL- and LDL-cholesterol. Food does raise triglyceride levels for several hours, usually to a modest degree. After a high fat meal these increases can be striking. Therefore, a doctor may still order a fasting test of triglycerides if non-fasting values are significantly elevated.

Perhaps more important, large-scale analyses have shown that non-fasting lipids don't weaken the connection between cholesterol levels and harmful events like heart attack and stroke. In fact, post-meal measures are thought to strengthen the ability of lipid levels to predict cardiovascular risk. This observation may stem from the fact that most people eat several meals plus snacks during the day. That means we spend most of our time in a "fed" state, not a fasting state. So lipid levels after eating may best reflect our normal physiology.

An end to the dreaded overnight fast?

Guidelines for lipid panels have evolved over the past decade, supported by evidence from studies involving hundreds of thousands of people. Most recommendations now support non-fasting cholesterol tests for routine testing. (You can find a summary of these recommendations here.)

Some fasting lipids tests will remain necessary, especially in people with very high triglycerides. And some people will still need to fast for blood sugar levels, although an alternative test for diabetes (hemoglobin A1c) has replaced much of this testing. But for most, including those having routine cholesterol tests to weigh cardiovascular risk and for those taking drug therapy, this news is good news.

So ask your doctor if you really need to skip breakfast before your next blood draw. Traditions die hard, but both science and convenience may ultimately steer this one to its end. This is one change doctors and patients should celebrate together.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.