Harvard Health Blog

Finding help for pelvic pain: A patient’s story

In the spring of 1996, André James* was under a great deal of stress. Married, with a young family to support, he was finishing his medical training at a big-city hospital and anxiously searching for a job. One day, he suddenly experienced severe testicular pain. It was as if someone grabbed both testicles and kept tightening his grip.

| *Editor’s note: To protect his privacy, the patient’s name and some biographical details have been changed. All medical details are as reported. A patient’s physicians are usually not named, per editorial policy, but James requested that some be included in this article, and the physicians agreed. |

Frightened, James immediately saw a urologist, who examined him, ran several tests, and declared that he could find nothing wrong. But he noted that he often saw police officers, who were under tremendous stress, with the same symptoms. Stress, the physician said, might have triggered James’ symptoms, but he prescribed an antibiotic just in case one of the tests had failed to detect a bacterial infection. It took two rounds of antibiotics and several weeks’ time, but the pain finally went away. And when James found a job at another hospital, the stress went away, too.

James forgot all about the problem until 2004, when he developed testicular pain again. This time, however, the pain was somewhat different. It moved from one testicle to the other and then migrated above his pubic bone. He urinated frequently, and when he did, he felt as if he were urinating boiling water. His penis hurt, and the pain grew more intense after he had sex. He saw another urologist, who did a complete workup. Once again, the doctor couldn’t find any obvious problems, and the laboratory tests all came back negative. The doctor concluded that James had chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS), a type of prostatitis. One possible cause: excessive tightness in the muscles of the pelvic floor (see Figure 1).

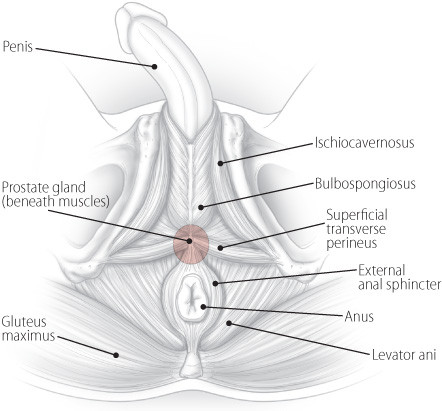

Figure 1: Pelvic floor muscles

|

The doctor prescribed lorazepam (Ativan), a drug often used as a muscle relaxant, and anti-inflammatory medications. He also suggested mild exercise, applying heat to the perineum, and sitting in a hot bath. The lorazepam worked best — just 1 milligram a day relieved James’ pain.

A year later, the pain was back. The lorazepam seemed to have stopped working, and urinating was uncomfortable at best. James underwent an ultrasound, an MRI scan, and a cystoscopy, a procedure during which a doctor inserts a device called a cystoscope into the urethra to examine the urinary tract. All the results came back negative. The doctor said that James’ pelvic muscles weren’t working properly, a condition he called pelvic floor syndrome. He suggested biofeedback, a technique that helps one become more aware of unconscious or involuntary bodily activities so that they can be consciously manipulated.

James saw a specialist in mind-body medicine, but the specialist tried a different technique. “He said, ‘You’ve developed a negative cycle between your brain and your pelvic floor. It’s like dealing with chronic pain. You just have to forget about your symptoms. Put them out of your mind. If you have pain, just tell the pain to go away and get on with your life,’” James recalled.

James decided to give it a try. He returned to his exercise routine at the gym. He also resumed having sex with his wife, which he had been avoiding. When he felt pain, he pushed it out of his mind. And for two years, he managed to keep the symptoms at bay.

But one morning in December 2008, James had sex with his wife. Later that day, he was in pain and developed urinary urgency, which sent him back to the doctor. Once again, all of the tests were negative, and once again, the doctor concluded that James had pelvic floor syndrome.

James and his team of caregivers recently spoke about what happened next, his current treatment, and what men with similar symptoms might try to quell the pain and restore their quality of life. These are the caregivers:

- William C. DeWolf, M.D., a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and chief of urology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. He is particularly interested in prostate diseases and urinary tract cancers. He also serves on the editorial board of Harvard Medical School’s Annual Report on Prostate Diseases.

- Patricia Jenkyns, P.T., a physical therapist in the women’s health physical therapy program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She has worked mainly with women for the past 25 years, but increasingly, men have been seeking her expertise. She also teaches and trains others to provide pelvic floor physical therapy.

- Anurag K. Das, M.D., an assistant professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School and director of the Center for Neurourology and Continence at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. His areas of interest include incontinence, voiding dysfunction, pelvic prolapse in women, and prostate enlargement (BPH).

You said your symptoms returned in December 2008. What was the pain like?

JAMES: The pain was not as bad as it had been in the past, but I developed problems with urination. I saw Dr. DeWolf a couple of times because I was not able to urinate. I even went to the emergency room because I felt like I had to void, but I was not able to void. It was scary. They did an ultrasound and determined that I didn’t have anything in my bladder.

When your bladder was full, were you able to void?

JAMES: Later on, yes. But one day I was not able to urinate for 24 hours. On my way to see Dr. DeWolf, I stopped to go to the bathroom a few times. Things just suddenly opened up, and I was able to urinate. But Dr. DeWolf did a cystoscopy and a urodynamic study, and he didn’t find anything wrong. Again, he diagnosed pelvic floor syndrome and suggested that I try biofeedback.

What do you mean by pelvic floor syndrome? What’s the pelvic floor?

JENKYNS: The pelvic floor is the whole bony container that surrounds the organs in the pelvis. The pelvic floor muscles are the muscles involved with bowel, bladder, and sexual function. They include the levator ani, bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, and superficial transverse perineus. Pelvic floor syndrome means that these muscles aren’t working properly, causing problems with bowel, bladder, or sexual function.

It’s quite frightening when pain and other problems affect this part of the body because information about it isn’t readily available, and it’s not talked about openly. You’re not going to walk up to your next-door neighbor and say, “I’ve got this terrible pain in my scrotum.” So people often feel anxious, alone, and helpless.

What training do you have to work with the pelvic floor?

JENKYNS: I started specializing in pelvic floor dysfunction in 1984 with Elizabeth Noble, an Australian physical therapist who formed the Section on Women’s Health of the American Physical Therapy Association in 1977. Initially, I treated incontinence in postpartum and elderly women. Soon after that, pelvic floor pain problems were recognized in women, too. We learned through experience. Now I develop course work and provide training to others seeking a certificate of achievement in pelvic physical therapy.

Awareness and understanding of pelvic floor pain — as well as research on treating pain — have continued to grow. Women and men of all ages can be affected. In the last several years, the number of men seeing a physical therapist for pelvic floor work has increased dramatically.

What can you do to help someone like André?

JENKYNS: There are often telltale signs in a patient’s history that point to difficulties in relaxing the pelvic floor muscles — straining during urination or bowel movements, for example. In André’s case, the accumulation of stress, habitual pelvic floor muscle holding, and poor voiding habits led to an overactive pelvic floor, but it varies from person to person.

So I start by assessing the pelvic floor muscles. Can the patient contract them with ease? Can he relax them with ease? Can he do that consistently? When he bears down, do the pelvic floor muscles lengthen and relax? When he coughs, do those muscles contract with increased intra-abdominal pressure as they should? These functions are visually and manually assessed. In addition, the perineum, skin, superficial muscles, and the deeper levator ani muscles, innervated by the pudendal nerve, are felt for trigger points.

To see which trigger points cause muscle contraction?

JENKYNS: No, I’m looking to see whether touching specific points causes pain. First, the anal sphincter is examined for trigger points. Then, moving farther into the rectum, the levator ani muscles and the prostate are felt for painful trigger points. In André’s case, he had pain in his perineum, superficial muscles, and levator ani externally, as well as trigger-point pain in his anal sphincter and levator ani muscles rectally. He could not relax his pelvic floor muscles following a contraction or with bearing down. This is common in men with urinary frequency and urgency and pelvic pain.

How do you address the frequency and urgency issues?

JENKYNS: The patient is instructed to keep a bladder diary for three days in order to find out how often he voids and, if there is urgency, how much urgency. Many people don’t interpret the bladder’s signals correctly and void too frequently. As soon as they feel any bladder sensation, they think, “I must have to go to the bathroom.” Patients need to understand that if they never let the bladder fill completely, it can become sensitive to filling and will lose the capacity to hold urine over time. The average number of voids is five to seven times a day, or every two to four hours. The bladder should allow people to sleep through the night, although voiding once during the night is considered normal.

What is biofeedback? Where does that fit into the puzzle?

JENKYNS: Biofeedback enables a person to become more aware of their body’s signals. It is very useful for pelvic floor muscles because they are not visible. With increased awareness, patients can learn to correctly contract, relax, and coordinate these muscles so they work more effectively.

There are different types of biofeedback. Simple biofeedback can be done using your hand or a mirror. Pressure biofeedback can be used to strengthen weak muscles — patients can feel improvement when they squeeze an air-filled rectal sensor. I do not use pressure biofeedback for cases like André’s; he needed to concentrate on relaxation. Instead, I use a biofeedback unit with two “channels,” so that he can see what is happening in two different muscle groups: the pelvic floor muscles and the abdominal muscles. Ultimately, we want to coordinate the activity of these two muscle groups.

How do you do that?

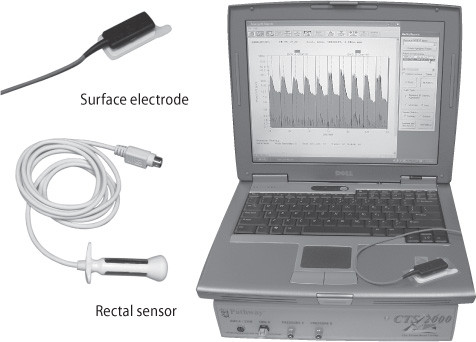

JENKYNS: One channel detects the activity of the anal sphincter and levator ani muscles through a sensor placed in the rectum. Surface electrodes from the second channel are placed on other parts of the body, such as the abdominal muscles. The sensor and electrodes detect the electrical activity of the muscles, and that information is filtered by the biofeedback equipment [see Figure 2]. It is displayed on a computer screen, with the data reported in microvolts. When squeezing the pelvic floor muscles, you should see an increase in activity on the screen. When relaxing, the activity should go down. If the patient cannot relax his pelvic floor muscles, the electrical activity stays high. With an overactive pelvic floor, the goal is to train the muscles to relax. When the patient relaxes the tight muscles, the electrical output decreases, and the patient can see a lower signal on the screen.

Figure 2: Biofeedback equipment

The surface electrode and rectal sensor plug in to a biofeedback machine (beneath the computer). Together, they detect and measure the electrical activity of muscles. Variations in muscle activity during contraction and relaxation are displayed on the computer screen. |

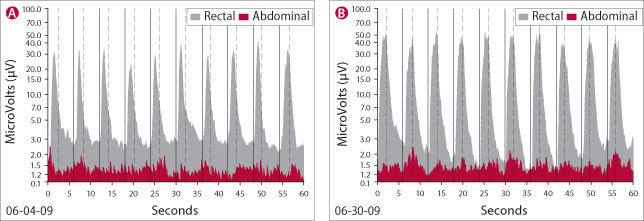

What do you ask the patient to do during biofeedback?

JENKYNS: I start by taking a 30-second baseline reading to see what the muscles look like during rest. Then I look at the patient’s ability to contract and relax those muscles. I’ll ask him to contract 10 times, with each contraction lasting for two seconds, followed by four seconds of relaxation [see Figure 3]. Then I’ll ask him to contract for five seconds and relax for 10 seconds. Based on the feedback, it becomes evident what the treatment plan needs to concentrate on. The patient needs to link what’s happening on the screen to what they feel in their muscles in order to receive the most benefit from biofeedback.

Figure 3: What biofeedback shows

The biofeedback machine produces graphs like these. Tall dark gray bands represent muscle activity in the rectum; low red bands show abdominal muscle activity. The high peaks occur during muscle contractions; valleys occur when muscles relax. Both graph A and B show a series of two-second contractions followed by four-second periods of relaxation. Notice how valleys in graph B deepen as the patient becomes more aware of the muscles’ activity. The abdominal muscles are better coordinated with the rectal muscles in graph B — peaks and valleys in both red and gray bands happen at the same time. Practice helps. The session illustrated in graph B took place nearly a month after the session shown in graph A. |

And then you try to have the patient reproduce that voluntarily?

JENKYNS: Exactly, but not just reproduce it once. It’s essential for patients to reproduce it consistently. That is the key. Habits die hard, so it’s important for the patient to practice repeatedly what he’s learned in the treatment sessions. Many people with pelvic pain, urinary frequency, and urgency habitually contract the pelvic floor muscles. A helpful exercise is to tune in to those muscles five times a day and voluntarily release the tension in them. Breathing exercises and meditation can help decrease the electrical activity.

Is there medical literature that supports the use of biofeedback for patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome?

JENKYNS: There is evidence linking pelvic floor muscle spasm with pelvic pain, urinary frequency, and urgency, and some research on the use of biofeedback in men with pelvic pain. The studies show that it is a safe and effective treatment that provides pain relief. We also have anecdotal evidence that it works, but larger randomized clinical trials need to be done to confirm this. [See “Biofeedback for CPPS.”]

Biofeedback for CPPSClemens JQ, Nadler RB, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Biofeedback, Pelvic Floor Reeducation, and Bladder Training for Male Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Urology 2000;56:951–55. PMID: 11113739. Cornel EB, van Haarst EP, Schaarsberg RW, Geels J. The Effect of Biofeedback Physical Therapy in Men with Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome Type III. European Urology 2005;47:607–11. PMID: 15826751. Ye ZQ, Cai D, Lan RZ, et al. Biofeedback Therapy for Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Asian Journal of Andrology 2003;5:155–58. PMID: 12778328. |

Do you think that habitual contraction of the pelvic floor muscles was responsible for André’s penile and testicular pain and his urinary difficulties?

JENKYNS: Yes. It is likely that habitual contraction of the pelvic floor muscles led to pelvic floor muscle spasms that caused the pain and urinary difficulties. In terms of urinary difficulties, the pelvic floor muscles need to relax for the bladder to empty. Biofeedback can be used in a variety of positions to promote relaxation. André found that when he lies down and completely relaxes by using diaphragmatic breathing and meditation, he can relax his pelvic floor muscles. He still has difficulty relaxing the muscles while standing and trying to urinate, but he continues to practice. Sometimes, it may be helpful for men to sit down to urinate so that they can better relax those muscles.

DAS: That’s actually an issue in women. A lot of women believe that toilet seats are dirty, so they don’t want to sit on them to urinate. Instead they hover over the toilet. But you can’t relax the pelvic floor sufficiently when you hover. We try to get them to sit or squat — squatting is okay, but you can’t hover.

I’ve seen patients whose pelvic floor muscles are so tight that they even walk awkwardly. You can literally see the tension. Changing that is difficult because it’s probably built up over many years. You can’t just get rid of it.

JENKYNS: That’s why I think André’s symptoms have changed over the years. The tension is accumulating and getting worse and worse.

Do you think the testicular pain he experienced back in 1996 is part of the same process that is going on now?

JENKYNS: I think it was an early sign. He’s had several flare-ups, and they seem to occur when there’s more tension and stress in his life. He manages to let go of some of the tension for a while, but then it flares up again. It’s an up-and-down process, and over time, the tension builds.

JAMES: It’s definitely stress-related. One day, I heard some upsetting news from a family member. After that, I felt as if there was a foreign object in my rectum. I was convinced that I suddenly developed a rectal tumor. I couldn’t even walk because of the pain. I went to my primary care physician, who sent me to have a sigmoidoscopy. [See “What’s a sigmoidoscopy?”] That didn’t show anything, and eventually the discomfort went away. But now when I have a flare-up of my pelvic floor syndrome, I sometimes experience pain in my rectum.

JENKYNS: I also ask André and the other men I work with to do some lower-extremity stretching to work the hip joints and all of the related muscles.

What’s a sigmoidoscopy?During this test, doctors examine the inside of the rectum and the last section of the large intestine — the sigmoid colon — using a flexible viewing tube inserted through the anus. Doctors use a similar device during a colonoscopy, but they examine the entire length of the large intestine. |

And that helps?

JENKYNS: Yes, it can ease the tension.

JAMES: It helps tremendously. I can’t overstate the value of stretching. It really helps relax the pelvic floor. After stretching, I can urinate much more easily.

What is myofascial release? Is it done internally? Externally?

JENKYNS: “Myo” means muscle and “fascia” refers to the elastic connective tissue that surrounds and supports the muscles, organs, bones, nerves, and blood vessels in the body. Stress, trauma, chronic inflammation, overuse, and poor posture can cause the fascia to thicken and tighten. So, in general, myofascial release is a type of massage that focuses on desensitizing the nervous system, easing tension, and stretching and lengthening muscles and fascia to relieve pain.

For patients like André, we focus on the pelvic floor muscles and surrounding soft tissues, doing both external and internal work.

With massage?

JENKYNS: Yes. There are different types of massage, also called soft tissue mobilization. Skin rolling is one technique in which the skin is lifted between the thumb and fingers and gently rolled back and forth to release any restrictions between the skin and underlying tissues. In addition, pressure is repeatedly applied along the entire length of muscle or over taut bands of tissue. The amount of pressure varies and depends on the patient’s response, but the overall goal is to lessen the pain and quiet down the nervous system.

There is only minimal research on myofascial release for pelvic pain in men, but the few studies that have been done have found it beneficial. In the clinic, I’ve seen patients improve with myofascial release, especially in combination with biofeedback, stretching exercises, and bladder retraining.

What about prostatic massage?

DAS: That was a therapy for prostatitis in the early 20th century. It was later used to help drain fluids from the prostate so that they could be checked for infection and to help open any blocked prostate ducts — at least in theory. With little else to offer, some doctors are trying this with patients, and some patients do seem to improve.

My theory is that the prostate massage has nothing to do with the prostate. Rather, you are stretching the external sphincter, the rectal sphincter, and other muscles, and that’s what helps the patient. I don’t think the improvement some patients experience has anything to do with the massage of the prostate itself.

What do you do on a daily basis, André, to keep the pain and urinary problems at bay?

JAMES: Well, in addition to my periodic biofeedback and myofascial trigger point release sessions, I try to stretch. I’m still on lorazepam. And I try to avoid stress, because stress is clearly a trigger for me.

Dr. Das, what role have you played in André’s care? How do you treat patients in a similar situation?

DAS: I see a lot of patients with frequency and urgency complaints as well as patients who can’t completely void. I tend to see people at the extremes, including patients who can’t “go” at all. And I see patients who haven’t had success with biofeedback or pelvic floor work. In such cases, I treat them with direct nerve stimulation. This involves electrically stimulating the sacral nerve and sacral nerve root.

To do this, a small needle is placed in the lower back at the third sacral nerve root. [The sacrum is a wedge-shaped set of bones near the base of the spine; nerves travel through gaps in these bones.] Then a wire is placed through the needle and attached to a small electrical stimulator after it’s taped securely to the skin. The patient can carry the stimulator, which is the size of a cell phone, on a belt or in a pocket. He or she uses it for a week, keeping track of voiding habits. If the patient feels that his or her symptoms have improved significantly, and we see improvement of 50% of more objectively, we consider permanently implanting the device.

And you are doing this in men?

DAS: Yes. About 10% of our patients with these severe problems are men.

What are the specific indications for implanting a nerve stimulator?

DAS: The three indications from the FDA are frequency and urgency — patients who are going about 20 times a day or almost every hour; urge incontinence — patients who can’t make it to the bathroom; and retention — patients who can’t go at all.

And the reason they went into retention?

DAS: The theory is that they are not relaxing their pelvic floor muscles. The first thing that occurs when you try to void is that the pelvic floor should relax. If you can’t relax the pelvic floor, you can’t start voiding.

What gave you the wisdom to send this patient to see a physical therapist for biofeedback, Dr. DeWolf?

DeWOLF: My interest in this started when I was a resident and heard a talk by a famous urologist, Dr. Frank Hinman, about psychogenic retention in pediatric patients. These kids seemed to have complete urinary obstruction, but tests showed nothing was wrong with them. They were eventually cured with hypnosis. Hinman thought that there was a lack of coordination between the external sphincter and the bladder. I filed that idea away.

Then I started to see some patients with what the NIH called type III prostatitis, which is pelvic pain without infection. Urinary symptoms may or may not be present. Applying what I had learned from Dr. Hinman in the 1970s, I started developing a hypothesis that these patients have a pelvic floor that isn’t coordinated with how the bladder works. The pelvic floor becomes impenetrable. As Dr. Das just said, the first act of voiding is relaxation of the pelvic floor. If you can’t relax it, then the bladder has a hard time releasing urine. That’s what I mean by pelvic floor syndrome.

There are several signs that tell me I’m dealing with a patient who has a pelvic floor problem. First of all, the patient will likely be on the young side — in my experience, most patients are between 35 and 50 years old when the problem starts. Second, there will be nothing wrong with the patient’s physical evaluation. He can void, and he doesn’t get up several times a night to urinate. He doesn’t have a urinary tract infection. But because the pelvic floor muscles are tight, he is in pain — and the pain makes the pelvic floor even more resistant to relaxation.

So here’s what happens: the pelvic floor tightens up, but the bladder tries to push urine through it. In doing so, it generates high pressures and — this is an important point — it puts very high pressure on the prostate, because the bladder is trying to force urine through the urethral sphincter. Remember, the urethra runs through the prostate. Done repetitively, this can irritate the prostate, causing pain in anything attached or related to the prostate — the testicles, the penis, which is attached to the urethra, the rectum, the suprapubic area, or the bladder. The bladder registers that as urgency, and it becomes inflamed. I used to prescribe muscle relaxants to patients with pelvic floor muscle tightness.

Was there scientific evidence to support the use of muscle relaxants?

DeWOLF: Frank Hinman’s original work dealt with hypnosis to relax the muscles. Not knowing what else to do, I tried the pharmacological equivalent of hypnosis. But now I refer my patients for biofeedback and myofascial trigger point release. I tell them that it might take awhile to reverse the problem, but I think it’s the only way to attack it. Patients have to learn how to relax the pelvic floor. If they lessen tension in the pelvic floor, the pain dissipates and the bladder can empty normally.

Any concluding comments?

DeWOLF: It amazes me that there are 1.8 million men in the United States who have CPPS, according to the NIH, but it’s so poorly understood. There’s nothing obviously wrong, nothing to fix, so doctors just refer these patients to someone else. I now see at least one patient a week with this condition, and he’s usually been to four or five other physicians before me. I think it’s critical that we learn more about this condition and study the effectiveness of different treatments so that we can provide the best possible care for our patients — and help alleviate their suffering.

Originally published October 2009; last reviewed Feb. 23, 2011

About the Author

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.