Gastroparesis: A slow-emptying stomach can cause nausea and vomiting

If you have a daily commute, a backup of traffic or road work may delay you, but you'll eventually reach your destination. Gastroparesis, a digestive condition, can be imagined as a slowed commute through the stomach. But the delay involved can cause uncomfortable symptoms, and may have other health consequences that can affect nutrition and your quality of life. Although gastroparesis affects millions of people worldwide, many people are much more familiar with other gut problems, such as acid reflux and gallstones, that can cause similar symptoms.

What is gastroparesis?

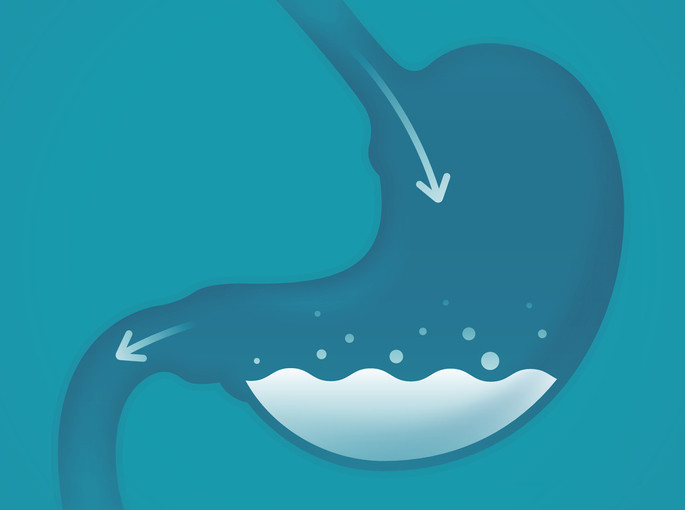

Gastroparesis is a condition that causes delay in the emptying of the stomach. When you swallow food, it travels through your mouth and into a long tube called the esophagus before entering your stomach. Your stomach serves two separate functions: The first is to relax to accommodate food and liquid until you feel full. The second is to churn the food and liquid into a slurry that then passes into your small intestine to be digested. When either function is disturbed, slower-than-normal emptying occurs.

What are the symptoms of gastroparesis?

Nausea and vomiting are two of the most common symptoms of gastroparesis, most likely stemming from the sluggish emptying of the stomach. Typically, these symptoms occur toward the end of meals or soon after meals are finished. A third common symptom is abdominal pain caused by a combination of motor nerve and sensory nerve dysfunction. When motor nerves aren't working properly, food and liquid can be detained in the stomach. When sensory nerves aren't working well, signals between the gut and the brain are not communicated effectively, which can cause pain, nausea, and vomiting.

A growing body of evidence suggests that gastroparesis overlaps with a disorder of gut-brain interaction called functional dyspepsia, which is recurring indigestion that has no apparent cause. Other health problems can cause similar symptoms as gastroparesis, such as gastric outlet obstruction and cyclic vomiting syndrome, or even conditions beyond the gut, such as glandular disorders. So it's important to discuss any symptoms that are bothering you with your doctor to get the correct diagnosis.

Who is more likely to experience gastroparesis?

Many misconceptions exist about the typical person with gastroparesis. For example, it's not true that people must have diabetes to have gastroparesis: only 25% of people with gastroparesis have diabetes. Most commonly, no clear cause for gastroparesis can be found among people who have the condition.

Additionally, people are more likely to experience gastroparesis if they

- take certain medicines, such as opiate pain medications and some medications for diabetes

- have had surgeries, radiation, or connective tissue disorders that affect the function of the nerves of the gut

- are female, because women are several times more likely than men to have gastroparesis.

Thus far, there is limited information on health disparities among people with gastroparesis, although one study shows that diabetes is more likely to be the cause of gastroparesis among Black and Hispanic patients than white patients. It's not yet clear why, although socioeconomic inequities that affect health outcomes may be a factor (as is true for many other conditions).

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosing gastroparesis and deciding on the best treatment strategy requires a careful patient history, blood tests, imaging tests, and sometimes endoscopy. Usually, people first discuss their symptoms with a primary care doctor who can rule out some possible causes and refer them to a specialist to discuss next steps, such as imaging or endoscopy, if necessary.

A common imaging test used in the US is called a gastric emptying scan, which takes four to five hours. The person having the test eats a standardized meal, such as an egg sandwich, that contains safe levels of medical-grade radiation. At certain intervals, images are taken to see how much of the meal remains in the stomach. During normal digestion, about 90% of the stomach is emptied within four hours and 10% is left behind; more than this amount remaining meets a key criterion for gastroparesis.

It's worth noting that the exact amount of stomach emptying in four hours may fluctuate and may be influenced by other health factors, such as uncontrolled blood sugar, or certain medications, particularly opiate pain medicines.

How is gastroparesis treated?

The main goal of treatment is to address the symptom that bothers you the most. Depending on your diagnosis and symptoms, treatment might involve one or more of the following:

- Medications. Erythromycin and metoclopramide speed up emptying the stomach. A newer medicine called prucalopride may have the same effect. Other medications, particularly for people who are finding pain and nausea more problematic, target disordered gut-brain interaction using neuromodulators, such as older forms of antidepressants and neuropathy medications. These medicines may improve sensation of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Procedures and surgeries. A gastroenterologist may suggest different endoscopy techniques that improve stomach emptying by disrupting a valve between the stomach and the small intestine called the pylorus. One approach, called a per-oral pyloroplasty, does not require surgery. A surgical approach called laparoscopic pyloroplasty reshapes the muscle of the valve between the stomach and small intestine to help the stomach empty more quickly. Less often, surgically implanting a gastric stimulator to help improve the signaling between gut and brain may be considered.

If you have gastroparesis, be sure to discuss all these treatment options to see which one is best for you.

Follow me on Twitter @Chris_Velez_MD

About the Author

Christopher D. Vélez, MD, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.