“Just in case” heart tests can do more harm than good

Here’s an important equation that all of us—doctors included—should know about health care, but don’t:

More ≠ Better

“More does not equal Better” applies to diagnostic procedures, screening tests meant to identify problems before they appear, medications, dietary supplements, and just about every aspect of medicine.

That scenario is spelled out in alarming detail in the Archives of Internal Medicine. Clinicians at the Cleveland Clinic describe the case of a 52-year-old woman who went to her community hospital because she had been having chest pain for two days. She wasn’t having symptoms of a heart attack, such as shortness of breath, unexplained nausea, or a cold sweat, and her electrocardiogram and other tests were fine. The woman’s doctors concluded that her chest pain was probably due to a muscle she had pulled or strained during her recently begun exercise program to lose weight.

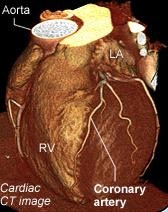

To “reassure her” that she wasn’t having a heart attack, the emergency department team recommended she have a CT scan of her heart. This noninvasive procedure can spot narrowings in coronary arteries and other problems that can interfere with blood flow to the heart. When it showed a suspicious area in her left anterior descending artery (a key artery nourishing the heart), she underwent a coronary angiogram. This involves inserting a thin wire called a catheter into a blood vessel in the groin and deftly maneuvering it into the heart. Once in place, equipment on the catheter is used to make pictures of blood flow through the coronary arteries.

During the angiogram, the woman’s aorta was torn. Emergency bypass surgery was needed to fix this tear. The bypass graft failed, and she had several wire-mesh stents implanted to hold open the graft. A blood clot formed inside one of the stents, causing a heart attack and complete heart failure. She ultimately needed a heart transplant.

Such an unfortunate chain of events is rare. But it highlights the fact that things can, and do, go wrong in medicine—as in every other aspect of life and business. No test, no procedure, no drug or dietary supplement is 100% safe.

Readers of the Harvard Heart Letter often write asking if they should have an exercise stress test or a coronary calcium test or a scan of their carotid arteries “just in case,” even though they feel fine and are in generally good health. In theory, such information could warn about an impending heart attack or stroke. The answer from cardiologists on the newsletter’s editorial board is a resounding “No.” Why? Because the chances of causing harm—physical, emotional, or financial—often far exceed the limited diagnostic information and advice for management the test provides.

Tests and procedures are justified when there are solid, evidence-based reasons for performing them, when the anticipated benefits exceed the likelihood of risk, and when their results will clearly change how a person’s care is managed. Reassurance and “just in case” don’t fill the bill.

About the Author

Patrick J. Skerrett, Former Executive Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.