Opioid addiction and overdoses are increasingly harming Black communities

Rising opioid deaths in Black communities can be linked to health disparities.

The opioid epidemic caused half a million deaths between 1999 and 2019. But far from abating, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused it to dramatically spike, with more people dying of opioids last year than in any prior year. Yet the contours of the crisis have changed.

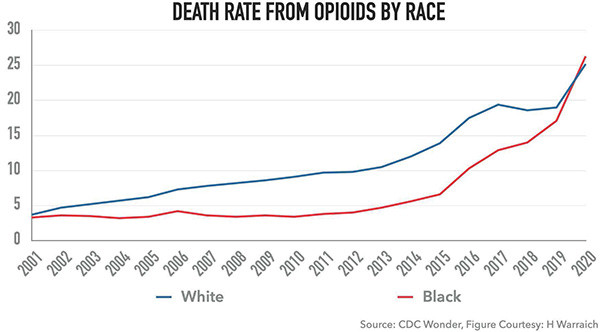

The opioid epidemic has traditionally been thought of as one that mostly affects white Americans, and largely in rural areas. This was partly intentional, since pharmaceutical companies targeted these areas to avoid the glare of law enforcement agencies. Another reason why white Americans were more likely to be addicted to opioids was because Black people were much less likely to be prescribed opioids for pain control, even when medically indicated in emergent conditions. However, new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that the reason the opioid epidemic is now growing at breakneck pace is because of its rapid infiltration into Black communities.

New research highlights more Black Americans are dying of overdoses

A recently published report from the CDC provides a stark view of how the opioid epidemic is increasingly ensnaring Black people in its vise. In 2020, opioid overdoses rose 30% compared to 2019, leading to 91,799 deaths. However, the increase was not uniformly noted. The death rate among Black Americans increased by 44%, the greatest increase among all racial and ethnic groups, and double that for white Americans.

Young Black people between the ages of 15 and 24 saw an 86% increase in opioid death rate. In fact, according to my analysis of the CDC WONDER database, in 2020 Black Americans had a greater death rate from opioids than white Americans for the first time during the entire two-decade history of the opioid crisis.

|

In 2020, for the first time during the entire opioid epidemic, the death rate from opioid overdoses was greater for Black Americans than white Americans, in large part due to the surge in illicit fentanyl. |

Opioid deaths add to the systemic burdens on Black communities

One of the Black victims of opioid addiction was George Floyd. "Our story, it's a classic story of how many people get addicted to opioids," Courteney Ross, Floyd's girlfriend, testified during the trial in Minneapolis. "We both struggled from chronic pain. Mine was in my neck and his was in his back." In fact, opioids could very well have killed George Floyd prior to his murder in May 2020; he was hospitalized for an opioid overdose in March of that year.

At a time when Black communities are suffering disproportionately from the COVID-19 pandemic and police brutality, they are also being doubly battered by the ongoing opioid epidemic. The opioid epidemic is compounding the existing inequities in the United States: the CDC study shows that the areas with the greatest degree of income inequality had double the death rate from opioids among Black Americans compared to areas with the least income inequality.

What is causing this increase in opioid deaths?

Why has opioid misuse surged among Black Americans during the pandemic? A key culprit is the rise of fentanyl, an opioid that is far more lethal than others, which has overrun America through rampant export from overseas. Research my team published in JAMA showed that the pandemic was associated with a drop in medical prescriptions for opioids, with subsequent work suggesting this only occurred for new users rather than for those previously prescribed opioids.

This reduction occurred because of the closures of clinics and pharmacies, yet abrupt stoppage of prescription opioids can be dangerous. A recent study showed that patients whose opioids are suddenly stopped have a higher risk of suicide, since it may induce them to turn to illicit opioids like heroin and fentanyl.

Unequal access to addiction treatment compounds the problem

A major reason for the growing racial divide in opioids is based on who actually gets access to substance use treatment. While only 14% of those who died of opioids received treatment for substance misuse overall, among Black Americans the proportion was 8%, the lowest of all groups. Treatment services for opioid use disorder were severely hit by the pandemic, leading to abrupt closures of services that were serving as lifelines for many users.

Policy changes and better access to pain treatments could turn the tide

Simply making resources available for substance use and mental health are unlikely to move the needle by themselves. Opioid death rates among Black Americans were highest in areas with the greatest availability of addiction and mental health treatment centers. What is really needed is a broad public health campaign and outreach to Black communities highlighting the dangers of opioid misuse, providing community-based resources for harm reduction and addiction treatment, and reducing the stigma associated with opioid misuse and seeking treatment.

The War on Drugs was revealed by one of its originators as being racist in nature. The last thing we need is for us to again criminalize the use and misuse of these drugs, which could put already vulnerable Black communities — disproportionately affected by opioids and overzealous law enforcement — in double jeopardy. Ridding the streets of fentanyl through more stringent scrutiny is an important part of the National Drug Control Strategy released earlier in the year by the Biden administration, but care must also be taken to ensure that Black Americans who experience pain, or who have been prescribed chronic opioids, are not left to suffer.

Interdisciplinary pain treatments that are evidence-based can provide significant relief for people in chronic pain, and an important goal needs to be ensuring that all patients, particularly those who are already suffering disproportionately, receive access to these therapies. Yet to ensure that Black people are both able to get appropriate pain relief, and also do not suffer disproportionately from the opioid epidemic, we need to ensure that barriers to treatment are eliminated once and for all.

About the Author

Haider Warraich, MD, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.