Prostate cancer lives as it is born: slow-growing and benign or fast-growing and dangerous

This year, more than 238,000 American men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer. In most cases, the cancer consists of small knots of abnormal cells growing slowly in the walnut-sized prostate gland. In many men, the cancer cells grow so slowly that they never break free of the gland, spread to distant sites, and pose a serious risk to health and longevity.

Evidence is growing that early treatment with surgery or radiation prevents relatively few men from ultimately dying from prostate cancer, while leaving many with urinary or erectile problems and other side effects. As a result, more men may be willing to consider a strategy called active surveillance, in which doctors monitor low-risk cancers closely and consider treatment only when the disease appears to make threatening moves toward growing and spreading.

This week, a study by Harvard researchers found that the aggressiveness of prostate cancer at diagnosis appears to remain stable over time for most men. If that’s true, then prompt treatment can be reserved for the cancers most likely to pose a threat, whereas men can reasonably choose to watch and wait in other cases.

“If you have chosen active surveillance, then this could possibly make you feel more confident in your decision,” says Kathryn L. Penney, Sc.D., instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School and the lead author of a report published today in the journal Cancer Research.

Cancer lethality set early

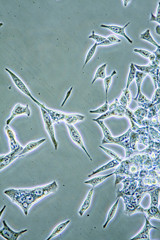

The study looked for changes in cancer aggressiveness in men diagnosed with prostate cancer from 1982 to 2004. All of the men had their prostates removed after diagnosis, and biopsy samples were taken from the glands. The Harvard team reexamined the samples and graded them using a tool called the Gleason score, which assigns a number from 2 to 10 based on how abnormal the cells look under a microscope. High-scoring or “high-grade cancers” tend to be the most lethal.

Over the study period, fewer and fewer men were diagnosed with advanced, late-stage prostate cancers that had spread beyond the prostate gland. This reflected the growing use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing to diagnose prostate cancers earlier and earlier. In contrast, the proportion of high-grade cancers, as measured by the Gleason score, remained relatively stable rather than gradually becoming more aggressive. Previous studies have seen a similar pattern.

“It’s a very interesting study that confirms what previous studies have found,” says Dr. Marc B. Garnick, a prostate cancer specialist at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center who was not involved in the study. “There may be rare exceptions, but in the vast majority the cancer is born with a particular Gleason score.”

That means most prostate cancers that look to be slow growing at diagnosis could stay that way long enough that the man is likely to die from another cause before the cancer spreads beyond the prostate. “The ones that are low-grade and indolent are unlikely to cause problems in a man’s lifetime,” says Dr. Garnick, editor of the Annual Report on Prostate Diseases, from Harvard Medical School. On the other hand, he adds, most high-grade prostate cancers are also born that way and will behave aggressively.

Gleason grade is one of the best predictors of prostate cancer death. “Men with low-grade disease are much less likely to die from prostate cancer than men with high-grade cancers,” says Penney. She cautions, though, that the study looked at men as a group, and in this population the Gleason grade appeared to be fairly stable. “You might see progression in an individual, but we think that it’s uncommon,” she says. “We just can’t rule out this possibility in our study.”

How active surveillance works

The Gleason score is just one way that doctors monitor prostate cancer during active surveillance. They also do periodic follow-up biopsies and measure PSA levels, which may rise if cancer starts to spread in the prostate. Doctors may recommend treatment sooner if PSA begins to rise quickly or if a follow up biopsy reveals a higher Gleason score or more widespread cancer within the prostate. It’s an inexact science that depends on a doctor’s skill and experience and a man’s willingness to wait for signs that a cancer poses a clear threat before opting for treatment and its potential for side effects.

Penney says she and her Harvard colleagues are among the many scientists now searching for better ways to predict which prostate cancers are likely to be lethal and which can be monitored and not treated. The answer may be found in genetic changes in prostate cancer cells that signal a higher threat. But finding a better way to predict which prostate cancers are likely to turn lethal is far from guaranteed.

“Some [researchers] believe it’s not possible,” Penney says. “After the cancer is diagnosed, so many things can change in unknown ways.” Diet, exercise, and other lifestyle factors, for example, could affect whether low-risk prostate cancers become more aggressive or threatening over time.

About the Author

Daniel Pendick, Former Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.