PSA screening for prostate cancer: a doctor’s perspective

Yesterday’s announcement that men should not get routine PSA tests to check for hidden prostate cancer is sure to spark controversy for months to come. I believe that the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) made the right decision, and I commend how it came to its conclusion.

On the surface, rejecting the use of a simple blood test that can detect cancer in its early and still-treatable stage sounds foolish. Cynics have been saying it is the handiwork of a group concerned more about health-care rationing and cutting costs than about health. The decision is wise, not foolish, and will improve men’s health, not harm it.

The word “cancer” usually brings to mind images of a fast-growing cluster of cells that, without aggressive treatment, will invade other parts of the body, damage health, and potentially kill. That certainly describes many cancers. But not most prostate cancers. Most of the time, prostate cancer is sloth-like. It tends to grow slowly and remain confined to the prostate gland, with many men never knowing during their entire lives that a cancer was present. These slow-growing prostate cancers cause no symptoms and never threaten health or longevity. That means many men with prostate “cancer” never need treatment.

Before the advent of PSA testing in the 1990s, some men learned they had prostate cancer because of symptoms such as trouble urinating or persistent pain in the pelvic region. Others were diagnosed when a doctor performed a rectal exam and felt suspicious bumps on the prostate. These digital rectal exams remain an important part of a man’s physical exam since they can spot what are called clinically detectable cancers, for which treatment may still be helpful.

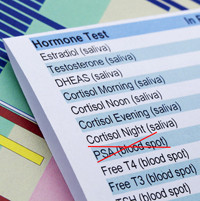

A high PSA level is one way to signal other tests, such as a biopsy, that can tell if cancer cells are present. Unfortunately, it can’t tell the difference between a dangerous cancer that requires treatment and one that doesn’t. For that reason, most men who have an elevated PSA and a biopsy that shows cancer cells in the prostate choose to have surgery or radiation therapy. Many of them don’t need treatment, though, and live with side effects such as impotence, incontinence, and rectal bleeding for naught.

Evidence-based decision

The USPSTF is made up of volunteers from a variety of fields, including internal medicine, family medicine, behavioral health, and preventive medicine. None have financial interests in tests or treatments.

The task force based its recommendation about PSA screening on many studies, but the main focus was on two key randomized clinical trials, the gold standard of medical evidence. One, conducted in Europe, had 11 years of follow up, which is extraordinarily long for clinical trials. It compared the health outcomes of men who were offered PSA screening with the outcomes of men who were not offered the PSA test. The panel looked at clear-cut, measureable endpoints such as death, death from prostate cancer, and rates of infection, impotence, incontinence, and other downsides of prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment.

In the outcome that mattered the most—death—there was no difference in overall mortality among men who had the PSA test and those who didn’t, though there was a small decrease in prostate cancer deaths over the 11 years of follow in the screened population. The researchers calculated that 1,410 men would need to be tested, and 48 additional cases of prostate cancer would need to be treated, to prevent one death from prostate cancer. PSA-based screening slightly reduced the rate of death from prostate cancer, “but was associated with a high risk of overdiagnosis,” the authors concluded.

The second trial was the U.S.-based Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Screening Trial. After 13 years of follow-up, the cumulative death rate from prostate cancer was 3.7 deaths per 10,000 person years in the PSA screening group and 3.4 deaths per 10,000 person-years in the control group. Again, no difference. In contrast to the European study, and in keeping with the practice of medicine as currently practiced here in the U.S., there was no difference in the death rate from prostate cancer in the screened group compared to controls.

All trials have flaws, and advocates of PSA screening say that these flaws undermine the USPSTF recommendation. Had these flaws not been present, they say, the results would have supported the benefits of screening. This charge has not been borne out. In addition, the critics base their arguments on results from just two of the countries in the European study, which had better results than the other five.

Moving ahead

For years, I have been counseling my patients about the uncertainties of routine PSA testing, and more importantly, the uncertainties around treating certain prostate cancers once they’ve been detected.

Many of my patients have chosen to be treated for their prostate cancer. These decisions were made before we know what we do now about PSA testing and subsequent treatment for PSA-detected prostate cancer.

Going forward, making decisions about having the PSA test in the first place to choosing whether or not to start treatment immediately if cancer is diagnosed will have a very different tone, based upon the approach now recommended by the USPSTF. For my patients who will continue to want the test, I will make sure they know that while PSA testing can detect prostate cancer early, many of the cancers it detects will do no harm.

New tests under development may someday be able to tell a dangerous prostate cancer from an indolent one. In the meantime, as I explained in a recent Scientific American article, the practice of medicine should reflect what current studies show, and our decisions should be based upon evidence and not just our beliefs.

About the Author

Marc B. Garnick, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Medical School Annual Report on Prostate Diseases; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.