Recipe for health: cheap, nutritious beans

I’ve been thinking about beans this week for a few reasons. One is an upcoming trip with my family to Nicaragua, where we will probably eat beans three times a day. Another is a paper in this week’s Archives of Internal Medicine showing that adding more beans to the diet can help people with diabetes better control their blood sugar.

Beans, the butt of countless flatulence jokes, are often written off as food for poor people, or cheap substitutes for meat. Given what beans can do for health, they should be seen as food fit for royalty—or at least for anyone wanting to get healthy or stay that way.

Legumes at any meal

The beans I’m talking about here are what botanists call legumes. Some people call them “pulses.” There are many types: adzuki beans, black beans, black-eyed peas, broad beans (fava beans), calico beans, cannellini beans, garbanzo beans (also called chickpeas), kidney beans, lentils, lima beans, mung beans, navy beans, peanuts, pinto beans, soybeans (also called edamame), and others.

Legumes are a terrific food. They are an excellent source of protein. They are low in fat. They are nutrient dense, meaning they deliver plenty of vitamins, minerals, and other healthful nutrients relative to calories. They provide plenty of soluble and insoluble fiber.

You can eat beans at any meal. Gallopinto (based on black beans and white rice) is a traditional breakfast dish in Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Bean burgers or falafel (deep-fried patties made from ground chickpeas, fava beans, or both) make a decent lunch. You can use beans in salads and stews, or build main dishes around them. A few recipes from a new cookbook, Bean by Bean, are available here. Many others are available courtesy of the California Dry Bean Advisory Board.

Beans and health

The article that caught my eye in Archives of Internal Medicine reported the results of a 12-week bean trial. It compared the effects of a diet enriched with legumes (one cup a day) to one enriched with whole wheat foods among people with type 2 diabetes. Both diets lowered blood sugar, though the bean-rich diet did it a little better. Both diets also lowered levels of harmful LDL (“bad” cholesterol) and triglycerides, the most abundant fat-carrying particle in the bloodstream. They also slightly lowered blood pressure.

These findings are in line with a growing body of evidence on the health benefits of eating beans. They’ve been linked to reduced risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and colon and other cancers, as well as improved weight control. Last summer, a special issue of the British Journal of Nutrition was devoted to the various health benefits of legumes.

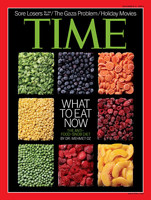

With all of this going for beans, I was surprised that they were omitted from the cover of this week’s Time magazine illustrating what we “should” be eating. Beans are every bit as colorful as the fruits and vegetables pictured, and definitely deserve a place at the table.

The gas tax?

Many people shun beans because of their gaseous aftereffects. Human digestive enzymes can’t break down the fiber and short chains of sugar molecules known as oligosaccharides in beans. But the billions of bacteria living in the gut can digest them, often creating gas in the process.

Here are some tips from the Harvard Heart Letter to help you turn off the gas:

Soak your beans. Soaking beans can get rid of a good portion of the indigestible oligosaccharides. Soak beans for 12 to 24 hours in a few quarts of water, pour off the soaking water, rinse, add clean water, and cook.

Choose wisely. Some beans seem to create less gas than others. These include adzuki and mung beans, lentils, and black-eyed, pigeon, and split peas. Heavy-duty gas formers include lima, pinto, navy, and whole soy beans.

Start slow. Let your body get used to fiber and oligosaccharides by having a small serving once or twice a week. Then gradually increase your intake, either by taking larger servings or eating beans more frequently.

Put your teeth to work. The more thoroughly you chew beans, the more you expose them to natural oligosaccharide-digesting enzymes in your saliva.

Gas-busters to the rescue. An enzyme called alpha-galactosidase breaks down some gas-producing oligosaccharides. The original product, Beano, has since been joined by others with names like Bean Relief, Bean-zyme, and plain old alpha-galactosidase. Taking a tablet before eating beans can reduce gas production.

About the Author

Patrick J. Skerrett, Former Executive Editor, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.