Harvard Health Blog

Starting an osteoporosis drug? Here’s what you need to know

ARCHIVED CONTENT: As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date each article was posted or last reviewed. No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

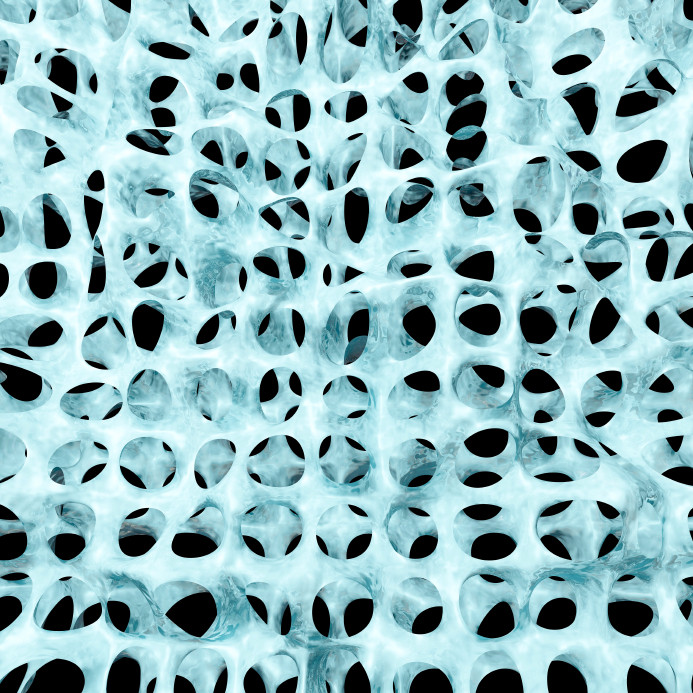

Human life expectancy has doubled since 1800. It is a tremendous success story for humankind — but each success brings more challenges to overcome. Because many people are living longer these days, one of the biggest responsibilities of modern medicine is to provide care and treatment for those diseases that become more common with increasing age. One of those diseases is osteoporosis, a thinning and weakening of the bones, which means they break more easily. They can break easily. Osteoporosis can compromise quality of life if it leads to a fracture, and complications of fracture can even lead to death.

Osteoporosis: The “silent enemy”

Osteoporosis is most common in older people, especially (but not only) in women. In many cases, it is first revealed by a sudden fracture — and by the time that happens, it is too late to go back and prevent this dreadful event, which can lead to many complications. According to an article published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, each year Americans suffer from 1.5 million osteoporotic fractures, resulting in more than 432,000 hospital admissions, almost 2.5 million medical office visits, and about 180,000 nursing home admissions. Medicare currently pays for approximately 80% of these fractures, with hip fractures accounting for 72% of the total cost. And because people are living longer (and are therefore more likely to get osteoporosis), the cost of osteoporosis care is expected to rise to $25.3 billion by 2025.

Why not more treatment for osteoporosis?

Despite the availability of cost-effective and well-tolerated treatments that can reduce fracture risk, only 23% of women ages 67 or older who have an osteoporosis-related fracture receive either a bone mineral density test or a prescription for an osteoporosis drug in the six months after the fracture. There are also many available options for preventing and treating osteoporosis before a woman ever experiences a fracture.

Why are so many people, especially women, not receiving osteoporosis treatment? In part because these treatments have faced multiple controversies. Many women have questions when they’re offered preventive treatment, such as: Can calcium supplements increase the risk of heart disease? What will happen to my jawbone if I take this medication? Will this pill give me esophageal cancer? And if I’m not hurting, why do I need treatment at all?

Fortunately, we have some good data to help answer these questions.

What you need to know about osteoporosis prevention and treatment

First, a few points about clinical studies in general. Every study has limitations, and we should keep them in mind while interpreting the results. For example, the population that was studied might be different from the one you belong to, so the results might not be applicable to you. Also, the number of subjects enrolled in the study and any confounding factors — other things that could influence the study results, such as lifestyle factors — should be taken into account when drawing conclusions. Despite these limitations, we have learned quite a lot about the benefits and harms of osteoporosis treatments.

- To date, the consensus is that there has been no proven risk of increased cardiovascular risk with intake of calcium supplements.

- Other studies have examined the risk of damage to jaw tissue with the use of bisphosphonates, one type of medication commonly used to treat osteoporosis. The risk is real, but rare. Most often, it is associated with bisphosphonates given intravenously, not taken by mouth (as most bisphosphonates are). Certain population groups are also at higher risk for necrosis than others. Talk to your doctor about your personal risk for serious bisphosphonate side effects.

- Another common question is whether osteoporosis medications are harmful to your esophagus and the rest of your digestive tract. There is a risk of inflammation of the gut lining, but if you follow the directions carefully while taking the medication and follow up with your physician as directed, the risk is very small.

- Because osteoporosis is a silent disease until a fracture occurs, women often question the need for treatment at all. There are guidelines and tools designed to help you and your doctor decide whether to start treatment, and as a patient, you have the right to know every detail of the treatment options being offered. One of the many available resources to get more information about this disease can be found here.

Your doctor should be able to help you decide by providing all the relevant information and explaining the major side effects of any treatment he or she recommends. From there, you should be an active participant in your own care. Weigh the risks and benefits in your own mind — and with your doctor — before you decide about treatment for osteoporosis.

About the Author

Maneet Kaur, MD, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.