Nutrition

Sugar: How sweet it is... or is it?

Research studies over the past 30 years have shown that high consumption of added sugar, especially from sugar-sweetened beverages, contributes to obesity, heart disease, and type 2 diabetes. The most recent data in 2018 from the CDC shows that 42.7% of US adults are obese (defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater). Furthermore, childhood obesity is a serious problem in the US, with the prevalence of obesity at 19.3% and affecting about 14.4 million children and adolescents ages 2 to 19. One in two US adults has diabetes or prediabetes, and about 50% of adults have cardiovascular disease.

What is the potential benefit from a national program to reduce sugar?

A recent study published in the American Heart Association's journal Circulation examined a model to estimate changes in cardiometabolic disease (specifically type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and obesity) and health care costs if sugar reduction targets were initiated. In 2018, the US National Salt and Sugar Reduction Initiative (NSSRI) proposed voluntary national sugar reduction targets. For each of 15 food categories, the targeted reduction in average sugar content was 20% by the end of 2026, except for sugar-sweetened beverages, which were targeted for reduction by 40%. The model looked at diet data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 2011 to 2016, sugar-related diseases from numerous other research studies, and health-related costs.

Results from the study estimated that a government-supported sugar reduction policy could prevent approximately 2.5 million cardiovascular disease events (stroke, heart attacks, and cardiac arrests); 500,000 cardiac deaths; and 750,000 cases of diabetes over the lifetimes of adults in the US ages 35 to 80. The data also showed that this reduction of sugar could save $160.88 billion net costs from a societal perspective over a lifetime.

Natural sugars and added sugars: What's the difference?

Naturally occurring sugars are found naturally in foods such as milk (lactose) and fruit (fructose). Any product that contains milk (yogurt, milk, and cream) or fruit (fresh, dried, and frozen) contains some natural sugar.

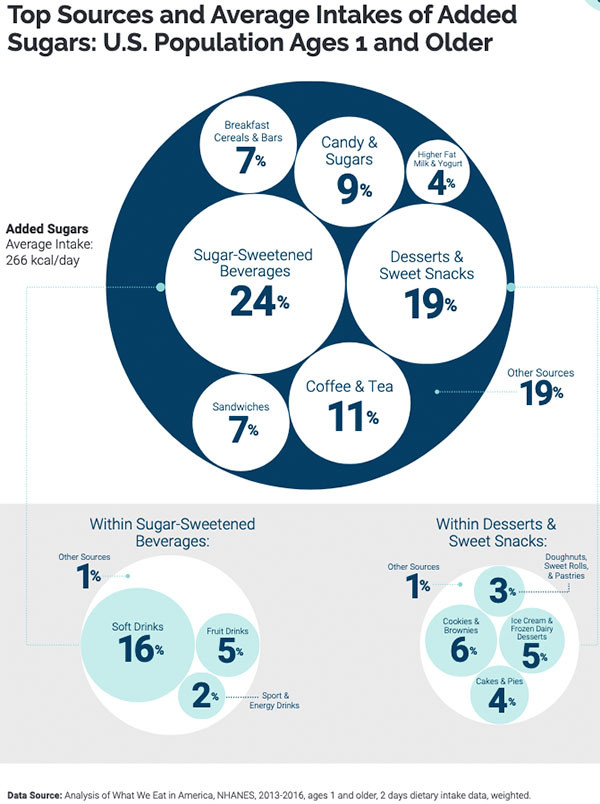

Added sugars include any sugars or caloric sweeteners that are added to foods or beverages during production or preparation (such as putting sugar in your coffee or adding sugar to your cereal). The leading sources of added sugars in the US diet are sugar-sweetened beverages, and desserts and sweet snacks. Examples of desserts and sweet snacks are cookies, brownies, cakes, pies, ice cream, frozen dairy desserts, doughnuts, sweet rolls, and pastries. Added sugars includes natural sugars such as white sugar, brown sugar, and honey, as well as other caloric sweeteners that are chemically manufactured (such as high fructose corn syrup).

The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends that women limit added sugar to no more than 6 teaspoons a day (24 grams) and men limit added sugar to no more than 9 teaspoons per day (36 grams).

Tips to reduce added sugar

- Read the Nutrition facts food label. The food label now lists "added sugars" under total carbohydrates. Make sure you review the number of grams per serving to determine how much added sugar you are consuming. Trying to limit your added sugar intake to the AHA recommendation is a place to start.

- Review the ingredient list on the food product. There are at least 55 names for sugar listed on food labels. They can be listed as honey, sucrose, dextrose, maltose, cane syrup, molasses, high fructose corn syrup, carob syrup, corn syrup solids, dehydrated cane sugar, fruit juice, invert sugar, grape sugar, mannitol, raw sugar, rice syrup, sorbitol, beet sugar, etc. The ingredient list is another source of information to help identify heavily sugared product.

- If you are a regular user of added sugar in your coffee or tea, try to cut back to half the amount. You do not have to go cold turkey. Gradually getting accustomed to less sweet beverages and foods is an adjustment. Remember, one teaspoon of sugar is equal to 4 grams of added sugar, so this needs to be included in your daily limit.

- If you have a serious sweet tooth, keep track of how many sweets or foods with large amounts of added sugar you consume in a day or week. For instance, if you eat a sweet twice a day — an afternoon granola bar and ice cream at night — start by bargaining with yourself to limit to one sweet a day. In two weeks, you might consider reducing your sweets to five days a week versus seven days, and so on. Gradually reducing in this way can support not feeling totally deprived of your sweet treat and not feeling guilty when you do have a sweet, since it is part of your plan.

- If you do drink sugar-sweetened beverages, you might start by reducing the portion size: for example, decreasing from a 12-ounce serving to a 6-ounce serving. Another strategy is to replace these types of beverages with a flavored seltzer, or water with a hint of lime or a splash of fruit juice.

The impact of added sugar on our health and health care costs is staggering. On an individual level, there are a few strategies to begin the journey to reduce added sugar in our own diets. On a societal level, getting behind a government-sponsored reduction of added sugar may help save lives and significantly reduce health care costs.

About the Author

Katherine D. McManus, MS, RD, LDN, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.