Harvard Health Blog

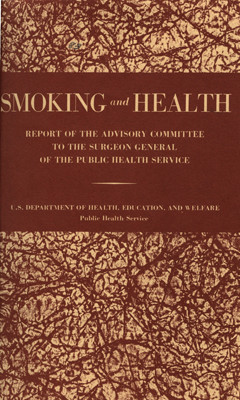

Surgeon General’s 1964 report: making smoking history

On a Saturday morning 50 years ago tomorrow, then Surgeon General Luther Terry made a bold announcement to a roomful of reporters: cigarette smoking causes lung cancer and probably heart disease, and the government should do something about it.

Terry, himself a longtime smoker, spoke at a press conference unveiling Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee of the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. That press conference was held on a Saturday in part to minimize the report’s effect on the stock market. After all, in 1964 smoking was common, fashionable, and done everywhere. In the U.S., tobacco was an even bigger business than it is today.

I vividly remember hearing about the Surgeon General’s report on the CBS Evening News. At the time, I was a first-year medical student. Between two-thirds and three-quarters of my fellow students were smokers. By the time we graduated, only 10% remained smokers. The report was one big reason why.

The impact of the report was augmented by our experience dissecting cadavers. The lungs of non-smokers were pink. The lungs of heavy smokers were black. That didn’t look healthy, and the surgeon general confirmed that it wasn’t.

I also remember the impression the report had on my mother, who had been smoking for many years. She wasn’t wowed by the science or the weight of the evidence. Instead, she was impressed by the fact that America’s “top doctor” was advising her, and other others like her, to stop smoking. (She didn’t follow his advice right away, but eventually did.)

The 1964 Surgeon General’s report, and others that followed, have had a profound effect on the health of Americans, despite the tobacco industry’s concerted and continuing efforts to promote smoking. The percentage of Americans who smoke dropped from 42% in 1964 (the peak year for smoking) to 18% today. A new report in JAMA estimates that the decline in smoking prevented 8 million deaths since 1964, more than half of them among people under age 65.

The 1964 Surgeon General’s report, and others that followed, have had a profound effect on the health of Americans, despite the tobacco industry’s concerted and continuing efforts to promote smoking. The percentage of Americans who smoke dropped from 42% in 1964 (the peak year for smoking) to 18% today. A new report in JAMA estimates that the decline in smoking prevented 8 million deaths since 1964, more than half of them among people under age 65.

But we still have a long way to go. Some 42 million Americans still smoke, although the majority want to quit. Each year, tobacco use accounts for nearly 500,000 deaths in the United States and 5 million deaths worldwide. And in the developing world, the last statistics I saw said that smoking is on the increase.

We continue to learn about the hazards of smoking and other forms of tobacco use. As CDC Director Thomas Frieden put it in a JAMA editorial, “Tobacco is, quite simply, in a league of its own in terms of the sheer numbers and varieties of ways it kills and maims people.” We also continue to learn about the addictive power of nicotine, and the difficulty of breaking an addiction to it.

The good news is that it’s possible to quit smoking. In the U.S. today, there are more former smokers than current smokers. Some people manage to quit on their own. Others are assisted by nicotine replacement coupled with some form of talk therapy. Stop-smoking medications such as varenicline (Chantix) or bupropion (Zyban) can also help.

I don’t recall hearing about any Surgeon General’s report before Dr. Terry’s 1964 report. In fact, I’m not sure at the time that I knew the U.S. had a Surgeon General. Since 1964, many Surgeon General’s reports have been issued, and many have received a lot of publicity. But probably no subsequent report has had as powerful an impact on the health of Americans.

I have many heroes. I don’t think you can overdo having heroes. Surgeon General Terry, and the epidemiological scientists who collected the evidence that he used, are near the top of my list. I’ll bet the eight million people who didn’t die young because of Dr. Terry’s message, and their loved ones, would agree.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.