Treatments for rheumatoid arthritis may lower dementia risk

Suppressing inflammation may be the key.

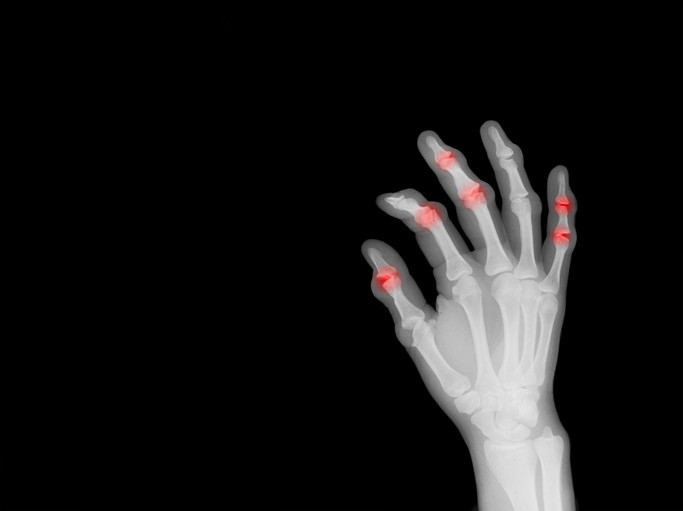

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune condition affecting up to 3% of the population. Joint inflammation, the hallmark of the disease, causes swelling, stiffness, and limited motion, especially in the small joints of the hands and wrists.

But inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis isn't limited to the joints — it's present throughout the body. As examples, skin nodules, eye inflammation, and lung scarring are well-recognized features of rheumatoid arthritis, all related to unchecked inflammation. Interestingly, inflammation may play a major role in dementia. So, could inflammation-suppressing medicines for rheumatoid arthritis affect the odds of developing dementia?

Can treatment of rheumatoid arthritis lower dementia risk?

Recent studies suggest that the answer may be yes. Perhaps this shouldn't be surprising. The role of inflammation in Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia has been a focus of research for decades, and treatments for rheumatoid arthritis reduce inflammation.

Considering that there are currently no effective preventive treatments for Alzheimer's disease or other forms of dementia, the observation that RA treatments might prevent dementia could be groundbreaking.

What's the evidence supporting this idea? Here are a few of the latest and most compelling observational studies.

- A study published in 2019 reported that people with RA treated with standard medications had less than half the risk of developing dementia over a five-year period compared with people without RA.

- A 2021 study found dementia rates declined among people with RA and increased among the overall population in recent decades. During that time, treatments for RA had been improving.

- A 2022 study looking at people taking different types of RA treatment provides some of the most convincing findings. It found that people with RA taking the newest, most effective treatments developed dementia 19% less often over the three years of the study compared with those treated with older medicines. When people taking a range of newer medicines were compared, there was no significant difference in the dementia rate.

Together, these studies suggest that certain treatments that help rheumatoid arthritis might do more than protect the joints; they might also protect the brain. This isn't the first time a medicine was found to cause an unexpectedly positive side effect. But it could be one of the most important.

Is additional research needed?

While evidence is mounting that inflammation-suppressing medicines might reduce dementia risk, more research is needed:

- Observational studies cannot prove cause. They simply observe rates of dementia among different groups of people, which means other factors could account for the results. For example, the 2022 study didn't assess smoking and family history, which contribute to dementia. If the group receiving older RA treatments had more risk factors for dementia, the medicines might not explain the findings. More powerful evidence comes from randomized controlled trials, in which otherwise similar people are randomly assigned to different treatment groups and their health is analyzed over time.

- Results might differ with different or more diverse groups of study participants. For example, participants in the 2022 study were older adults (average age 67), mostly white (75%), and mostly female (80%).

- Independent research is necessary to confirm results. A single study from one group of researchers is rarely convincing, especially for an issue as important as preventing dementia.

- Longer-term follow-up is needed. Rheumatoid arthritis is a lifelong disease, so studies lasting three to five years may not tell the whole story.

- We're not sure how certain medicines for RA might protect the brain. We also don't know whether these treatments could be effective for people who don't have RA.

It's reasonable to believe that reduced inflammation, rather than a particular drug, is providing a benefit because different medicines with different ways of damping down inflammation have been linked to lower dementia risk in people with RA. But we'll need more research to prove that's true.

The bottom line

Treatments developed over the last 50 years have transformed rheumatoid arthritis from an often disabling disease to a chronic condition that usually can be well-controlled. The initial choice of treatment depends on a combination of factors, including effectiveness, side effect profile, how a drug is given (most people prefer pills over injections), cost, and whether a drug is covered by health insurance.

Soon, another consideration may be added to this list: the ability of a medicine to lower dementia risk. This might be particularly relevant to the person with rheumatoid arthritis who has a strong family history of dementia.

And what about people without RA? I think it's only a matter of time before studies explore whether anti-inflammatory medicines can reduce the risk of dementia even in people without an inflammatory condition like RA. While it's impossible to predict what those studies will show, one thing's for sure: the impact of a positive study would be enormous.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.