Harvard Health Blog

What’s it like to be a healthcare worker in a pandemic?

We all know that some jobs are more dangerous than others. Truck drivers, loggers, and construction workers are more likely to die on the job than most others. Firefighters and police officers also face more than the average amount of risk while at work. It’s expected that people who take on these jobs understand the risks and follow guidelines to stay as safe as possible.

But what would you do if your job suddenly became much more dangerous? And what if your workplace was unable to follow recommended guidelines to reduce that increased risk?

That’s the situation now facing millions of healthcare workers who provide medical care to patients, including nurses, doctors, respiratory therapists, EMTs, and many others. They have a markedly higher risk of becoming infected with the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, especially if they are exposed to a high volume of sick patients (such as in the emergency room) or respiratory secretions (such as intensive care unit healthcare providers). Early in the outbreak in China, thousands of healthcare workers were infected, and the numbers of infected healthcare workers and related deaths are now rising elsewhere throughout the world.

While consistent use of personal protective equipment (PPE), such as N95 medical masks, reduces the risk of becoming infected with the new coronavirus, PPE is in short supply in many places.

The challenges now facing healthcare workers

Outside of work, people who have healthcare jobs have the same pandemic-related stressors as everyone else. On top of these worries come added challenges, including

- the fear and uncertainty of a heightened risk of infection

- worry that they may carry the COVID-19 coronavirus home and infect loved ones

- a dwindling or already inadequate supply of PPE needed to minimize the risk of infection

- ever-changing recommendations from local leadership, medical and public health experts, and political leaders

- unusually high and increasing demands to work longer hours as their colleagues become sick or are quarantined

- balancing their commitment to help others (which likely led them to their current profession in the first place) with an understandable commitment to protect themselves and their loved ones.

And when ICU beds, ventilators, or staffing prove inadequate to meet demand, some healthcare workers will have to make enormously distressing and difficult ethical decisions about which patients get lifesaving care and which do not.

An echo from the AIDS crisis

I remember well the uncertainty and fear surrounding the earliest days of AIDS decades ago. There were healthcare professionals who were reluctant to treat (or even touch) people with HIV infection. Soon, it became clear that HIV was transmitted primarily by blood exposure or sexual contact. As a result, simple precautions made it quite unlikely that healthcare workers would become infected with HIV by treating patients with AIDS.

But this new coronavirus is a respiratory virus. Because personal protective equipment is being rationed in some cases and has not even been universally adopted, it is far easier for healthcare workers to be infected with the new coronavirus. And it’s terribly frightening to be on the front lines of treating a new — and potentially deadly — contagious disease about which so much is uncertain.

How have healthcare workers responded?

By all accounts, healthcare workers have responded exceedingly well. They are showing up. They are putting in long hours. They have rapidly adapted to the situation by changing how they provide care, revising schedules, embracing telehealth, and even repurposing facilities — for example, turning operating rooms into intensive care units — or creating improvised protective equipment, though that’s far from ideal. And they have continued to demonstrate compassion and a brave front despite the fears they may harbor.

Remarkable stories are circulating about the lengths to which healthcare workers are going in order to protect themselves and their families: doctors staying in the garage, hotels, or rental apartments rather than returning home to risk unwittingly infecting a family member; healthcare workers avoiding their small children when they come home until they can change out of their work clothes. And I learned of a nurse who had recently given birth and decided to self-quarantine out of concern she might infect her newborn; she pumped breast milk and left it outside her door for her husband to feed to their baby. (See this link for more information about pregnancy and breastfeeding during the COVID-19 pandemic)

All of this takes a toll, of course. Already, reports are surfacing describing the significant psychological distress healthcare workers are experiencing.

The bottom line

We know how to protect healthcare workers from this new virus. Fixing the lack of masks and other protective equipment must be a priority: not only is the healthcare system obliged to protect its workers but, importantly, if enough healthcare workers get sick, our healthcare system will collapse. This will become even more important in the coming weeks, when the volume of COVID-19 cases in many areas is expected to peak.

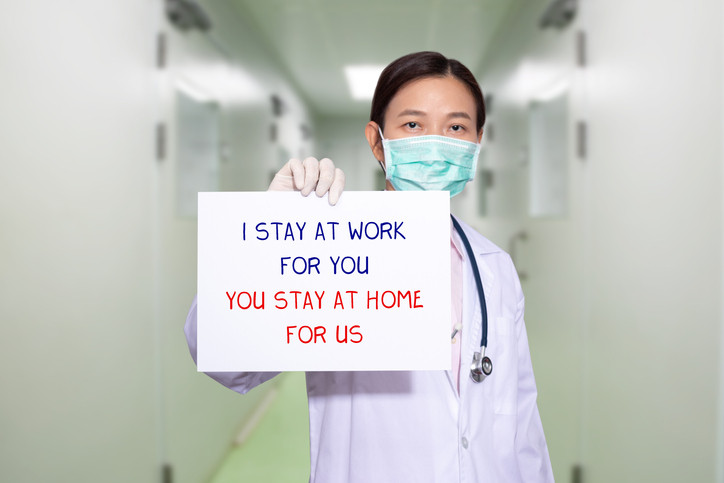

Nurses, doctors, and other healthcare workers did not sign up for such a dangerous job. So, take a moment to recognize the healthcare workers you know personally or see for medical care (as this man did). Dealing with this pandemic is not easy for anyone, but it’s especially hard on healthcare workers. Let them know you are glad they’re there for you.

When life has returned to some sense of normalcy, I am hopeful that the bravery, commitment, and yes, heroism of healthcare workers throughout this crisis will be recognized and appropriately acknowledged.

Follow me on Twitter @RobShmerling

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.