Who needs treatment for ocular hypertension?

A long-term study explores risk factors for glaucoma and treatment options for people with high eye pressure.

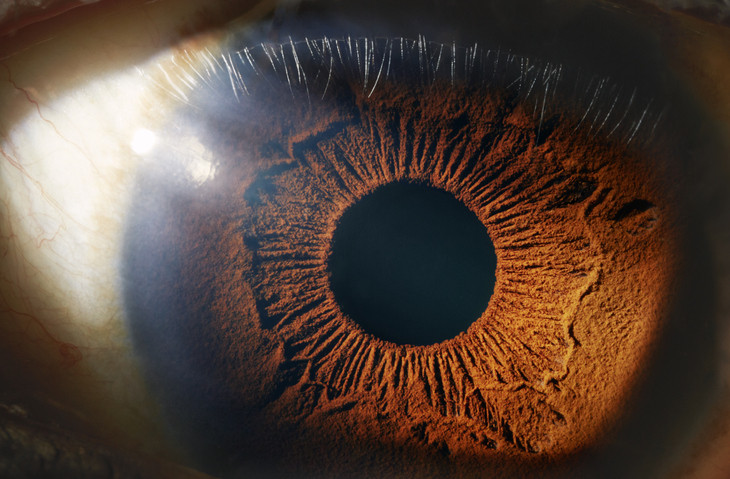

Often described as the silent thief of sight, glaucoma is the most common cause of irreversible blindness in the world. High pressure in the eye damages the optic nerve, first stealing peripheral vision (what you see at the corners of your eyes) and later harming central vision (what you see when looking straight ahead). Usually, people notice no symptoms until vision loss occurs.

Lowering high eye pressure is the only known treatment to prevent or interrupt glaucoma. But does everyone with higher-than-normal eye pressure need to be treated? A major long-term study provides some clues, though not yet a complete answer.

Does everyone with high eye pressure develop glaucoma?

In the US, glaucoma affects an estimated three million people, half of whom do not know that they have it. An ophthalmologist can perform a comprehensive eye exam to determine if someone has glaucoma, or is at risk for developing it in the future due to high eye pressure (ocular hypertension). Research from the long-running Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) shows that some people with high eye pressure may never develop glaucoma, while others will.

Launched in 1994 as a multicenter, randomized clinical trial, OHTS continues to inform our understanding of people who have high eye pressure, their risk of developing glaucoma, and whether they can take medications to prevent glaucoma.

The researchers enrolled a diverse group of 1,636 participants with ocular hypertension from 22 sites across the US. To study glaucoma prevention, participants were randomly assigned to start either early eye pressure-lowering eye drops (medication group) or close observation (control group).

At five years the data showed that 4.4% of participants developed glaucoma in the medication group, compared to 9.5% in the control group. This tells us that early use of medicated eye drops helps delay over 50% of glaucoma cases in people with ocular hypertension.

During later phases of the study, the control group could receive eye pressure-lowering medications to see whether starting medication later could still delay glaucoma; it did. At 20 years, about 49% of those in the control group and 42% of those in the medication group developed glaucoma. However, since the study was no longer randomized, the researchers were unable to compare the 20-year risk reduction between the initial starting groups.

Who took part in the study?

A high proportion of study participants (25%) were Black, which is important because minorities have historically been underrepresented in clinical trials. The other participants were mostly white. Ages ranged from 40 to 80 years (the average was 55). Except for ocular hypertension, all participants had normal eye exams, normal vision, and eye anatomy known as open angles. None had pre-existing glaucoma.

Has this research changed thinking on when to start treating glaucoma?

At first glance, the five-year data suggested that Black individuals had a higher rate of glaucoma than people of other races. However, this apparent difference disappeared when the researchers controlled for important characteristics such as age, thickness of the cornea, a measure called optic nerve cup size, and initial peripheral vision test scores.

Glaucoma risk, it turned out, did not depend solely on eye pressure and race, but on a combination of exam findings. This information helps guide clinicians in determining whether a person with ocular hypertension is at a low, medium, or higher risk for developing glaucoma. Having such information could help people decide when to begin using medicated eye drops to prevent vision loss or slow its progress.

What are the limitations of this long-term study?

The study has several limitations:

- Trial participants usually comply better with medications and appointments than those not participating, which might make real-world rates of glaucoma higher than what occurred with either group in the study.

- While the first five years of OHTS were randomized, during later phases both groups could receive eye pressure-lowering medications. By 20 years, most participants were using these medications: about 81% in the medication group and 66% in the control group. That makes it hard to compare the long-term effect of each starting approach.

- Glaucoma detection has improved over the years, with new diagnostic tests such as ocular coherence tomography and newly discovered risk factors such as corneal hysteresis. This may further support watchful waiting as a reasonable option for people at lower risk for glaucoma based on a combination of factors.

And, of course, study results do not apply to those who already have glaucoma or other eye diseases, and the eye anatomy known as narrow angles.

What's the bottom line?

Overall, the 20-year follow-up data supports making decisions on preventive glaucoma therapy for people with ocular hypertension based on a combination of additional exam findings. People with a higher number of risk factors — including higher eye pressures, older age, thinner corneas, larger optic nerve cup sizes, and worse initial peripheral vision test scores — are more likely to develop glaucoma.

If you have ocular hypertension, particularly combined with several other risk factors, eye pressure-lowering eye drops or a brief office procedure known as selective laser trabeculoplasty can help prevent glaucoma. If you have ocular hypertension and fewer additional risk factors, you can likely delay treatment if you receive regular exams to detect early signs of glaucoma. But because glaucoma is an often silent condition, anyone who has ocular hypertension should receive lifelong monitoring regardless of treatment status.

About the Author

Daniel M. Vu, MD, Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.