Teaching T cells to fight cancer

CAR T-cell immunotherapy helps the immune system seek out and kill cancer cells.

CAR T-cell immunotherapy adds a new weapon in the fight against cancer. Immunotherapy, one of the most exciting advances in cancer treatment, helps the immune system better target and kill cancer cells by focusing only on the cancerous cells while sparing the healthy ones.

CAR T-cell immunotherapy adds a new weapon in the fight against cancer. Immunotherapy, one of the most exciting advances in cancer treatment, helps the immune system better target and kill cancer cells by focusing only on the cancerous cells while sparing the healthy ones.

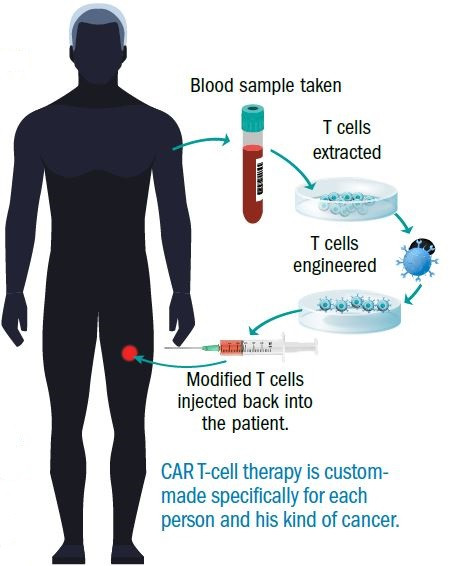

One of the most innovative immunotherapies today is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which is custom-made for individuals and their specific cancer.

"It can be an alternative for people who are resistant to chemotherapy, or diseases that don't respond well to it," says Dr. Caron Jacobson of Harvard-affiliated Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

How CAR T-cells fight cancer

Since the immune system's job is to seek out and defeat foreign invaders, it makes sense that the immune response would be the perfect cancer fighter. "Yet, sometimes the immune system doesn't recognize cancer cells as a threat," says Dr. Jacobson. "It looks the other way as the cancer cells grow."

CAR T-cell therapy helps to correct this problem by giving the immune system clearer directions for recognizing and fighting cancer cells. Those directions are aimed at T cells—white blood cells that are at the center of the immune system's response to infections, viruses, and diseases. T cells are like soldiers that seek out and defeat enemies.

CAR T-cell therapy works like this: Doctors collect a patient's T cells and place a protein on the outside of the cells. The engineered T cells are then injected back into the patient. The added protein has two roles: it guides the T cell directly to the tumor, and on arrival, it triggers the T cell's fighting power to attack the cancer cells. "This way you are attacking the cancer cell from the outside rather than from the inside, like with chemotherapy," says Dr. Jacobson. "That's why this therapy can be effective even after chemotherapy has stopped working. It is not subject to the same mechanisms of resistance."

However, the challenge with CAR T-cell therapy is that you have to find the right protein to target. "The protein needs to be on all or most of the cancer cells and not on the healthy cells that you need to survive," says Dr. Jacobson.

If you target a protein that's on only a few cancer cells, the rest have a chance to survive and grow. If the protein is found elsewhere, that raises the possibility that healthy tissues will be attacked, too.

"This is why this therapy has so far been restricted to a few cancer subsets, and has not been developed more broadly," says Dr. Jacobson.

The future of CAR T-cell immunotherapy

Still, CAR T-cell therapy has proved quite effective in treating certain cancers. Researchers have had the most success treating B-cell cancers, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Here, CAR T-cell therapy focuses on a protein on the surface of all B cells, even the healthy ones, called CD19. "Because we can live without healthy B cells, these diseases are good candidates for the therapy," says Dr. Jacobson. So far, the therapy has had response rates as high as 70% to 90%.

CAR T-cell therapy is a fast-paced research field, and Dr. Jacobson predicts that in the next two to three years, more cancers will be treated this way. Right now, T-cell therapy is being developed for brain tumors, sarcoma (a type of cancer that develops from certain tissues, like bone or muscle), prostate cancer, and lung cancer.

The first CAR T-cell products now are being considered for FDA approval. The therapy will likely be covered by insurance, says Dr. Jacobson, but it is not yet clear how much of the cost will be covered. Also, its ultimate role in cancer treatment is still unknown.

"It is unlikely CAR T-cell therapy will replace first-line cancer treatment," she says, "but it would be reserved for cancers that have not responded to, or have relapsed after, standard therapies."

CAR T-cell therapy side effects

A common side effect of CAR T-cell therapy is cytokine release syndrome, or CRS, which is associated with symptoms like fever, low blood pressure, difficulty breathing, and problems with multiple organs, including kidney failure, liver injury, and in extreme cases, heart attack.

CAR T cells in B-cell cancers also may affect the brain, which can cause people to become confused, have difficulty speaking, and become sleepy. In most cases, the symptoms are mild, manageable, and reversible, but some patients have died of treatment side effects.

Image: © ksenia_bravo; © ttsz; © e-crow; © alaroarts/Thinkstock

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.