Celiac disease

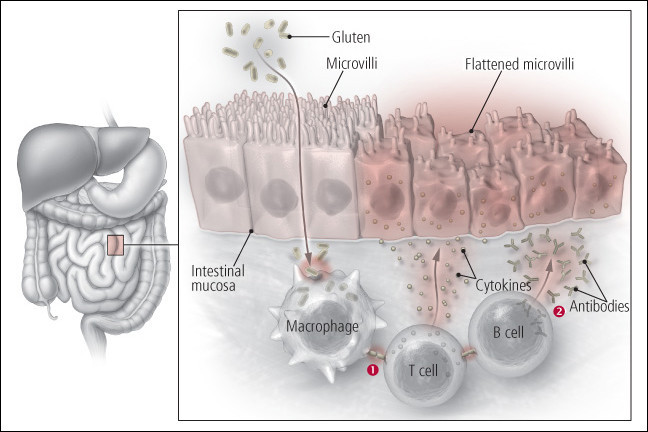

Celiac disease (also known as non-tropical sprue and celiac sprue) is a genetic, autoimmune disease. The immune system mistakenly recognizes gluten, a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley, as "foreign." When people with celiac disease eat foods containing gluten, the immune system attacks the gluten when it gets into the small intestine.

As the immune system wages war against gluten, it damages small, fingerlike projections in the small intestine called villi. Villi that make it easier for the body to absorb nutrients from food. As villi become eroded and flattened, they have trouble absorbing nutrients. The result is diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as a host of health problems related to malnutrition, including weight loss, anemia, osteoporosis, infertility, and nerve problems.

Symptoms and signs of celiac disease

Some people have no gastrointestinal complaints and no apparent symptoms, or their symptoms are so subtle that they never mention them to their doctor. Because the symptoms may be mild, people with celiac years often go undiagnosed for many years. When symptoms do occur, they include:

- fatigue

- abdominal bloating and pain

- diarrhea

- pale, foul-smelling, or fatty stools

- weight loss

Problems associated with celiac disease or caused by poor absorption of nutrients include:

- iron-deficiency anemia

- bone or joint pain

- arthritis

- bone loss

- tingling or numbness in the hands and feet

- missed menstrual periods

- infertility or recurrent miscarriage

- canker sores inside the mouth

Diagnosing celiac disease

Celiac disease can be difficult to diagnose because it causes many common symptoms that resemble those of many other intestinal conditions, including irritable bowel syndrome and lactose intolerance.

When doctors suspect that your symptoms are related to celiac disease or you are at increased risk for the condition, they most often order a blood test known as anti-tissue transglutaminase antibody, tTG-IgA. The blood test is both very sensitive and specific. However, the definitive test is a biopsy of the small intestine to look for damage to the intestinal villi and for inflammatory cells that signal an autoimmune reaction.

Treating celiac disease

The treatment for celiac disease—stop eating gluten—sounds simple but isn't easy. It means forgoing anything made from wheat, barley, and rye. Even a small amount of the protein can stir up trouble. A University of Maryland study showed that just 50 milligrams (mg) of gluten—a slice of wheat bread contains 2,000 mg—was enough to rev up inflammation and intestinal damage.

A gluten-free diet used to mean total abstention from foods like bread, cake, pizza, and even beer (see "Do's and don'ts of gluten-free eating"). But greater recognition of celiac disease has led to the development of hundreds of gluten-free foods, along with cookbooks that describe how to bake cookies, for example, using nut or rice flours. The Celiac Disease Foundation has detailed information at www.celiac.org.

Unfortunately, some foods that should be gluten free aren't. Take soy flour as an example. It shouldn't contain gluten. But if soybeans are transported in a truck or rail car that had previously held wheat, barley, or rye, or they are processed in a warehouse or plant that handles these grains, the soybeans and foods made from them can pick up enough gluten to fuel celiac disease.

Do's and don'ts of gluten-free eating |

||

|

Type of food |

Do not eat |

Okay to eat |

|

Grains, potatoes, flours, and cereals |

wheat, rye, or barley breads, bread crumbs, pasta, or noodles; spelt, semolina, kamut, triticale, couscous, bulgur, farina; unidentified starches or fillers; most commercial cereals |

gluten-free pastas and breads (made from soy, rice, corn, potato, or bean flours); plain rice, corn, popcorn, potatoes, sweet potatoes, soybeans and other beans, nuts, millet, amaranth, quinoa, oats (consult your doctor first), buckwheat, cornstarch, tapioca, and arrowroot starch; gluten-free cereals (such as corn and rice) |

|

Fruits and vegetables |

canned soups, soup mixes, bouillon cubes, creamed vegetables, most commercial salad dressings |

fresh, frozen, or canned fruits or vegetables, unprocessed and without sauces; homemade soups with allowed ingredients |

|

Meat, fish, poultry, main dishes |

commercially prepared fresh or frozen meat and main dishes, lunch meats, and sausages |

fresh meat, fish, poultry |

|

Dairy products |

processed cheese, cheese mixes, blue (veined) cheese; yogurt or ice cream that's unlabeled or that contains fillers or additives; low-fat or fat-free cottage cheese, sour cream, or cheese spreads |

plain, natural cheese; gluten-free plain yogurt and ice cream; whole, low-fat, and fat-free milk; full-fat cottage cheese and sour cream |

|

Alcohol |

beer, ale, stout |

gluten-free beer, wine, light rum, potato vodka |

|

Other |

grain or malt vinegar, commercial pudding mixes, malt from barley, soy sauce made from wheat |

distilled rice, wine, or apple cider vinegar; homemade puddings from tapioca, cornstarch, rice; sugar, honey, jam, jelly, plain syrup, plain hard candy, marshmallows; gluten-free soy sauce |

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.