Decoding poor circulation

Much can go wrong within the body's maze of blood vessels. Learn what contributes to circulation problems — and how they show up.

- Reviewed by Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

If hair on your toes no longer sprouts or your toenails seem to grow more slowly than ever, don't dismiss these developments as just strange new quirks.

If hair on your toes no longer sprouts or your toenails seem to grow more slowly than ever, don't dismiss these developments as just strange new quirks.

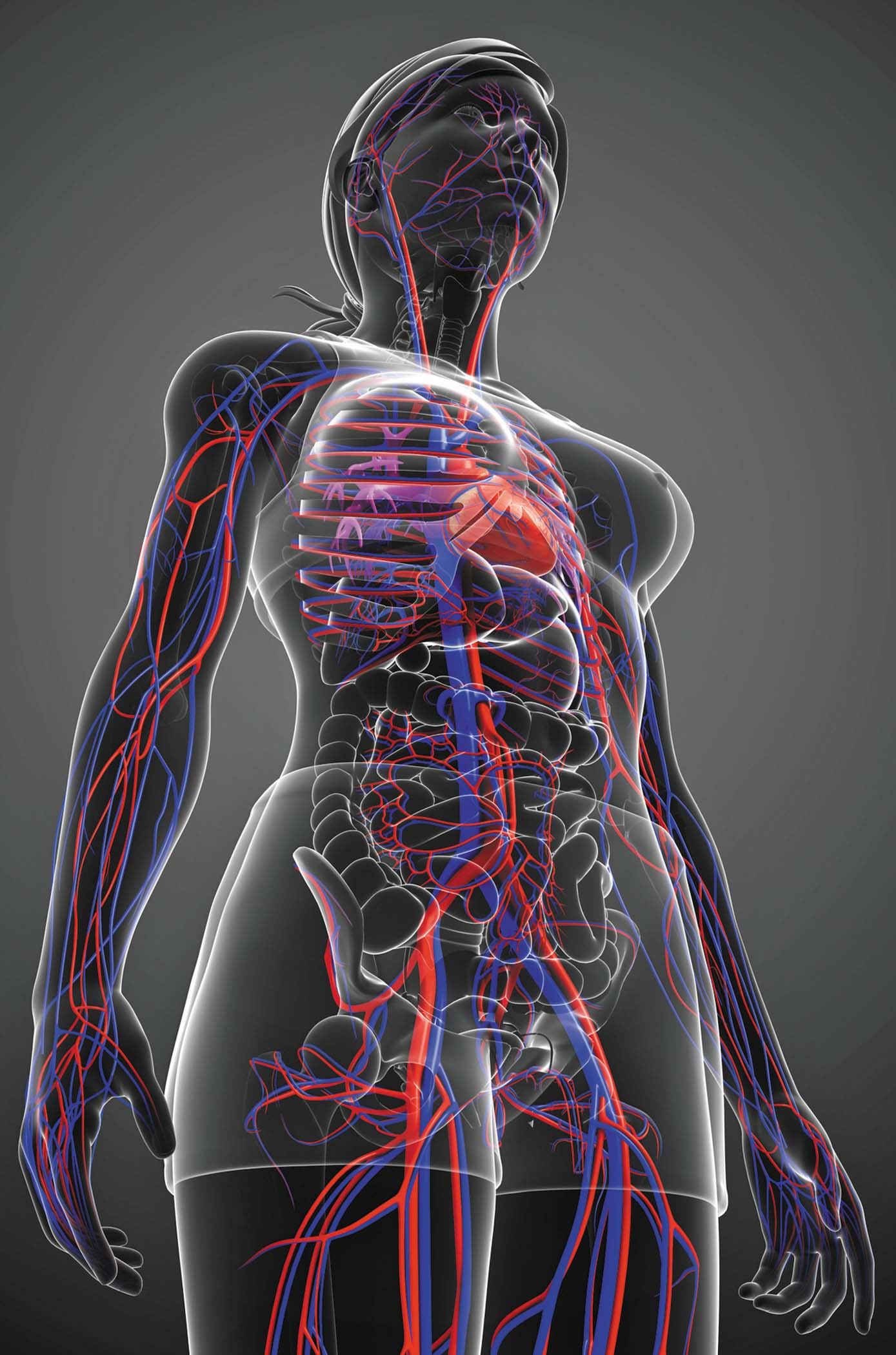

Along with buttock pain or red, tight, or shiny skin on the legs, these are lesser-known signs that your circulatory system — the 60,000-mile network of arteries, veins, and capillaries that enables blood to carry oxygen and nutrients around the body — might not be functioning as well as it should.

While all these vessels are connected, each type works quite differently. When problems develop, they show up differently as well — and often in a confusing variety of ways.

"People do pay attention to their circulation, but I don't think they understand it very well," says Dr. Dara Lee Lewis, a cardiologist specializing in women's heart health at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. "People throw around the term 'poor circulation' without necessarily having a sense of what it means."

Arteries vs. veins

Arteries and veins operate in tandem, but also in opposition: arteries deliver blood from the heart to the body, while veins return blood to the heart. This distinction influences which circulatory troubles can afflict each.

"I often think of vasculature as a whole separate organ system," says Dr. Mounica Yanamandala, a cardiologist and blood vessel specialist at Brigham and Women's Hospital. "Arteries supply blood differently to the legs than the heart, for example. And brain tissue is very different from the gut, which has moments of high demand when we eat. So the way arteries and veins have to work is very different depending on supply and demand."

Conditions involving the arteries are marked by diminished blood flow to an organ or body part. Often dangerous, they include

- recurrent chest pain (called angina)

- heart attack

- stroke

- peripheral artery disease, which reduces blood flow to muscles—typically in the legs—when plaque buildup narrows arteries far from the heart. "A red flag is pain in the leg muscles when you walk," Dr. Lewis says.

Circulation problems involving the veins often arise when valves in these vessels weaken, allowing blood and other fluids to pool and pressure to build. They include

- twisted, bulging varicose veins in the legs

- discolored skin on hands or feet

- swollen legs, ankles, or feet.

Signs to watch

Is it possible to have poor circulation and a healthy heart? Not usually. Typically, healthy blood vessels and a robust heart go hand in hand, Harvard experts say.

Circulation problems "can be like a canary in a coal mine," Dr. Yanamandala says. "Your heart pumps blood to this network of highways and small roads that all lead to your organs. So if we find disease in the arteries, we can bet there's disease elsewhere."

Because of this, you should take any signs of poor circulation seriously. Follow up with your doctor if you notice

- chest pain

- lightheadedness

- numbness, tingling, or swelling in the arms or legs

- achy muscles in your legs, calves, or feet

- muscle loss in your legs

- slow-healing wounds

- difficulty walking distances.

But some people with circulation problems notice no telltale signs. "Many people don't have any symptoms, or don't think they do," Dr. Yanamandala says. They may also mistakenly attribute any clues to getting older.

"Again and again, I see people who think their inability to walk very far is normal, just part of aging," she says. "But it's not normal."

Boost blood flow with these tasty choicesIt's no secret that a poor diet contributes to heart disease, which kills more than 2,500 Americans each day and remains the leading cause of death in the United States for both women and men. But avoiding what are often called inflammatory foods—such as red and processed meats, deep-fried items, and sugary treats—is only part of the dietary strategy to combat the diminished blood flow that characterizes heart disease and other circulatory conditions. Certain nutrients can fight inflammation, increase "good" HDL cholesterol, and help blood vessels widen to promote better blood flow and reduce clotting risk. Such anti-inflammatory foods tend to be high in antioxidants and fiber. They include

Meanwhile, foods that boost blood flow are naturally high in nitrates. These are compounds made of nitrogen and oxygen, which our bodies convert into nitric oxide—a molecule that relaxes blood vessels and may help lower blood pressure. (Foods with added nitrates, such as processed meats like bacon, hot dogs, and deli meats, do not have this effect and can be harmful when eaten often.) Foods naturally high in nitrates include

As you reach for these nourishing choices, bear in mind that doing so isn't a panacea, says Dr. Dara Lee Lewis, a cardiologist specializing in women's heart health at Brigham and Women's Hospital. "If someone's already got major blockages in their arteries, all the nitric oxide in the world is not going to help," Dr. Lewis says. But when combined with exercising regularly and minimizing risk factors such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and diabetes, healthy eating can stave off circulation woes. |

Walking as prevention

While aging itself can contribute to circulation problems, they're largely preventable if we control underlying risk factors such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. "Many medications overlap that can treat all of these," Dr. Yanamandala says.

Perhaps the best way to avoid circulatory issues — or nip them in the bud — is to walk for progressively longer periods and farther distances. "One of the coolest things about arteries and veins is they have the ability to grow to try to overcome barriers," Dr. Yanamandala says. "The best way to build up arteries is to exercise. When you increase the demand, muscles call out for more blood, and that signal actually prompts arteries to form to meet that demand."

Image: © sankalpmaya/Getty Images

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.