Diverticular disease of the colon

Learn about diverticulitis and how diverticular disease is largely preventable.

Many health-conscious peoplemen can recite their cholesterol counts and, blood pressure readings, and PSA levels without even glancing at their medical records. But few of these well-informed gents can tell you if they have diverticular disease of the colon, even though it's an extremely common condition. That's understandable, since the most prevalent form of the problem, diverticulosis, produces few if any symptoms. Still, when complications develop, blissful ignorance about diverticulosis abruptly gives way to an unwelcome education about the pain of diverticulitis or the bleeding of diverticulosis. It's a learning experience that's particularly unfortunate, since diverticular disease is largely preventable.

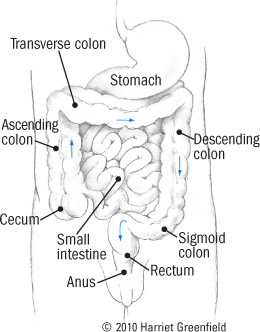

Your colon

The colon is a 4 1/2-foot-long tube that constitutes the final portion of the intestinal tract. The food you eat is mostly digested in the stomach and small intestine. Residual material enters the colon, or large intestine, in the cecum, which lies in the right lower portion of the abdomen (see Figure 1). From there, digested material travels up the ascending colon, across the transverse colon, and down the descending colon to the final portion, the sigmoid colon, in the lower left part of the abdomen. The intestinal contents take about 18 to 36 hours to journey through the colon; in the process, the few remaining nutrients are snatched into the bloodstream and much of the water is absorbed, resulting in solid fecal material.

When healthy, the colon is a smooth cylinder lined by a layer of epithelial cells. The wall of the colon contains two groups of muscles, a circular muscle that rings the colon and three long muscles that run the entire length of the tube. Like all tissues, the colon requires a supply of blood; in part, it's provided by the many small penetrating arteries that pass through the colon's muscular wall to carry blood to its inner layer of epithelial cells.

Figure 1: The colon

|

Diverticular disease

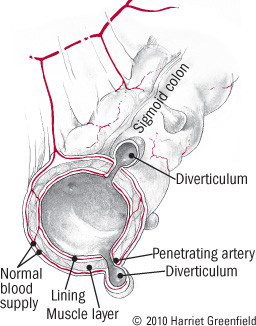

Most folks who think about the colon worry about the polyps and cancers that may develop from epithelial cells. But problems can also develop in other areas. Diverticula are sac-like pouches that protrude from the normally smooth muscular layer of the colon (see Figure 2). They tend to develop where the muscles are weakest, at the places where penetrating vessels cross through the muscles. And in Western societies, the great majority of diverticula develop where the colon is narrowest, in the sigmoid.

Figure 2: Diverticulosis

|

Who gets diverticulosis — and why?

Age is a major risk factor for diverticulosis. Diverticulosis is uncommon before age 40, but about one-third of all Americans will develop the condition by age 60, and two-thirds will have it by age 85. That makes diverticulosis one of the most common medical conditions in the United States.

It wasn't always this way. Diverticulosis was uncommon in the United States 100 years ago, and it's still rare in the developing world. What accounts for the difference? The principal factor is diet, especially the refinement of carbohydrates, which has deprived the typical American diet of much of its fiber content. Diverticulosis is a disease of Western civilization.

Dietary fiber is a mix of complex carbohydrates found in the bran of whole grains and in nuts, seeds, fruits, legumes, and vegetables, but not in any animal foods. Because humans cannot digest these complex carbohydrates, dietary fiber has little caloric value — but it has plenty of health value. Among other things, the insoluble fiber found in wheat bran, whole-grain products, and most vegetables (see table) draws water into the feces, making the stools bulkier, softer, and easier to pass. Dietary fiber speeds the process of elimination, greatly reducing the likelihood of constipation.

Some sources of dietary fiber |

|||

|

Food |

Serving size |

Fiber content |

|

|

Cereals |

Fiber One |

cup |

14 |

|

All Bran |

cup |

10 |

|

|

Shredded Wheat |

1 cup |

6 |

|

|

Oatmeal |

1 cup (cooked) |

4 |

|

|

Grains |

Barley |

1 cup (cooked) |

6 |

|

Brown rice |

1 cup (cooked) |

4 |

|

|

Baked goods |

Rye Krisp |

1 square |

3 |

|

Bran muffin |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Whole-wheat bread |

1 slice |

2 |

|

|

Legumes |

Baked beans |

1 cup (canned) |

10 |

|

Kidney beans |

cup (cooked) |

7 |

|

|

Lima beans |

cup (cooked) |

7 |

|

|

Vegetables |

Spinach |

1 cup (cooked) |

4 |

|

Broccoli |

cup |

3 |

|

|

Brussels sprouts |

cup |

2 |

|

|

Carrot |

1 medium |

2 |

|

|

Tomato |

1 medium |

2 |

|

|

String beans |

cup |

2 |

|

|

Fruit |

Pear (with skin) |

1 medium |

5 |

|

Apple (with skin) |

1 medium |

3 |

|

|

Banana |

1 medium |

3 |

|

|

Dried fruits |

Prunes |

6 |

4 |

|

Raisins |

cup |

1 |

|

|

Nuts and seeds |

Peanuts |

10 nuts |

1 |

|

Popcorn |

1 cup |

1 |

|

|

Supplements |

Wheat bran (crude) |

1 ounce |

12 |

|

Wheat germ |

1 ounce |

4 |

|

|

Psyllium |

1 tsp. or 1 wafer |

3 |

|

|

Methyl cellulose |

1 tbsp. |

2 |

|

A low-fiber diet has the opposite effect. But constipation is the least of the problems related to diverticulosis. Without enough fiber, the stools are small and hard, and the colon must contract with extra force to expel them. That puts extra pressure on the wall of the colon — and, as you may remember from Physics 101, the Law of LaPlace explains that the pressure in a tube is highest where the diameter is smallest. In the colon, that's the narrow sigmoid.

A Harvard study of 47,888 men demonstrates the role of dietary fiber. Men who consumed the most fiber were 42% less likely to develop symptomatic diverticular disease than their peers who consumed the least fiber. And the protective effect of fiber remained strong after the scientists took age, physical activity, and dietary fat into account.

Over time, a low-fiber diet increases the risk for diverticulosis and its complications. Because connective tissues tend to weaken over the years, age itself may compound the effect of diet. Other possible risk factors for diverticular disease include a high consumption of fat and red meat, obesity, cigarette smoking, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. On the other hand, a Harvard study found that regular physical activity appears to reduce the risk of diverticular disease by up to 37% in men.

Why worry?

Diverticulosis is so common in Americans that it may hardly seem like a disease. Indeed, most peopleabout 75% of men with the condition never develop serious problems from diverticulosisit, though some of them have occasional abdominal cramps that may or may not stem from diverticulosis. But some 15% to 20% of people with diverticulosis go on to develop an inflammatory complication called diverticulitis (two-thirds mild to moderate, one-third serious) and 5% to 10% develop bleeding (two-thirds mild to moderate, one-third life-threatening). In all, diverticular disease of the colon accounts for 3,400 deaths in the United States each year while draining our economy of over $2.4 billion a year. That's quite a toll for a disease you may never have heard of.

Diverticulitis: Symptoms

Inflammation puts the "itis" into diverticulitis, which is the most common complication of diverticular disease. The bacteria that are packed into feces by the hundreds of millions are responsible for the inflammation of diverticulitis, but doctors don't fully understand why some diverticula become infected and inflamed while many do not. A current theory holds that the wall of the diverticular sac becomes eroded by pressure, trapped fecal material, or both. If the damage is severe enough, a tiny perforation develops in the wall of the sac, allowing bacteria to infect the surrounding tissues. In most cases, the body's immune system is able to contain the infection, confining it to a small area on the outside of the colon. In other cases, though, the infection enlarges to become a larger abscess, or it extends to the entire lining of the abdomen, a critical complication called peritonitis.

Pain is the major symptom of diverticulitis. Because diverticulosis typically occurs in the sigmoid colon, the pain is usually most pronounced in the lower left part of the abdomen, but other areas may be involved. Fever is also very common with diverticulitis, sometimes accompanied by chills. If the inflamed sigmoid is up against the bladder, a man may develop enough urinary urgency, frequency, and discomfort to mimic prostatitis or a bladder infection. Other symptoms may include nausea, loss of appetite, and fatigue. Some patients have constipation, others diarrhea.

Diverticulitis: Diagnosis

A physician's exam may reveal tenderness over the inflamed tissues, typically in the lower left abdomen; less often, the doctor may feel swelling. As in other infections, the white blood cell counts are usually elevated. But because these findings are non-specific, further testing is required to establish a diverticulitis diagnosis. The best test is a CT scan of the abdomen, ideally performed after the patient receives contrast material both by mouth and intravenously. And a month or two later, after treatment has quieted things down, the patient should have a colonoscopy, both to evaluate the diverticular disease and to be sure that no other abnormalities are lurking.

Diverticulitis: Treatment

Since bacteria are responsible for the inflammation, antibiotics are the cornerstone of diverticulitis treatment. And because the colon harbors so many bacterial species, doctors must prescribe treatment that will target a broad range of bacteria, including Bacteroides and other anaerobic bacteria that grow best without oxygen, as well as E. coli and other aerobic (oxygen-requiring) microbes. Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (Augmentin) is effective against both types of bacteria. Another approach is to prescribe metronidazole (Flagyl, generic) for the anaerobes along with ciprofloxacin (Cipro, generic) or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, generic) for the aerobes. Needless to say, there are many variations on the theme, and doctors must always take their patients' allergies and general health into consideration when they prescribe antibiotics.

Patients with mild-to-moderate diverticulitis can take their antibiotics in pill form at home, but patients with severe inflammation or complications (see below) should receive intravenous (IV) antibiotics in the hospital, and then finish up with pills at home. In most cases, seven days of antibiotics is sufficient for diverticulitis treatment.

Bowel rest is also important for acute diverticulitis. For home treatment, that means sticking to a diet of clear liquids for a few days, then gradually adding soft solids and moving to a more normal diet over a week or two. Intravenous fluids can sustain hospitalized patients until they are well enough to switch to clear liquids en route to a full diet.

Because diverticulitis tends to recur, prevention is always part of the treatment plan. And for people with any form of colonic diverticular disease, that means a high-fiber diet.

Diverticulitis: Complications

Ordinary diverticulitis is bad enough, but complications from diverticular disease can be life-threatening. The most common complications include:

Abscess formation. An abscess is a walled-off collection of bacteria and white blood cells — pus. Diverticulitis always involves bacteria and inflammation, but if the body can't confine the process to the wall of the colon immediately adjacent to the perforated diverticulum, a larger abscess forms.

Patients with abscesses tend to be sicker than those with uncomplicated diverticulitis, and they have higher temperatures, more pain, and higher white blood cell counts. Treatment involves antibiotics and bowel rest, but it also requires drainage of the abscess. In many cases, specially trained interventional radiologists can accomplish that by using CT imagery to guide a thin plastic catheter through the skin into the abscess, allowing the pus to drain out. In most cases, the catheter stays in place for several days or until the drainage stops, while the patient continues to receive antibiotics and fluids. Sometimes, though, open surgery is required (see below).

Peritonitis. Although an abscess requires aggressive treatment, it represents a partial success for the body's infection defense apparatus, since the infection is confined to a small area. If that containment fails, infection spreads to the entire lining of the abdomen. Patients are critically ill with high fever, severe abdominal pain, and often low blood pressure. Prompt surgery and powerful antibiotics are required.

Fistula formation. In diverticulitis, the infection can burrow into nearby tissues, such as another part of the intestinal tract, the urinary bladder, or the skin. This complication is less common than abscess formation and less urgent than peritonitis, but it does require both surgery and antibiotics.

Stricture formation. It's another uncommon complication that can develop from recurrent bouts of diverticulitis. In response to repeated inflammation, a portion of the colon becomes scarred and narrowed. Doctors call such narrowing a stricture, and they must call on surgeons to correct the problem so fecal material can pass through without obstruction.

Diverticulitis: Surgery

Most patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis respond well to antibiotics and bowel rest. The majority of patients with abscesses do well with drainage through a catheter, but patients with severe diverticulitis or threatening complications require surgery. Here are some typical indications for diverticulitis surgery:

- severe diverticulitis that does not respond to medical treatment

- diverticulitis in patients with impaired immune systems

- diverticulitis that recurs despite a high-fiber diet

- abscesses that cannot be drained with a catheter

- peritonitis, fistula formation, or obstruction

- strong suspicion of cancer.

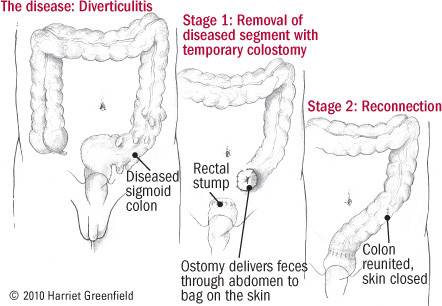

The timing and type of operation depend on the patient's individual circumstances. One traditional approach involves two separate operations, the first to remove the disease and divert the intestinal contents to a colostomy bag on the skin, and the second, several months later, to hook the colon and rectum back together (see Figure 3). In some cases, this can be accomplished with less-invasive laparoscopic surgery, and in milder cases, one operation may suffice. Still, the prospect of surgery makes a good case for eating plenty of fiber (see below).

Figure 3: Two-stage surgery for diverticulitis

|

Diverticular bleeding

Diverticulitis is one main complication of diverticular disease of the colon. The other is diverticular bleeding. It occurs when a diverticulum erodes into the penetrating artery at its base (see Figure 2). Because acute inflammation is absent, patients with diverticular bleeding don't have pain or fever.

The most common symptom is painless rectal bleeding. Since diverticular bleeding occurs in the colon, it produces bright red or maroon bowel movements. (In contrast, when bleeding occurs in the stomach, the blood is partially digested as it passes through the intestinal tract, so it appears as black, tar-like bowel movements).

In most patients, the bleeding is mild, and it usually stops on its own with bowel rest. But brisk bleeding is a life-threatening emergency. It requires expert hospital care with blood transfusions and IV fluids. It also requires aggressive attempts to locate the site of bleeding and to stop it. Several techniques are available; most experts recommend colonoscopy (doctors can see the bleeding artery through the scope and cauterize or clip it to stop the bleeding) or angiography (doctors thread a catheter into the artery that supplies blood to the colon, inject dye to see the bleeding artery on x-rays, and then inject medication to constrict the artery and stop the bleeding). If neither approach stops the bleeding, surgery may be needed.

Diverticular disease prevention

Diverticular disease of the colon is preventable. A high-fiber diet will sharply reduce the risk of developing diverticula — and even after the pouches form, dietary fiber will reduce the risk of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding.

The Institute of Medicine recommends 38 grams of fiber a day for men age 50 and under and 30 grams a day for older men. For women, the recommended amount is 30 grams a day for those age 50 and under and 21 grams a day thereafter. Most Americans get much, much less. The table lists the fiber content of some foods and supplements.

Fiber is important for bowel function and general health, but it can be hard to get used to. Many people feel bloated and gassy when they start a high-fiber diet, but if they stick with it, these side effects usually diminish within a month or so. Still, it's best to ease into a high-fiber diet. Increase your daily intake by about 5 grams per week until you reach your goal, and be sure to have plenty of fluids as well. For most people, a high-fiber cereal is the place to start, but if breakfast isn't your thing, you can have it any time during the day.

Until recently, doctors banned nuts, seeds, corn, and popcorn from the diet of diverticulosis patients. Although they had no real evidence that these foods were harmful, doctors worried that these small particles might pass into the colon undigested and then lodge in the mouth of a diverticulum, blocking the pouch and making things worse. But a 2008 Harvard study put these fears to rest. During the 18-year study, the men who ate the most nuts and popcorn actually had a lower risk of acute diverticulitis than the men who ate the least; there was no change in the risk of bleeding, for better or worse.

Scientists are experimenting with other ways to prevent attacks of diverticulitis and episodes of bleeding; among other things, long-term nonabsorbable oral antibiotics are under study. People with diverticular disease might be wise to avoid or minimize their use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, which may (or may not) increase the risk of trouble. Even so, dietary fiber remains the key to preventing diverticulitis and its complications. And if that's not enough reasons to chow down lots of "roughage," consider the other benefits of a high-fiber diet.

Dietary fiber fights constipation. Because it reduces straining that puts pressure on the abdomen and the veins, fiber reduces the risk of hernias, hemorrhoids, and even varicose veins. In some, but not all, studies, fiber has been linked to a reduced risk of colon cancer. Fiber is filling, and it helps combat obesity. It improves blood sugar metabolism, lowering the chances of developing diabetes. It lowers blood pressure. Some forms of fiber (soluble fiber) reduce blood cholesterol levels, and according to a Harvard study of 43,757 men, a high-fiber diet appears to reduce the risk of heart attacks by 41%.

Image: Alina555/Getty Images

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.