Dizziness demystified

Vertigo can be disturbing and destabilizing. Learn what can trigger this common problem.

- Reviewed by Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

"Like a whirlpool, it never ends." This apt description of vertigo from Tommy Roe's 1969 hit "Dizzy" was fun to listen to when we were kids, but not so amusing decades later if you've endured the room-spinning sensation.

"Like a whirlpool, it never ends." This apt description of vertigo from Tommy Roe's 1969 hit "Dizzy" was fun to listen to when we were kids, but not so amusing decades later if you've endured the room-spinning sensation.

Originating from the Latin word vertere, meaning "to turn," vertigo can also make you feel unsteady on your feet, lightheaded, faint, or like you're in motion when you're not. Some people who have it also become nauseated and vomit. But whether it lasts for a few seconds or a few days, the highly common problem is rarely dangerous — though it can provoke falls, a leading cause of deaths from injuries in adults 65 and older.

Either way, it's vital to know that vertigo is a symptom, not a condition in itself. This makes it a starting point for seeking a diagnosis, not something to leave unquestioned, says James Naples, an otolaryngologist (ear, nose, and throat specialist) at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center's Dizziness Clinic.

"Telling your doctor you have vertigo is like saying you have a stomachache," Dr. Naples says. "It doesn't mean you have a solution — it means you have to look for a cause."

Common culprits

Vertigo is an equal-opportunity affliction, so there's no "typical" patient with it, Dr. Naples says. Many cases originate from the inner ear, the headquarters of our body's vestibular system, which regulates our sense of balance and spatial orientation. A smaller subset arises from problems with the way the brain interprets motion.

Minor — and quickly passing — triggers include dehydration, alcohol use, hormone shifts during perimenopause, certain foods or ingredients, stress or anxiety, and excessive tiredness.

These are the most common conditions causing dizziness:

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). Especially prevalent in older adults, BPPV occurs when tiny crystals in the inner ear (called canaliths) shift out of place. Certain head movements — such as turning over in bed — trigger intense symptoms.

Vestibular migraines. A variant of conventional migraines, this form doesn't always involve a headache but produces vertigo and other balance-related symptoms.

Vestibular neuritis. Typically caused by a viral infection, this condition (also called acute labyrinthitis) is an inflammation of the balance apparatus of the inner ear.

M'nière's disease. Often marked by ear-ringing and progressive, low-frequency hearing loss, this condition is prompted by a change in the inner ear's fluid volume stemming from a variety of possible reasons.

Treatment strategies

If dizziness is accompanied by other symptoms such as sudden changes in vision, hearing, or speech or numbness or tingling on one side of the body or face, seek emergency medical attention. "We'd want to make sure you aren't having a stroke or have another neurological condition," Dr. Naples says.

Regardless, your first vertigo attack should compel you to make a doctor's appointment, since there's no way of knowing whether the cause is minor or serious. "No exceptions," he says.

As part of your evaluation, your doctor will look for involuntary, jerking eye movements called nystagmus, as well as determine whether additional testing such as a hearing test or brain imaging is needed.

Depending on the cause, vertigo treatment can include one or more of these therapies:

- Medications to dampen the sensitivity of the inner ear, reducing dizziness and the nausea that comes with it. But drug treatment isn't a long-term solution. "Most medications only treat the symptoms without addressing the underlying cause of your vertigo," Dr. Naples says.

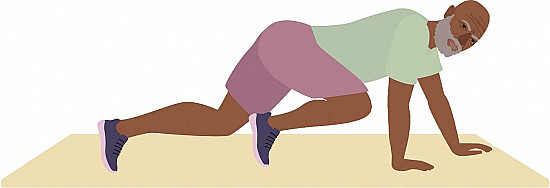

- A canalith repositioning procedure, also known as the Epley maneuver, which involves moving your head through a series of positions to shift inner-ear crystals to other areas that won't trigger dizziness.

- Vestibular therapy, or balance rehabilitation, in which you learn exercises to help you manage dizziness and balance problems. "No matter what type or degree of dizziness you have, this type of physical therapy is helpful in most cases," he says.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy, which addresses vertigo's sometimes-extreme emotional toll. "I think we get so caught up trying to treat the condition that we ignore treating the individual," Dr. Naples says.

Whether your vertigo is chronic, episodic, short, or long, resist the urge to stay sedentary when dizziness subsides. "It causes more harm than good to sit and wait for the next vertigo episode," he says. "Simply staying active is going to help."

Image: © Mykyta Dolmatov/Getty Images

About the Author

Maureen Salamon, Executive Editor, Harvard Women's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Toni Golen, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Women's Health Watch; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing; Contributor

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.