Fight back against gout

This common inflammation of the joints can be treated and managed with medication and lifestyle changes.

Gout affects more than eight million adults, six million of whom are men. It often strikes suddenly, like flicking on a light switch, and the pain is severe, with intense swelling and redness.

Food choices can dictate if you get gout, as high intake of organ meat, shellfish, and alcohol can raise your risk. But diet is only a part of it. "There is a direct relationship between advancing age and gout," says Dr. Robert Shmerling, clinical chief of rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

In general, if you have one attack, there is a good chance you will have another within the next year. Even if you have avoided gout so far, you still may suffer from it in the future. Yet there are ways to reduce your risk as well as prevent repeat attacks.

An inside look at gout

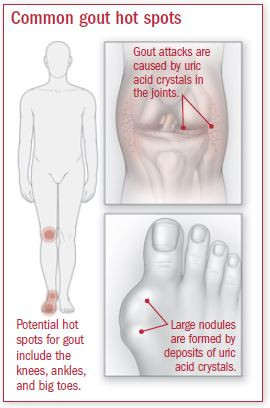

Gout is triggered by the crystallization of uric acid within the joints. It happens like this: Your body produces uric acid from breaking down purines, which are formed by the body and found in certain foods. Uric acid enters your blood and passes through your kidneys into your urine.

However, sometimes your body produces too much uric acid or excretes too little. This causes uric acid to build up and form needle-like urate crystals in a joint or the surrounding tissue. The result: a sudden, painful flare-up.

The large joint of the big toe is the most common affected area, followed by the side of the foot and ankle. Other hot spots include the knees, hands, and wrists. Most episodes last approximately seven to 10 days.

While gout can occur at any time, it is most likely to strike at night or early morning. The main reasons for this are believed to be lower body temperature and nighttime dehydration. "Crystals are more likely to form in lower temperatures, and dehydration can prevent excess uric acid from being flushed from the body," says Dr. Shmerling.

|

|

Treating attacks

The best way to confirm gout is with a joint fluid test to reveal urate crystals. A blood test given by your doctor to measure your uric acid level can also contribute to the overall diagnosis, as the higher the level, the greater your risk. For attacks, the first line of treatment is medication, says Dr. Shmerling. There are several types, but the most common include the following:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). These are over-the-counter options, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen sodium (Aleve), as well as prescription NSAIDs like indomethacin (Indocin).

-

Colchicine. This relieves gout pain. After the pain resolves, your doctor may prescribe a low daily dose along with a urate-lowering medication to prevent future attacks.

-

Corticosteroids. These may control inflammation and pain, and may be taken in pill form or injected into your joint.

If you suffer chronic or frequent attacks, if more than one joint is affected, or if you develop kidney stones or a tophus (a large lump of crystals), you may need medication to reduce uric acid production. The usual goal here is to lower uric acid levels to less than 6 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL).

Dietary changes

Medication is only one way to prevent gout attacks. Altering your lifestyle habits can add further protection.

Besides reducing your intake of meat and shellfish, which can raise uric acid levels, limit your intake of alcohol as well as drinks with high-fructose corn syrup, like soft drinks, says Dr. Shmerling. Stay well hydrated and adopt an exercise program to help lose excess weight.

You can also increase your intake of foods that have been shown to lower uric acid levels, like coffee (regular or decaf) and cherry juice, as well as increasing your vitamin C intake through supplements or foods, such as bell peppers, broccoli, strawberries, and oranges. But keep in mind that these dietary changes have their limits.

"If you have a high level of uric acid—for example, 10 mg/dL—you may be able to lower it to 9.5 mg/dL through your diet, but you are still considered at a high risk for repeat attacks," says Dr. Shmerling.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.