HIV/AIDS

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

What is HIV/AIDS?

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) weakens the body's immune defenses by destroying CD4 (T-cell) lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. T-cells normally help guard the body against attacks by bacteria, viruses and other germs.

When HIV destroys CD4 cells, the body becomes vulnerable to many different types of infections. These infections are called opportunistic because usually they only have the opportunity to invade the body when the immune defenses are weak. HIV infection also increases the risk of certain cancers, illnesses of the brain and nerves, body wasting, and death.

The range of symptoms and illnesses that can happen when HIV infection severely weakens the body's immune defenses is called acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or AIDS.

Since 1981, when doctors first recognized HIV/AIDS as a new illness, scientists have learned much about how a person becomes infected with HIV. The virus is spread through contact with an infected person's body fluids, especially through blood, semen and vaginal fluids. HIV can be transmitted:

- during sex (anal, vaginal, and oral)

- by contaminated blood (by sharing or accidentally being stuck with a contaminated needle

- through transfusions before blood products started being screened for HIV in 1985)

- by being born to a mother who is infected with HIV.

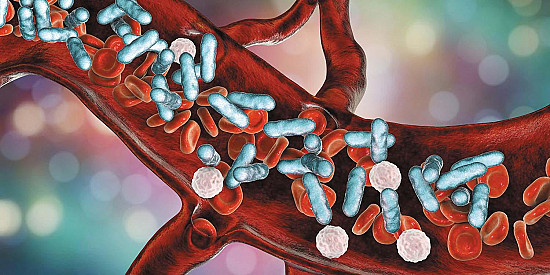

Once inside the body, HIV particles invade CD4 cells and use the cells' own building machinery and materials to produce billions of new HIV particles. These new particles cause the infected CD4 cells to burst (lyse). The new particles can then enter the bloodstream and infect other cells.

Once someone is infected with HIV, the number of their CD4 cells continues to decrease. HIV is actively copying itself and killing CD4 cells from the time the infection starts. Eventually, the number of CD4 cells drops below the threshold level needed to defend the body against infections, and the person develops AIDS.

Millions of people worldwide who have HIV don't know they are infected. It is important for people infected with HIV to know their status so they can get medical treatment before AIDS develops and they can take steps to prevent passing the virus to someone else.

Symptoms of HIV/AIDS

In its early stages, HIV infection often causes transient flu-like symptoms, such as fever, sore throat, rash, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, swollen lymph nodes, muscle aches, headaches, and joint pain. Doctors call this acute HIV infection.

The symptoms of acute HIV can be mild. So, the person or doctor may attribute the symptoms to a routine cold or flu. In a small number of cases, this early stage of infection may progress to meningitis (inflammation of membranes covering the brain) or severe flulike symptoms that require hospitalization.

Without treatment, the number of CD4 cells almost always declines. During this time, the person may begin to develop swollen lymph nodes and skin problems, such as varicella-zoster (shingles), seborrheic dermatitis (dandruff), new or worsening psoriasis, and minor infections. Ulcers can develop around the mouth and herpes outbreaks (oral or genital) may become more frequent.

Over the next few years, as more CD4 cells continue to die, skin problems and mouth ulcers develop more often. Many people develop diarrhea, fever, unexplained weight loss, joint and muscle pain, and fatigue. Old tuberculosis infections may reactivate even before AIDS develops. (Tuberculosis is one of the most common HIV/AIDS-related infections in the developing world.)

Finally, with further decreases in the levels of CD4 cells, the person develops AIDS. For an HIV-infected person, some signs that AIDS has developed (known as AIDS-defining conditions) are:

- The CD4 cell count has decreased to fewer than 200 cells per cubic milliliter of blood.

- An opportunistic infection has developed, indicating that the immune system is severely weakened. These types of infections include specific causes of pneumonia, diarrhea, eye infections and meningitis. Some of the causes of these opportunistic infections include Cryptococcus, reactivation of cytomegalovirus, reactivation of toxoplasma in the brain, wide-spread infection with Mycobacterium avium complex and Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly called Pneumocystis carinii) in the lungs.

- A type of cancer has developed that shows that the immune system is severely weakened. For those who are infected with HIV, these cancers can include advanced cervical cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma (a cancer causing round, reddish spots in the skin and mouth), certain types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and brain lymphoma.

- An AIDS-related brain illness has developed, including HIV encephalopathy (AIDS dementia) or progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) that is caused by the JC virus.

- There is severe body wasting (HIV wasting syndrome).

- There is an AIDS-related lung illness, such as pulmonary lymphoid hyperplasia or lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (usually seen only in children).

Diagnosing HIV/AIDS

Your doctor will ask about possible HIV risk factors, such as previous sexual partners, intravenous drug use, blood transfusion and occupational exposure to blood, such as accidentally being stuck by needles. Your doctor might ask about a variety of symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, muscle and joint aches, fatigue and headache, and about medical problems you may have had in the past like sexually transmitted infections or hepatitis.

This typically is followed by a complete physical examination. During the exam, your doctor will look for a thick, white coating on your tongue called thrush (infection with Candida), any skin abnormalities and swollen lymph nodes. To make the diagnosis of HIV infection, however, laboratory tests are needed.

Testing for HIV can be done in one of several ways. The most commonly used blood tests check the HIV antibody, the p24 antigen, and/or the HIV RNA viral load. These tests can detect the presence of infection within 7 to 14 days of exposure.

Expected duration of HIV/AIDS

HIV infection is a lifelong illness. There is no known cure for HIV. However, advances in treatment have changed the thinking about HIV as a fatal disease. Doctors now consider HIV a chronic condition that can be controlled with medications and healthy life style choices.

Preventing HIV/AIDS

HIV infection can be passed from person to person in any of the following ways:

- unprotected sexual intercourse (heterosexual or homosexual anal, vaginal or oral sex) with an infected person

- a contaminated transfusion (extremely rare in the United States since 1985, when blood products started being tested for HIV)

- needle sharing (if one intravenous drug user is infected)

- occupational exposure (needle stick with infected blood)

- artificial insemination with infected semen

- organ transplant taken from an HIV-infected donor

- newborns can catch HIV infection from their mothers before or during birth or through breastfeeding.

There is no evidence that HIV can be spread through the following: kissing; sharing food utensils, towels or bedding; swimming in pools; using toilet seats; using telephones; or having mosquito or other insect bites. Casual contact in the home, workplace or public spaces poses no risk of HIV transmission.

Although several HIV vaccines are being tested, none has been approved. You can decrease your chances of being infected with HIV by avoiding high-risk behaviors. To decrease the risk of HIV infection:

- Have sex with only one partner who is also committed to having sex with only you. Consider getting tested together for HIV.

- Use condoms with each act of sexual intercourse.

- If you use intravenous drugs or inject steroids, never share needles.

- If you are a health care worker, strictly follow universal precautions (the established infection-control procedures to avoid contact with bodily fluids).

- If you are a woman thinking about becoming pregnant, have a test for HIV beforehand, especially if you or your partner have a history of behaviors that could have put you at risk of HIV infection. Pregnant women who are HIV-positive need special prenatal care and medications to decrease the risk that HIV will pass to their newborn babies.

- If you believe you may have been exposed to HIV (through sexual contact or through exposure to blood, such as through a needle containing infected blood), medications may help prevent HIV infection before it takes hold in the body. The medication should be taken as soon as possible but not more than 72 hours (3 days) after exposure. If you think you may have been exposed, call your doctor or go directly for urgent care immediately.

For sexually active people who are HIV negative and have an increased risk of becoming infected with the virus, talk to your doctor about medication options for prevention.

Treating HIV/AIDS

Today, most experts recommend starting treatment immediately after the diagnosis is confirmed. But there may be individual circumstances why a person may choose to wait.

If the decision is made to start treatment, your doctor will choose a combination of drugs called antiretrovirals to fight your HIV infection. To control the reproduction of HIV in the body, several medications must be used together (often called a drug cocktail or highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). These medications attack HIV at multiple points in its growth cycle and are more effective in suppressing the virus. Combining drugs also limits the risk that HIV will become resistant to drugs, which would mean the drugs are powerless against this resistant strain of HIV.

Many studies have shown that people with high levels of virus in the blood (the viral load) will progress more rapidly to AIDS. Though it is not possible to clear the virus from the body completely, the goal of treatment is to keep the virus from reproducing. This can be seen when the viral load test cannot detected the HIV virus in the bloodstream (the virus never goes away, just goes to very low levels). When the virus is not reproducing quickly, it is less likely to kill CD4 cells. As the CD4 cell count increases, the immune system regains strength.

There are many available antiretroviral medications in the United States today. Many of these can be prescribed in combination form. Some have two or three names. They may be referred to by the generic name, trade name or a three letter abbreviation.

It is very important to tell your doctor about ALL other medications you take (including herbals and non-prescription medications) because there can be serious drug-drug interactions with commonly used medications. Also, no one should take an antiretroviral medication that was not specifically prescribed for them by a health care provider.

In addition to antiretrovirals, people with low CD4 counts often need to take drugs to prevent the development of opportunistic infections. For example, people with low CD4 cell counts could take trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or other medication to protect themselves against Pneumocystis pneumonia.

When to call a professional

Your doctor can help you protect yourself against HIV. Let your doctor know if you are a man who has sex with men or if you share needles with anyone for any reason (intravenous drugs or steroids, for example). If you are a woman and think your male partner may have risk factors for HIV infection, please let your doctor know. Your doctor can give you information about how to reduce your risk of HIV.

You should also speak with your doctor if you think you may already have HIV infection so that you can be tested for the disease. If you have long-lasting headache, cough, diarrhea, skin sores or are having fevers or losing weight, let your doctor know. Even without any symptoms, the sooner you get tested for HIV, the sooner appropriate treatment can be started than can help you live a long, healthy life.

Call your doctor immediately if you believe that you have been exposed to the body fluids of someone who has HIV or AIDS. If your exposure is felt to be significant, your doctor may recommend that you take antiretrovirals that may decrease your risk of getting HIV/AIDS. These drugs work best when they are taken within 72 hours (3 days) of the exposure.

Prognosis

Today, the life expectancy for many people with HIV is close to that of people that don't have the infection. The outlook is especially good for those who begin antiretrovirals at an early stage of the disease.

If you are infected with HIV, it is best to find out as soon as possible so that treatment can be started before the immune system is weakened. Since potent antiretrovirals became available in the United States, the number of AIDS-related deaths and hospitalizations has decreased dramatically.

Additional info

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

https://www.niaid.nih.gov/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

www.cdc.gov/

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.