How to get rid of warts

Getting rid of warts can be frustrating. But there are a range of options—both at-home and in the office— for relief.

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Warts are generally harmless and often disappear on their own over time, but they're unsightly. And some, like those found on the soles of the feet, can make walking and exercise painful. Wart removal can be a challenge, but fortunately, the most effective treatments are the least invasive.

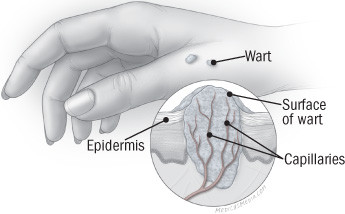

Wart anatomy

|

What do warts look like?

Warts grow in the epidermis, the upper skin layer. A typical wart has a raised, rough surface. (Some, like those on the face, may be smooth and flat.) The center of a wart may be flecked with dark dots; these are capillaries that supply it with blood.

What causes skin warts

Warts occur when skin cells grow faster than normal because they are infected with the human papillomavirus (HPV). Among the 150 strains of HPV, about 10 cause cutaneous (skin) warts, including common, plantar, and flat warts (see "Common types of skin warts," below).

All of us come into contact with HPV repeatedly — when we shake hands or touch a doorknob, for example — but only some of us develop warts, and that's hard to explain. Children and people with immune system abnormalities are particularly vulnerable. For reasons that aren't entirely clear, so are people in certain occupations, such as meat, fish, and poultry handlers. But the most likely explanation is that some people are simply more prone to warts than others.

Certain other HPV strains cause genital and anal warts. They are transmitted through sexual contact. Some specific types of HPV can cause cellular changes in the cervix and anus that can become cancerous. But the HPV strains that cause skin warts have rarely been linked to skin cancer.

Common types of skin warts |

||

|

Type |

Appearance |

Characteristics |

|

Common |

Raised, rough surface, sometimes with dark specks; light-colored to gray-brown. |

Found mostly on the hands, but may appear anywhere. Those under or around the fingernails and toenails can be hard to treat. |

|

Plantar |

Rough, spongy surface kept flat by walking; gray or brown with dark specks. |

Found only on the soles of the feet. Clustered plantar warts are called mosaic warts. |

|

Flat |

Flat or slightly raised; smooth and pink. Smaller than other warts. |

Found mostly on the face, hands, and shins. They're less common than other warts, but when they do appear, it's often in large numbers. |

How to treat skin warts

Studies indicate that about half of warts go away on their own within a year, and two-thirds within two years, so "watchful waiting" is definitely an option for new warts. But some experts recommend immediate treatment to reduce the amount of virus shed into nearby tissue and possibly lower the risk of recurrence. If you prefer not to wait it out, you have several treatment options:

At-home remedies for treating skin warts

- You can treat warts at home by applying salicylic acid, available without a prescription.

- Concentrations range from 17% to 40% (stronger concentrations should be used only for warts on thicker skin).

- Before applying the salicylic acid, be sure to soak the wart in warm water.

- File away the dead warty skin with an emery board or pumice stone, and apply the salicylic acid.

- Repeat the process daily or even twice a day.

- Salicylic acid is rarely painful. If the wart or the skin around the wart starts to feel sore, you should stop treatment for a short time.

- It can take many weeks of treatment to have good results, even when you do not stop treatment.

- Continuing treatment for a week or two after the wart goes away may help prevent recurrence.

Duct tape

- Low-risk, low-tech approach.

- You can leave the duct tape on overnight for about one month or until the wart is gone.

- Alternatively, keep the duct tape on for five to seven days, then remove it. You may need to repeat the cycle.

- Some studies suggest that silver duct tape works better because it is stickier.

- Why duct tape works isn't clear — it may deprive the wart of oxygen, or perhaps dead skin and viral particles are removed along with the tape.

- Some people apply salicylic acid before covering the wart with duct tape. But be very careful to only apply the salicylic acid on the wart itself and let if fully dry before putting tape over it.

In-office treatments for skin warts

Freezing

- Also called cryotherapy.

- A clinician swabs or sprays liquid nitrogen onto the wart and a small surrounding area. The extreme cold (which may be as low as –321 F) burns the skin, causing pain, redness, and usually a blister.

- Getting rid of the wart this way usually takes three or four treatments, one every two to three weeks; any more than that probably won't help.

- After the skin has healed, apply salicylic acid to encourage more skin to peel off.

- Some individual trials have found salicylic acid and cryotherapy to be equally effective, with cure rates of 50% to 70%, but there is some evidence that cryotherapy is particularly effective for hand warts.

Other agents

- Warts that don't respond to standard therapies may be treated with prescription drugs.

- The topical immunotherapy drug imiquimod (Aldara) may be used to treat skin warts. Imiquimod is thought to work by causing an allergic response and irritation at the site of the wart.

- In an approach called intralesional immunotherapy, the wart is injected with a skin-test antigen (such as for mumps or Candida) in people who have demonstrated an immune response to the antigen.

- Other agents that may be used to treat recalcitrant warts are the chemotherapy drugs fluorouracil (5-FU), applied as a cream; and bleomycin, which is injected into the wart.

- All these treatments have side effects, and the evidence for their effectiveness is limited.

Zapping and cutting

- The technical name for this treatment is electrodesiccation (or cautery) and curettage.

- Using local anesthesia, the clinician dries the wart with an electric needle and scrapes it away with a scooplike instrument called a curette.

- This usually causes scarring (so does removing the wart with a scalpel, another option).

- It's usually reserved for warts that don't respond to other treatments and should generally be avoided on the soles of the feet.

Ask your dermatologist if you are unsure about the best way to treat a wart.

Frequently asked questions

How do warts go away naturally?

The body's immune system fights the viruses that cause warts. Over time, the warts disappear on their own. Studies have found that warts in children and teenagers disappeared after one year in half of the cases. However, the amount of time it takes for warts to go away depends on the type of the virus, the type of wart, and the health of the person.

Are warts contagious?

Skin warts aren't highly contagious. They can spread from person to person by direct contact, mainly through breaks in the skin. Theoretically, you can also pick up warts from surfaces such as locker room floors or showers, but there's no way to know how often this occurs.

Warts on one part of the body can be spread to other areas, so it's important to wash your hands and anything that touches your warts, such as nail files or pumice stones.

A wart virus infection is different from a bacterial infection such as strep throat, which can be caught, treated, and eradicated because it progresses in a distinct, reliable pattern. The ways of warts are much less predictable.

The wart virus resides in the upper layer of the skin, and who knows where or when you picked it up? The virus could have been there for years. Then it makes a wart for reasons we don't understand. And when the wart goes away, you can still find the virus in the epidermis.

When to see your clinician

Some skin cancers resemble warts at first. If you have a wart that doesn't change much in size, color, or shape, you probably don't need to see a clinician. But if you're in your 50s and develop new warts, consult a dermatologist. Be suspicious of any wart that bleeds or grows quickly.

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.