The skinny on fatty liver

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is the most common liver disease. Here is what you should know about it.

- Reviewed by Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

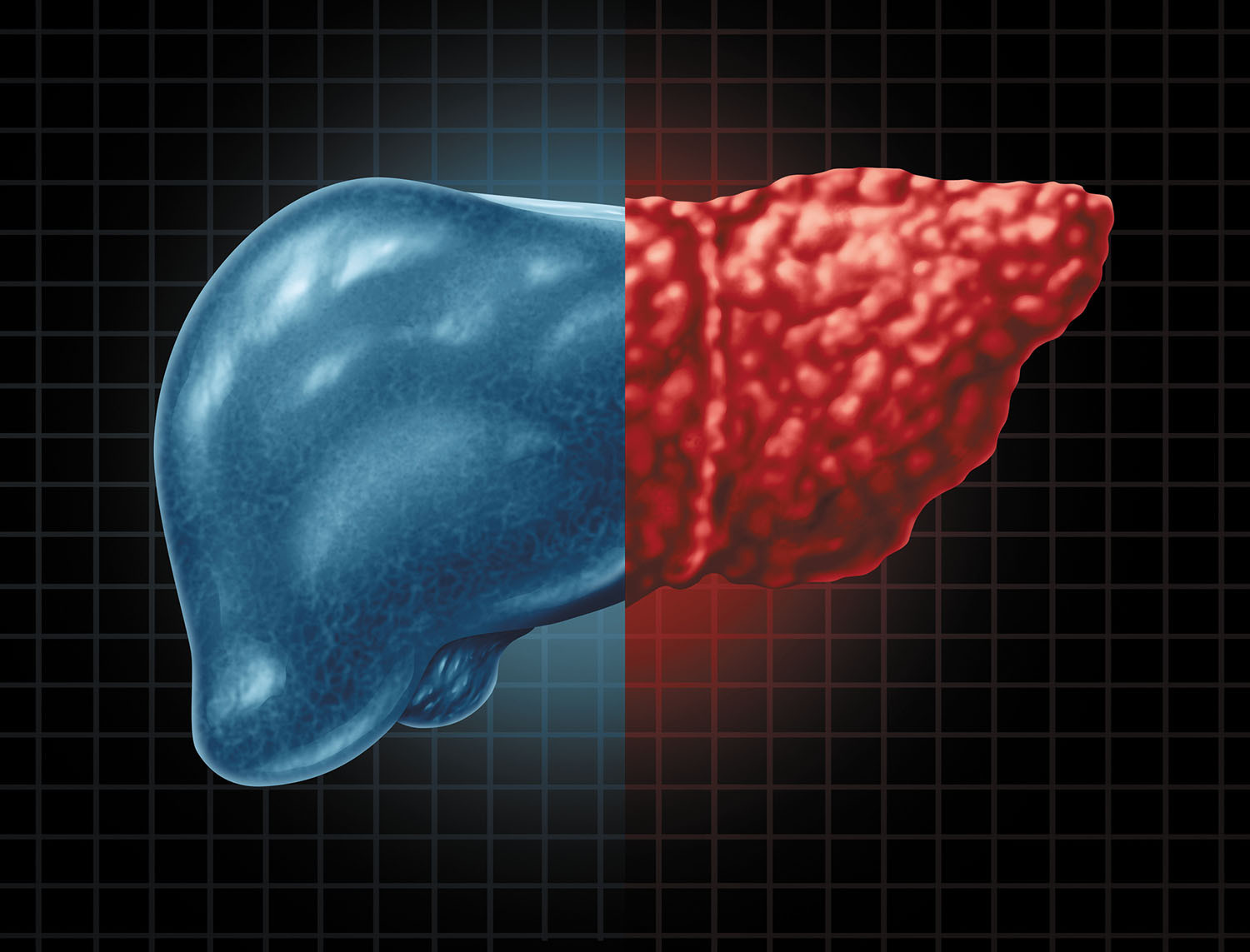

The liver is your body's largest internal organ. About the size of a football and weighing around 3 pounds, the liver performs more than 500 functions. Some of its daily tasks include producing cholesterol, creating bile to help digest fats, and filtering deadly toxins from the blood. (Also, the liver holds about a pint of your body's blood supply at any given moment.)

Despite its prowess, the liver is not invulnerable to illness. One of its greatest threats is nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the most common liver disease worldwide.

"NAFLD affects about 24% of U.S. adults, but most of them are unaware of the condition, in part because it rarely causes symptoms early on," says Dr. Howard LeWine, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief medical editor of Harvard Health Publishing.

Diabetes and obesity are the main risk factors for all forms of fatty liver disease. In fact, about 75% of people with one or both of these conditions have some form of NAFLD.

Types of NAFLD

NAFLD is an umbrella term that includes several forms of liver disease. Most people with NAFLD have a type known as simple fatty liver, or steatosis — excessive fat buildup in the liver not caused by overuse of alcohol, medication side effects, or genetic disease.

However, up to 20% of people with NAFLD develop inflammation in the liver known as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Left unchecked, this more dangerous form can progress into fibrosis (scarring) and potentially cirrhosis (severe scarring and liver damage).

"The exact reasons why some people progress to this inflammation stage is unknown," says Dr. LeWine. "However, an abnormally large waist size reflecting greater amounts of visceral fat — belly fat that surrounds our abdominal organs — appears to be an important risk factor."

Simple fatty liver and NASH are often detected not from the appearance of symptoms, but rather from an imaging test, such as an abdominal ultrasound or CT scan, conducted for another reason, like gallstones.

Other times routine blood work shows abnormal liver values, which usually means there is inflammation characteristic of NASH. But up to 50% of people with NASH have normal blood tests for liver function.

Primary care clinicians now have readily available, noninvasive ways to identify people at higher risk for NASH and early fibrosis. These include biomarker measurements and scoring systems based on blood tests (like the NAFLD fibrosis score and the Fibrosis-4 index). "The Fibrosis-4 index is a simple calculation based on common blood test results and a person's age," says Dr. LeWine. "The index provides guidance regarding treatment and when to refer to a liver specialist."

Another technology, called elastography, uses sound waves to estimate fibrosis based on the stiffness of the liver.

A weighty issue

There are no specific FDA-approved medicines for any stage of NAFLD. Therefore, lifestyle modifications are the best approach.

Because a majority of people with NAFLD are overweight or even obese, weight management is the No. 1 action people can take to avoid NAFLD and keep simple fatty liver from turning into NASH, says Dr. LeWine. Weight loss can also protect people from other health risks common in people with NAFLD, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and cardiovascular disease.

"Even men who are slightly overweight should be mindful about their weight, as any gradual increase can send them in the wrong direction and increase their risk for NAFLD," says Dr. LeWine.

If you are overweight, weight loss of roughly 5% of your body weight might be enough to decrease the fat in the liver. Losing between 7% and 10% of body weight can reduce the amount of inflammation and injury to liver cells, and it may even reverse some of the fibrosis. Target a gradual weight loss of 1 to 2 pounds per week. For people with diabetes and those unable to attain their goal weight, your doctor may recommend drugs known to induce weight loss, such as the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide (Wegovy).

Keep in mind that normal-weight people also can get NAFLD. "Where your body fat lies, especially around the belly, is also a strong indicator of NAFLD risk," says Dr. LeWine. One way to measure potential risk is waist size. "An ideal waist size for men is no more than half their height, so a six-foot man's waist should not exceed 36 inches," says Dr. LeWine.

What you eat, how you move

Although any diet that promotes weight loss helps NAFLD, a low-calorie Mediterranean-style diet is an excellent choice. This nutrition plan emphasizes fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and olive oil. Limit red meat; eat more fatty fish and lean poultry instead. While you're considering which foods to add to your diet, follow the motherly advice to eat your vegetables. A 2020 study found a link between eating a diet rich in cruciferous vegetables (such as kale, cauliflower, broccoli, and Brussels sprouts) and a reduced risk of NASH.

Drinking coffee also may offer some protection from NAFLD. Some studies have found an association between regular coffee consumption (about three to four daily cups) and a lower risk of progression from simple fatty liver to NASH and fibrosis.

Research shows that regular exercise, independent of weight loss, also can directly help prevent and manage NAFLD. An analysis in the October 2021 issue of Frontiers in Nutrition found that exercise can reduce fat throughout the body, and especially visceral fat, the more dangerous deep layer of fat associated with liver inflammation.

Research suggests that both aerobic and anaerobic exercise (like high-intensity interval training and strength training) are good for people with NAFLD. One study found that 20 to 60 minutes of moderate aerobic and anaerobic exercise, done three to four days per week, helped reduce liver fat and reverse liver damage in NASH patients.

Image: © wildpixel/Getty Images

About the Author

Matthew Solan, Executive Editor, Harvard Men's Health Watch

About the Reviewer

Howard E. LeWine, MD, Chief Medical Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.