A daily drink: Not as harmless as you might think

Contrary to popular belief, even modest amounts of alcohol may raise heart disease risk.

- Reviewed by Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

In recent years, the long-held notion that alcohol is good for your heart has slowly started to dry up. Now, a new study suggests that any amount of alcohol — even just one drink per day — may raise rather than lower a person's risk of cardiovascular disease.

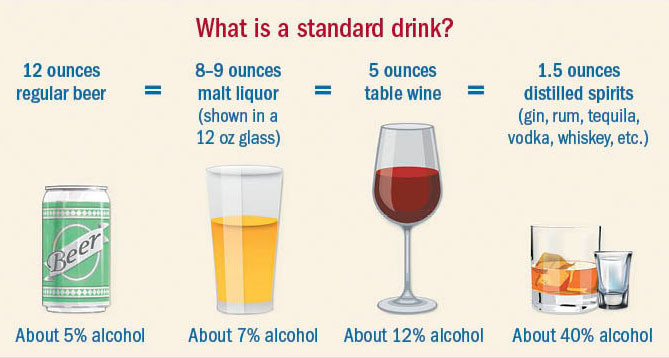

"We found that along the entire spectrum of alcohol consumption, the risk of high blood pressure and coronary artery disease increases rather than decreases," says Dr. Krishna Aragam, a cardiologist at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital and the study's lead author. But the amount matters quite a bit, he says. If you have up to seven drinks per week, the added risk to your heart appears to be minimal. If you go above that amount, however, the risk rises exponentially (see "What is a standard drink?").

Observational studies dating back to the early 1990s linked light to moderate drinking (one to two drinks per day) to a lower risk of heart disease. But such studies can't prove that alcohol was responsible for the benefit. Light to moderate drinkers tend to be well educated, fairly affluent, and likely to have healthy lifestyle habits, all of which may explain their lower risk. Researchers can attempt to control for these so-called confounding factors, but it's tricky to capture all the possible influences.

What is a standard drink?

All of the above drinks contain about the same amount of alcohol, despite their different sizes. Each counts as a single or standard drink. Depending on the recipe, a mixed drink may contain one, two, or more standard drinks, as shown in a cocktail content calculator from the National Institutes of Health (see /cocktail). Source: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIH. |

Genetic variants and drinking habits

The new study, published March 25, 2022, in JAMA Network Open, included data on nearly 400,000 people from UK Biobank, a large database of health and genetic information in the United Kingdom. The participants, whose average age was 57, reported consuming 9.2 drinks per week on average. Because the study was so large, the scientists were able to estimate the added risk at different levels of alcohol consumption.

As shown in earlier studies, light to moderate drinking went hand in hand with a lower risk of heart disease. But after the researchers adjusted for just six factors associated with heart health (smoking, physical activity, body mass index, red meat consumption, cooked vegetable intake, and self-reported health), the "benefit" nearly disappeared.

But Dr. Aragam and his colleagues went a step further. They also looked at specific genetic variants that track closely with how much alcohol a person drinks. These variants are unlikely to be related to other lifestyle factors and occur randomly within the population. The researchers found that people with genetic variants that predicted higher alcohol consumption did indeed drink more and were also more likely to have high blood pressure and coronary artery disease.

It's important to note that the risk assessed in this study pertains to the first-time diagnosis of a heart-related issue. "The risk from alcohol may be even greater for people who already have cardiovascular disease, although this study doesn't address that question," says Dr. Aragam. Moreover, there's compelling scientific evidence that for people with atrial fibrillation, cutting back on alcohol clearly reduces episodes of the rapid, irregular heart rate that characterizes the disorder.

Lower limits?

Currently, the federal dietary guidelines suggest that if you drink, you should limit yourself to fewer than 15 drinks per week if you're male and eight if you're female. But the new data suggest that men should stick to the lower limit as well — a suggestion that was initially considered but ultimately rejected during the last update of the guidelines.

"I'm now telling my patients that if you have up to seven drinks per week, your risk of heart disease does not decrease but instead will increase," says Dr. Aragam. Because the added risk is minimal, however, cutting back isn't necessarily a big priority. "People can only focus on so much at a time, so if I have a patient who smokes, is overweight, and has one drink per day, I'd prioritize stopping smoking and losing weight over cutting back on alcohol," he says.

But for patients who regularly have more than one drink per day, it's a different conversation. "I make it clear that no amount of alcohol is good for you. But if you can cut down to one drink instead of two to three per day, you'll get most of the benefit right there," says Dr. Aragam.

Advice for cutting back

To cut back on your drinking, these tips may help:

- Keep a drinking journal. Write down what and how much you drink for a few weeks to get a better sense of how much you imbibe.

- Don't keep any alcohol (or keep just limited amounts) in your house. Doing so can limit your drinking to social occasions or restaurants and may discourage you from drinking simply out of habit.

- Dilute and sip slowly. Dilute your wine or cocktail with sparkling water and ice. Take your time drinking it.

- Establish alcohol-free days. Choose several days each week to steer clear of all alcohol.

Image: © Jose Luis Pelaez Inc/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.