Addressing language challenges after a stroke

With persistent effort and help from assistive tools, stroke survivors can continue to improve their ability to communicate even years after a stroke.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Last November, John Fetterman won the election for the open U.S. Senate seat in Pennsylvania just six months after experiencing a stroke that left him with auditory processing issues. During interviews and debates, Fetterman used closed captioning, one of several technologies that can help people cope with language-based disorders, known collectively as aphasia.

Aphasia — which can range from mild to severe — may affect just one or several aspects of language processing, including speaking, understanding, reading, and writing (see "Types of aphasia"). Although different types of brain injuries and conditions can cause aphasia, stroke is the most common. Of the nearly 800,000 people in the United States who have a stroke each year, around 30% will experience aphasia.

But through a process called neuroplasticity, the brain has the ability to rewire brain cells (neurons) and recover lost function, says Dr. Randie Black-Schaffer, chief of the Division of Stroke and Neurology in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation of Harvard Medical School. "Neuroplasticity is greatest in the first several months after a stroke. But people who've had a stroke who keep working on their language processing problems can continue to improve for years," she says.

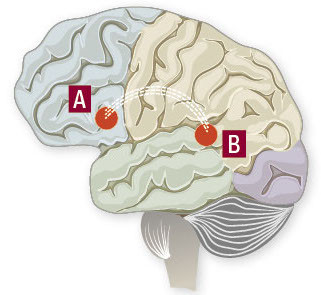

Types of aphasia

Aphasia results from injury to specific parts of the brain responsible for expressing and understanding language. Most often, an ischemic stroke (the type caused by a blood clot) in the left side of the brain is to blame. The location of the clot and the extent of the resulting damage dictates the type and severity of aphasia a person has. There are three main types: Expressive aphasia (A). Also known as Broca's aphasia, this comes from damage in a part of the frontal lobe. This area is in charge of arranging words in sentences and translating meaning into sounds. People understand what others are saying and know what they want to say, but they struggle to get the words out. Receptive aphasia (B). Also called Wernicke's aphasia, this results from damage in part of the temporal lobe that connects information about word meanings with the speech output centers in Broca's area. People can often speak fluently but don't always make sense, and they also have difficulty understanding what others are saying. Global aphasia. This type of aphasia occurs when a stroke causes extensive damage in both the front and back regions of the left half of the brain. |

Speech and language therapy

Many rehabilitation centers have comprehensive aphasia programs that are designed to treat people a year or more after a stroke. In one-on-one sessions with a speech-language pathologist, people practice repeating words, naming things and people, and reading and writing. A framework known as the life participation approach to aphasia uses a variety of methods, techniques, and tools to help people more fully engage in their lives, says speech-language pathologist Lynne Brady Wagner, associate director of the Harvard-affiliated Spaulding Stroke Wellness Institute. "One example is having a note, either on a wallet card or your smartphone, that includes basic information about your specific limitations and ways people can help — for example, speaking slowly and using gestures," says Brady Wagner. The closed captioning Fetterman used can help with forms of receptive aphasia, while people with expressive aphasia might use a speech-generating device.

Telerehabilitation and other resources

Health insurance usually covers only a limited number of post-stroke language rehabilitation sessions, so people pay out-of-pocket for extended therapy. During the COVID-19 epidemic, many sessions shifted to virtual visits, says Dr. Black-Schaffer. If these online visits can continue, it would be a huge boon, especially for people who don't live close to a rehabilitation center or whose strokes have left them with mobility problems, she adds.

People with aphasia may also be able to take advantage of other options, such as local in-person or online community support groups. Many colleges and universities have accredited speech and language programs. "Those with on-site graduate student clinics can provide continued interactive therapy for people with aphasia, which are provided either pro bono or on a sliding fee scale," says Brady Wagner. Finally, people can also use specialized apps designed to help people practice language skills. The National Aphasia Association (www.aphasia.org) provides a list of these apps (look under the "Resources" tab) in addition to other useful information.

Image: © ttsz/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.