Aortic valve replacement options

Ask the doctor

Q.

My 60-year-old sister recently had open heart surgery to replace her aortic valve. It turns out that she had a bicuspid valve that was severely narrowed. But why couldn't she have the other, less invasive procedure, which I heard has a much shorter and easier recovery?

Q.

My 60-year-old sister recently had open heart surgery to replace her aortic valve. It turns out that she had a bicuspid valve that was severely narrowed. But why couldn't she have the other, less invasive procedure, which I heard has a much shorter and easier recovery?

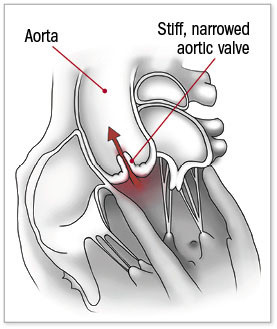

A. Narrowing of the aortic valve develops when calcium deposits build up on the flaps of tissue (called leaflets) that regulate blood flow through the valve (see illustration). Known as aortic stenosis, this can cause shortness of breath, chest pain, and dizziness. Most people who develop severe aortic stenosis are in their 70s and 80s. But the problem can occur much earlier in people with a bicuspid aortic valve, which means the valve has only two leaflets instead of the normal three. Between one and two of every 100 people is born with this defect.

Until recently, open heart surgery was the only way to replace a failing aortic valve. But in 2011, the FDA approved transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR), which delivers a new valve to the heart through a slender tube (catheter) that's inserted through an artery at the top of the thigh. This procedure — which doesn't even require general anesthesia — does indeed have a shorter, easier recovery. Most people can go home the next day or even the same day, compared with about a week in the hospital after the traditional surgery. By 2020, more people who needed a new aortic valve underwent TAVR than had open surgery.

Unfortunately, most people under age 65 with aortic stenosis and a bicuspid aortic valve need open heart surgery instead of TAVR. As my interventional cardiologist colleague Dr. Pinak Shah explains, the anatomy of a bicuspid valve can make TAVR more challenging, which could increase the likelihood of complications. In addition, about half of people with a bicuspid valve also have an aneurysm (swelling due to a weakened vessel wall) in the aorta near the heart. Larger aneurysms at risk of rupturing could potentially be repaired during the same open heart surgery. To date, most clinical trials of TAVR haven't included people with bicuspid valves.

Your sister's age is relevant for another reason. Both traditional surgery and TAVR use valves taken from cows or pigs. But the valves eventually wear out, lasting about 15 years, on average. So it's quite possible she may require another valve replacement during her lifetime. While a TAVR after a surgical replacement seems feasible, we know less about the durability and best way to treat someone who received a valve via TAVR that requires a replacement.

Finally, all of her close family members (you and any other siblings, your parents, and any children she has) should get an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound) to check for a bicuspid aortic valve, as this condition runs in families.

Illustration by Galiya Kolnsberg

About the Author

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.