Coronary microvascular disease: Trouble from tiny vessels

Thanks to the growing use of specialized diagnostic tools, this stealth condition is becoming more widely recognized.

- Reviewed by Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

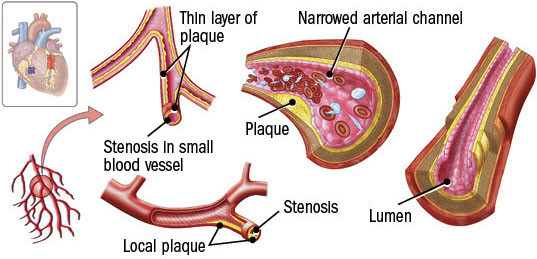

The squeezing chest discomfort known as angina happens when heart muscle cells don't get enough oxygen-rich blood. Much of the time, the underlying cause is a buildup of fatty plaque inside the heart's largest arteries that restricts normal blood flow. But sometimes, angina arises from problems in the network of tiny blood vessels in the heart — a condition called coronary microvascular disease.

Doctors suspect microvascular disease in people with angina who have no evidence of artery narrowing on coronary angiography. This test, which uses dye and x-rays, shows only the outline of the lumen, the inner channel of the arteries (see illustration). "But the resolution isn't high enough to visualize the smaller vessels, where most of the resistance to blood flow occurs," says Dr. Viviany Taqueti, who directs the cardiac stress laboratory at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. These tiny vessels — some no wider than a few human hairs — regulate blood flow to match the heart tissue's changing needs.

"We now recognize that up to 50% of people undergoing coronary angiography have no evidence of flow-limiting plaque in their arteries," says Dr. Taqueti. Yet many still experience symptoms of angina, typically during exercise or mental stress. Back in the early 1970s, this puzzling phenomenon was dubbed "cardiac syndrome X" because doctors didn't understand the cause. Today, cardiologists refer to the condition as INOCA: ischemia (which refers to inadequate blood flow) with non-obstructive coronary arteries. For unknown reasons, INOCA is more common in women than men, although microvascular disease can affect both sexes.

Coronary microvascular disease

Coronary microvascular disease affects the heart's tiny vessels, some of which are no wider than a few human hairs. |

Tiny vessel problems

INOCA comes in two main forms. In the most common, microvascular angina, the inner walls of smaller arteries may thicken and lose their ability to expand and contract in response to the demand for increased blood flow, such as during exercise. In addition, the sheer number and total volume of capillaries (the tiniest vessels) are lower in people with microvascular disease compared with people who don't have the disease.

The other, less common type is vasospastic angina. Muscles within the heart's arteries suddenly clamp down, causing a coronary spasm. These brief, temporary spasms block blood flow to heart muscle. Some people have both types together, says Dr. Taqueti.

Although the affected arteries may be small, the symptoms can have a big impact on a person's quality of life. Similar to those caused by obstructive coronary artery disease, the symptoms can include shortness of breath or trouble exercising. INOCA can also increase a person's risk of hospitalization for a heart attack, heart failure, and death.

Diagnosis challenges

Diagnosing coronary microvascular disease requires more specialized testing than what's typically done in people with suspected heart disease. A coronary flow reserve (CFR) test measures how well the heart's circulation can deliver blood under stress versus at rest. It can be done by placing a wire in the heart's main arteries and administering a drug that dilates blood vessels and mimics the effects of exercise.

But CFR can also be measured noninvasively with a nuclear stress test involving PET scans (see "What to expect during an exercise stress test" in the November 2018 Heart Letter). PET scans rely on an injection of a radioactive tracer to quantify blood flow into the heart muscle, both at rest and following stress.

An accurate diagnosis can help doctors to better tailor treatment strategies, says Dr. Taqueti. People with coronary microvascular angina may benefit from therapy that includes beta blockers, while those with vasospastic disease may benefit more from calcium-channel blockers. Clarifying the diagnosis is also important to better define the condition and develop novel, targeted therapies, she adds.

Additional advice

The same factors that contribute to blockages in larger arteries, such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, and smoking, are also common in people with microvascular disease. As a result, many people with coronary microvascular disease also receive other common heart drugs, such as cholesterol-lowering statins. High blood sugar, the hallmark of diabetes, seems to be especially damaging to tiny vessels. Lifestyle and medication changes to improve heart disease risk factors may be beneficial. While there aren't any therapies yet that specifically target coronary microvascular dysfunction, it's a growing area of interest and research, says Dr. Taqueti.

Image: © Stocktrek Images/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.