Deep-vein blood clots: Are you at risk?

This dangerous problem is more common in older people and those with certain medical conditions.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

If you cut or scrape your skin, blood clots come to the rescue to stop the bleeding. But clots that stop blood flow inside your body are a different story. If a clot blocks an artery supplying the heart or brain, it can trigger a heart attack or stroke.

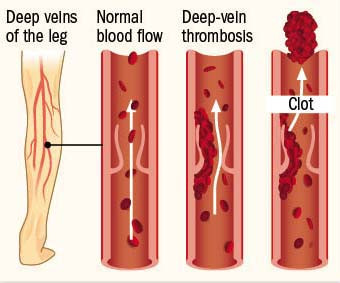

Clots can also form inside the veins, leading to a less familiar problem called venous thromboembolism. Most often, venous clots develop deep inside the leg, a condition known as deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). A more serious threat occurs if a clot breaks free and travels to one of the lungs, causing a pulmonary embolism (PE).

Every year, an estimated 600,000 people in the United States have a DVT, and about 400,000 have a PE. But many people aren't aware of the symptoms (see "Symptoms of venous thromboembolism") or the potentially serious nature of venous clots.

Deep-vein thrombosis

A deep-vein thrombosis is a dangerous clot that develops in the body, usually the leg. Image: © solar22/Getty Images |

Who is at risk?

"In addition to recognizing the signs and symptoms of DVT, it's important to know that there are certain conditions and situations that put people at higher risk," says Dr. Behnood Bikdeli, a cardiologist at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. Anyone can develop a venous clot, but the risk rises with age. These are some other factors that leave people more vulnerable to a DVT:

Decreased blood flow. The underlying reason is usually inactivity due to extended bed rest, prolonged travel (five hours or longer ), paralysis, or stroke.

Hospitalization. Being hospitalized for any reason raises your risk.

Recent major surgery. Clot risk remains high at least 30 days following a surgery such as a joint replacement, heart surgery, or hysterectomy.

Major trauma or injury. This might be a serious car accident, a broken bone, or a severe muscle injury.

Chronic medical conditions. These include obesity, varicose veins, heart failure, cancer, lung disease, kidney disease, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Increased estrogen. Pregnancy or the use of birth control pills or hormone therapy (especially estrogen therapy) increases risk.

Clotting disorder. Between 5% and 8% of people have one of several inherited disorders that make them more likely to develop clots.

A COVID-19 infection (especially one that requires hospitalization) also leaves people more prone to venous thromboembolism, says Dr. Bikdeli. While some of the risk comes from being bedridden, COVID-19 in particular tends to promote inflammation, which encourages clot formation.

Symptoms of venous thromboembolismDeep-vein thrombosis: These clots usually develop in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis but occasionally the arm. The affected area may be

If these symptoms linger for more than a few hours, call your doctor for advice. Do not rub or squeeze the affected area. Pulmonary embolism: Symptoms may include

If you have these symptoms — especially if they worsen quickly over a period of hours or persist — call 911 right away. |

Diagnosing and treating clots

Testing may include a blood test for D-dimer, a protein fragment that forms as a byproduct of clot breakdown. Levels are often elevated in people with DVT or PE. People with low levels and no predisposing conditions may not need further testing. Imaging tests, such as ultrasonography of the veins, can confirm a DVT, while a person with a suspected PE will need a CT or other specialized scan.

Treatment usually includes anti-clotting drugs such as apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto); very sick people may need injectable clot-preventing medications such as heparin. People usually stay on the oral drugs for several months and sometimes longer, especially if they have chronic health conditions that contribute to their risk, says Dr. Bikdeli. If that's the case for you, find a clinician who can give you targeted advice about preventing future clots with respect to exercise, travel, and any future surgeries, he suggests.

If you have to sit for long stretches, the following tips may help prevent DVT:

- Walk around every hour or two.

- Flex and extend your ankles and knees every once in a while.

- Avoid crossing your legs.

- Change positions often while seated.

Stay well hydrated by drinking plenty of water.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.