Get a leg up to avoid complications from PAD

Regular walking is the best treatment for clogged leg arteries, a condition called peripheral artery disease (PAD).

- Reviewed by Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

If you notice a crampy, painful sensation in one of both of your legs when you walk, don't automatically dismiss it as overexertion or aging. It could be peripheral artery disease (PAD), which happens when fatty deposits collect in arteries beyond the brain and heart — most commonly in the legs — and reduce blood flow to that area.

An estimated one in 10 people over age 55 has lower-extremity PAD. The same factors that cause plaque buildup in the heart arteries (coronary artery disease) also result in plaque deposits in the lower-extremity arteries: older age, smoking, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and diabetes.

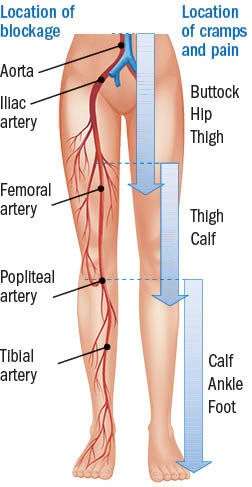

Doctors refer to the classic pain of PAD as claudication (from a Latin word meaning "to limp"). The pain usually occurs in the calf but may also strike the thigh, hip, or buttocks and goes away during rest. "Sometimes people don't notice the pain until they're a mile into a walk. But some of my patients tell me that their pain starts even before they reach their mailbox," says Dr. Anahita Dua, who co-directs the Peripheral Artery Disease Center at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital.

PAD blockages and symptoms

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) refers to blockages in arteries outside the heart, most commonly in the legs. Image: © Nicole Wall/Getty Images |

Other symptoms and complications

Although smoking is the biggest risk factor for PAD, having diabetes is also worrisome. Diabetes tends to weaken and damage blood vessels. If not well controlled, diabetes may lead to peripheral neuropathy, which causes numbness in the hands and feet. As a result, pain from PAD may go unrecognized.

In some cases, people with PAD notice other changes, such as coldness or discoloration in one or both feet, slow-healing foot sores, or slow growth of leg hair or toenails. All are signs of poor circulation to the foot and may signal a more serious condition called critical limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) which, if left untreated, may lead to amputation. CLTI requires immediate treatment with an artery-opening procedure to restore blood flow (angioplasty and stenting or bypass surgery).

But people can sidestep that dire fate with early identification. To test for PAD, doctors use a test called the ankle-brachial index, which compares the blood pressure in your arm to the blood pressure in your ankle. If your arteries are clear, the two readings should be fairly similar. Lower pressure in the ankle suggests PAD. You also may need an ultrasound and other tests.

Preventing PAD

The same lifestyle advice for preventing heart attacks also applies for PAD: quit smoking, follow a healthy diet, and get regular exercise. For people with claudication, walking is by far the best way to slow the progression of PAD and reduce its complications, Dr. Dua says. That might sound counterintuitive because of our natural urge to avoid pain, but the temporary discomfort pays off over the long term.

Walking encourages blood flow in the leg's smaller arteries and also creates new channels that move blood around the blocked areas, which eventually helps ease the pain. "Think of it like a highway closure, but then the cops set up multiple detours to move traffic on smaller roads around the obstruction. Over time, the traffic flow will be the same as if the original highway was reopened," says Dr. Dua.

People with PAD should walk for at least 30 minutes at least three times a week. Make sure to walk continuously until you feel leg pain, rest until it subsides, and then continue. "Over time, you'll be able to walk farther and farther before the pain sets in," Dr. Dua says.

Supervised exercise therapy (done on a treadmill or in any place that allows for continuous walking) is overseen by an exercise therapist or nurse and has proven benefits for people with PAD. But even though Medicare has covered this therapy since mid 2017, it's not widely available and is rarely used. Evidence for the benefits of home-based walking programs is growing. However, these involve check-ins with physical therapists or other health professionals who provide coaching, advice, and support, and it may be hard to get access to this service.

Another potentially promising option is a smartphone app that helps people with PAD keep tabs on their walking progress and provides coaching and education. According to the Society of Vascular Surgery, the app is still being tested and validated but may be available in the near future.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.