Novel procedure may lower stubbornly high blood pressure

Called renal denervation, the technique targets overactive nerves that supply the kidneys. Who might benefit from this yet-to-be-approved procedure?

- Reviewed by Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Poorly controlled blood pressure remains a serious problem in the United States. According to the American Heart Association, about one-third of heart-related emergency department visits can be blamed on high blood pressure. Defined as a blood pressure reading of 130/80 or higher, high blood pressure is the leading cause of heart attack and stroke.

Yet only about a quarter of people with high blood pressure (also known as hypertension) have the condition under control. Why? Often, people don't take blood pressure medications exactly as prescribed — they skip some or even all of the doses. But about one in seven people has what's known as resistant hypertension, defined as having high blood pressure despite taking three or more blood pressure medications, including a diuretic.

Both problems helped inspire the development of a new, nondrug approach to lower blood pressure. Enter renal denervation — a minimally invasive procedure that destroys some of the nerves surrounding the renal arteries that supply the kidneys. "The idea is to disrupt the communication between the brain and kidneys that leads to high blood pressure," says Dr. Randall Zusman, director of the Division of Hypertension at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital. The exact mechanism isn't fully understood. But people who undergo the procedure are still able to raise their heart rate and blood pressure when needed, he says.

5 habits to lower blood pressureThese nondrug approaches can help lower your blood pressure.

|

What is renal denervation?

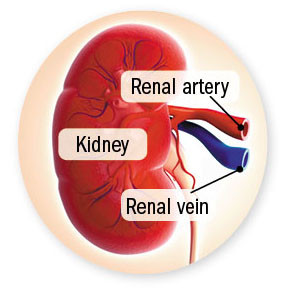

For the procedure, a physician guides a thin, flexible catheter into a small incision in the top of the thigh or at the wrist and threads it through the blood vessels to the renal artery (see illustration). "The nerves that control the kidneys run inside the wall of the renal arteries," says Dr. Zusman. A tiny device at the catheter's tip disables some of these nerves using either radiofrequency energy, ultrasound, or alcohol, explains Dr. Zusman, who has been involved in clinical trials or served as a consultant with companies using each of these three different approaches.

The renal arteries leading to both kidneys are treated. The procedure is done under conscious sedation (you're drowsy and relaxed but may feel some pain) and takes about 30 minutes.

Ups and downs of denervation

The history of renal denervation dates back to the early 1950s, when doctors tried disrupting brain-kidney communication with a procedure that severed the nervous system connections in the neck or chest to treat very high blood pressure. But this approach was quickly abandoned because it led to dangerously low blood pressure. The current catheter-based strategies using radiofrequency energy were developed in the 1990s, and the initial results looked very promising.

To prove its actual worth, however, researchers had to compare renal denervation to a placebo — in this case, a sham procedure that involved placing the catheter but without delivering the treatment. In an early trial in 2014, renal denervation proved no more effective than a sham procedure. However, subsequent studies using a variety of different devices suggest the procedure can consistently and significantly lower blood pressure. The trials have included a wide spectrum of people, from those with resistant hypertension who continued taking medication to those who had not yet taken any blood pressure drugs.

Varied responses

"What's particularly interesting is that while some people experience dramatic reductions in blood pressure after renal denervation, others have very little or no response," says Dr. Zusman. Right now, we don't know how to identify who will benefit the most, so that's an area of continued research and interest, he says. While the procedure can produce some side effects, including bruising and bleeding where the catheter is inserted, these tend to be minor and uncommon. Currently, renal denervation is available in some European countries. In the United States, two medical device companies are in the process of applying for FDA approval for their catheter devices.

Image: © Shubhangi Ganeshrao Kene/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.