The lowdown on a low heart rate

Known as bradycardia, this heart rhythm disorder can cause fatigue, dizziness, and fainting.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

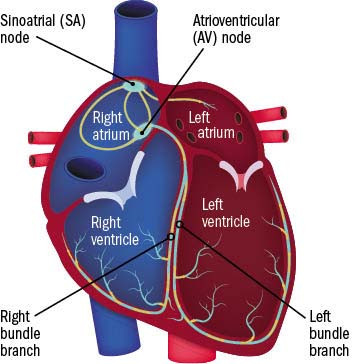

The steady beat of your heart depends on a tiny cluster of cells located in the upper right chamber of your heart. Known as the sinoatrial node or sinus node, these cells generate a tiny jolt of electricity that triggers the heart to contract and pump blood throughout the body. Because the sinus node sets the heart's pace and rhythm, it's often referred to as the body's natural pacemaker. But several "backup generators" elsewhere in the heart can keep this vital system functioning (see illustration).

A normal heart rate ranges between 60 and 100 beats per minute (bpm), although it may drop as low as 40 during deep sleep. A heart rate below 60 bpm during the day is considered a low heart rate, or what doctors call bradycardia.

If your heart rate is low and you don't have any symptoms, there's no reason to worry. But if you do have symptoms — such as feeling dizzy, lightheaded, fatigued, breathless, or confused, or if you faint — seek medical care right away. Here's the lowdown on the possible causes of bradycardia and how it's diagnosed and treated.

The heart's electrical conduction system

The sinoatrial (SA) node emits tiny electrical impulses that signal the atria to contract, filling the ventricles with blood. The atrioventricular (AV) node, located between the right atrium and ventricles, conducts the electrical signal from the atria to the ventricles. The ventricles then contract, pumping blood into the circulation. A low heart rate (bradycardia) can occur if the SA node falters. When that happens, the AV node takes over and maintains a heart rate of about 50 to 60 beats per minute. If the electrical signals passing through this area are slowed or blocked, it's known as AV block or heart block. Next in the conduction pathway are the left and right bundle branches, which are the final signals telling the ventricles to contract. If all those backups fail, the heart muscle may still contract, but only about 20 to 40 beats per minute — too slow to provide enough blood to the brain. Image: © Rujirat Boonyong/Getty Images |

What causes a low heart rate?

"The most common cause of bradycardia is age-related degenerative changes in the heart's conduction system," says Dr. Matthew Yuyun, a cardiologist at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. Just as your skin, joints, and other parts of your body reveal signs of wear and tear as you age, so too can the structures inside your heart. It's why bradycardia that requires treatment is more common in older adults, usually after age 70.

Other heart-related issues can leave people more prone to bradycardia. They include a previous heart attack, heart failure, a heart procedure (such as bypass surgery or a valve replacement), or heart inflammation caused by an infection, says Dr. Yuyun. One example is Lyme disease, a tick-borne infection common in New England that, if left untreated, can infiltrate heart tissue and interfere with electrical signals.

Other problems that can cause bradycardia include

- repeated breathing pauses during sleep (obstructive sleep apnea)

- low thyroid function (hypothyroidism)

- an imbalance of minerals in the blood, such as potassium or calcium

- certain medications, such as blood pressure drugs (especially beta blockers), sedatives, and opioids

- diseases such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, and hemochromatosis.

However, in athletes and very physically active people, a low heart rate, even down to 45 bpm, is perfectly normal. "Regular exercise makes the heart stronger and more efficient," says Dr. Yuyun. Because each beat delivers more blood to the body, the heart doesn't need to beat as quickly, he adds.

Diagnosis and treatment

Because episodes of bradycardia may come and go, a brief measurement of the heart's electrical activity (an electrocardiogram) may not pick up the problem. Instead, people often need to wear a portable heart monitor that records the heart's rate and rhythm for at least a day and sometimes several weeks.

Treatment depends on the cause and severity. Addressing the underlying condition or adjusting medications some-times helps. In other cases, people need a pacemaker, a small battery-powered device that sends pulses of electricity through wires to your heart.

Irreversible damage to the heart's electrical system requires a permanent pacemaker. These devices, which are placed during a minor surgical procedure, are programmed to stimulate your heart as needed to keep it beating normally. Most are implanted under the skin in the upper chest, but some people receive a tiny wireless device the size of a vitamin pill that is inserted in the right side of the heart.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.