Understanding aneurysms

What you need to know about these uncommon but much-feared blood vessel abnormalities.

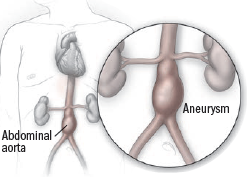

Each year, tens of thousands of people discover they have a bulging blood vessel in their brain, chest, or abdomen. Known as aneurysms, these bulges or balloon-like pouches form at a weak spot along an artery. The most common — and most dangerous — are in the brain or along the body's largest blood vessel, the aorta (see illustration).

Because aneurysms are uncommon, doctors don't screen for them routinely. Most are found by accident during tests such as an ultrasound or MRI scan done for other reasons. Of course, some aren't discovered until they leak or burst, often without any warning signs. The potentially fatal consequences of that bleeding explain why most people associate aneurysms with a sense of dread. However, understanding the underlying causes can help you prevent them and know whether you should undergo any screening tests.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

The abdominal aorta is one common location for an aneurysm, but one can also form at the top of the heart or in the brain. |

Acquired vs. inherited

With all aneurysms, the common underlying phenomenon is a weakness in an artery wall. That weakness may be acquired or inherited, and both the causes and consequences vary with the location of the artery.

In the aorta, for example, a buildup of fatty plaque can damage the integrity of the vessel wall. As the main conduit out of the heart, the aorta is a very high-pressure environment, so any vulnerable areas will gradually expand. Most aortic aneurysms occur in the abdomen, but about a quarter form in the chest. Smoking, high cholesterol, and other cardiovascular risk factors will increase your odds of developing one.

In contrast, the brain's arteries are prone to weakness from a different cause. These arteries are like a series of pipes that are fused together. Sometimes, the connection points where the arteries branch fuse incompletely, creating a weak area. Certain inherited conditions that compromise the body's connective tissue or blood vessel formation leave people more vulnerable to having these weak areas. Both high blood pressure and smoking can further weaken the vessel over time, making a brain aneurysm more likely.

In fact, these inherited conditions, which include vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and fibromuscular dysplasia, can also increase the risk of an aortic aneurysm.

Here's more detail about the three major locations of aneurysms:

Cerebral (brain) aneurysm. An estimated 10 to 15 million people in the United States have a brain aneurysm, based on findings from imaging studies and autopsies. But most people will live their entire lives never knowing they have one and will die of something unrelated. Only about 30,000 rupture each year, with most ruptures occurring in people over age 50. The classic symptom is a sudden, severe headache; others include loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, and seizures. Anyone with two or more first-degree relatives (a parent, sibling, or child) with a brain aneurysm should be screened starting at age 20.

Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Between 2% and 8% of adults have abdominal aortic aneurysms, but they are most common among older male smokers. Men ages 65 to 75 who have ever smoked should undergo a one-time ultrasound screening test for this condition. Most abdominal aortic aneurysms cause no symptoms, but large ones may cause pain or a throbbing sensation deep in the abdomen. A ruptured one can cause sudden, severe pain in the lower belly or back, nausea, vomiting, sweaty skin, lightheadedness, or fainting.

Thoracic aortic aneurysm. An estimated one in 10,000 people has a thoracic (chest) aortic aneurysm. The greatest risk of this rare condition is a dissection, a tear in the inner wall of the aorta, which can create a blood-filled channel that disrupts blood flow to the body. Symptoms include sudden, severe, sharp pain in the chest, neck, or back. People who have first-degree relatives with a thoracic aneurysm should be screened; so should people with a personal or family history of aortic valve problems or certain genetic conditions, including Marfan syndrome, vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, and Turner syndrome.

Prevention and beyond

To minimize your risk of an aneurysm, keep your blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg (the lower the better, as long you don't feel lightheaded), and don't smoke. A healthy diet and regular exercise are also important. If you are found to have an aneurysm via screening or by chance, it's vital to see a specialist who can monitor your condition. Often, that means periodic imaging tests and, in some cases, a procedure to lower the risk of a rupture.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.