Update on atrial fibrillation

New guidelines focus on lifestyle habits to prevent and control this common heart rhythm disorder.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Atrial fibrillation causes a rapid, chaotic heartbeat that usually comes and goes without warning. Commonly known as afib, it's caused by electrical misfires in the heart's upper chambers (atria). While some people don't notice any symptoms, others feel a fluttering, pounding sensation in their chest and may become lightheaded, dizzy, and breathless during a bout of afib. But the real danger is a heightened risk of serious strokes (see "Atrial fibrillation and stroke").

An estimated one in 11 people ages 65 and older have afib, which becomes more common with age. "There are many things you can do to both lower your risk and prevent the progression of afib," says Dr. Moussa Mansour, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Atrial Fibrillation Program at Massachusetts General Hospital. In fact, lifestyle modifications are now a prominent focus of the latest guidelines for managing afib, he says. Here's a summary of the updated recommendations, published Jan. 2, 2024, in the journal Circulation.

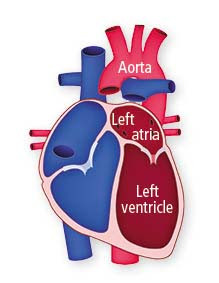

Atrial fibrillation and stroke

During atrial fibrillation, the heart's upper chambers (atria) quiver rapidly instead of contracting forcefully. Blood pools along the walls of the left atrium, eventually forming clots that may break free to travel through the left ventricle (lower chamber) to the aorta (the large vessel carrying blood out of the heart). If the clot lodges in an artery to the brain, it may block blood flow and cause an ischemic stroke. Illustration: © Rujirat Boonyong/Getty Images |

Alcohol and caffeine advice

"The most important advice is about alcohol use, which is one of the first things my patients ask about," says Dr. Mansour. Strong evidence from multiple studies shows that drinking alcohol raises the risk of afib. There's no magic number of drinks considered safe or risky, although the guidelines suggest no more than one per day. But it's clear that the less alcohol you drink, the better, he says.

People also wonder if they should avoid coffee. In some people, caffeine seems to trigger palpitations — the sensation of a skipped, missed, or strong heartbeat. Still, observational studies haven't shown any increased risk of afib among coffee drinkers. In fact, one found that people who drink one to three cups of coffee daily are less likely to have afib than people who drink lower or higher amounts. "Caffeine doesn't seem to be something people need to worry about," says Dr. Mansour.

Weight

Excess weight, on the other hand, is an issue for many people. Obesity, which is defined as a body mass index or BMI of 30 or higher, promotes afib on several fronts. First, it can worsen high blood pressure, and second, it makes people more prone to obstructive sleep apnea. "In addition, clinical studies show that obesity increases fat around the heart," says Dr. Mansour. This promotes inflammation of the heart muscle, which may lead to changes in the structure of the atria, spurring the onset and progression of afib, he adds.

The guidelines recommend that people strive for a BMI of 27 or lower. Research suggests that even modest weight loss (about 10% of your body weight) can help keep your heart rhythm more stable and is linked to better outcomes following treatment for afib.

Exercise

Exercise not only supports weight loss, it can also lower afib burden, which refers to both the duration and frequency of afib. The afib guidelines suggest 210 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous-intensity physical activity per week, which may also help reduce afib symptoms. But Dr. Mansour keeps the advice to his patients simple: "Aim for three to four hours of exercise every week, at a level of effort that's more than a casual walk, but nothing too crazy," he says.

However, dedicated exercise buffs who work out far more than the average person can still develop afib. "If you trained for marathons in your 30s and keep up that level of intensity into your 60s, the recommendation is to do less exercise if you develop afib," says Dr. Mansour. But if exercise is a big deal for you and important for your mental health, there's no hard-and-fast rule about dialing back, he says.

Sleep

Dr. Mansour recommends that anyone with afib who snores should be tested for sleep apnea, a condition marked by brief pauses in breathing that often triggers loud snoring, grunts, and gasps. More than one in five people with afib have sleep apnea, and treating the problem may lessen afib recurrence.

Image: © patrickheagney/Getty Images

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.