What is a bubble study?

Ask the doctor

Q. To my surprise, I recently had a minor stroke. I have fully recovered. My doctor now wants to do a "bubble study." What is this test, and why it is done?

A. A bubble study, which is done during an echocardiogram (heart ultrasound), can provide added information about blood flow through your heart. Doctors often do bubble studies on people who experience an unexpected stroke — that is, those who have no obvious stroke risk factors, such as high blood pressure or atrial fibrillation. The results can provide clues about a possible cause and may affect the treatment you receive.

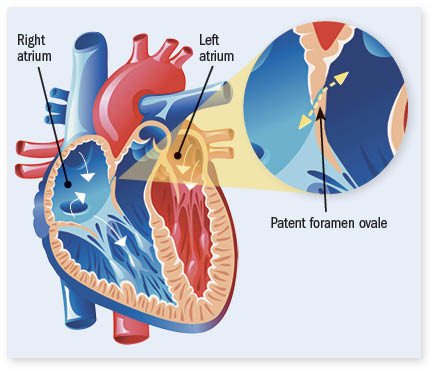

During the test, a technician injects a solution into a vein in your arm. The fluid contains tiny bubbles of air, which then circulate through your bloodstream to the right side of your heart. You'll be asked to cough or bear down, which briefly increases the pressure in the heart's right side. On the ultrasound image, the bubbles can be seen traveling into the heart's upper chamber (atrium), then down to the lower chamber (ventricle), and then out through the pulmonary artery into the lungs, where they are filtered out of the blood.

But in some people, bubbles are seen traveling through a tiny, flaplike tunnel between the right and left atria. This opening is present in all babies as a normal part of development and usually closes up within a few weeks of birth. But in about 25% of people, the hole fails to fully close and is known as a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

For the most part, this condition is harmless, and most people with a PFO don't know they have one. However, some PFOs may be responsible for certain rare strokes, which are thought to happen when a blood clot travels between the right and left atrium. Because the clot bypasses the lungs (which trap tiny clots before blood recirculates through the body), it can travel to the brain, lodge in a blood vessel, and cause a stroke.

To better assess the odds of this happening, you may also receive a transcranial Doppler study in conjunction with the bubble study. This specialized ultrasound of the brain's vessels can show if the bubbles injected into your vein are moving all the way up to the brain. When that's the case, the PFO may be more likely to cause a stroke.

PFOs could be at fault in some so-called cryptogenic strokes (those with no clear cause), especially in people ages 60 and younger. For these people, if testing shows a PFO, doctors sometimes recommend a procedure to close the opening, especially if it is large. But for most people, clot-preventing drugs are the initial treatment.

Image: © rabbitteam/Getty Images

About the Author

Deepak L. Bhatt, M.D., M.P.H, Former Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.