What makes water workouts so worthwhile?

Aquatic exercise is an effective, joint-friendly way to strengthen your cardiovascular system and muscles alike.

- Reviewed by Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Summer's sultry weather often encourages people to spend time in a pool, lake, or ocean. Water can be both refreshing and relaxing — and it's also a great setting for doing a heart-healthy workout, whether that's swimming laps or doing water aerobics.

"Swimming is one of the best forms of cardiovascular exercise," says Dr. Aubrey Grant, a sports cardiology fellow at the Cardiac Performance Laboratory at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital. In fact, water-based exercise offers several unique advantages over aerobic exercise done on land, he notes.

Get into the swim of things

Swimming is a full-body exercise that uses nearly every muscle in your body to propel you forward. And because you're horizontal in the water, blood doesn't pool in your lower body like it does when you're exercising while upright, Dr. Grant explains. That, coupled with the pressure of water on your body (called hydrostatic pressure), increases blood flow from your extremities toward the center of your body and your heart. "This increases the amount of blood your heart pumps per minute, called cardiac output. Your heart becomes more efficient, which means your heart rate is a little lower during swimming compared with other types of exercise," says Dr. Grant.

Moving your body through water provides far more resistance than moving through air, which means swimming strengthens your muscles and cardiovascular system simultaneously.

Water aerobics advantages

Still, swimming requires a certain amount of coordination and skill. If it doesn't come naturally to you, water aerobics can be a good alternative. Doing water aerobics (also called aquafit and aquarobics) also targets the heart and muscles together.

The simplest version is pool walking or jogging, done in water that's at least waist-deep (the deeper the water, the greater the resistance and effort). Added resistance translates to extra calorie burn compared with land-based exercise. For example, a 150-pound person burns about 250 calories jogging for 30 minutes on land. But jogging in water for 30 minutes burns about 350 calories. You can also do other moves like jumping jacks (see illustration) for a do-it-yourself water workout. For more examples, see the Harvard Special Health Report Aqua Fitness (/af).

An instructor-led class, which is often set to music, can be a nice introduction to water aerobics. To increase resistance and maximize strength gains, you can use equipment like foam dumbbells or paddles. Some classes include interval training, which alternates between lower- and higher-intensity exercises. In addition to those intensive workouts, there are more mellow alternatives that mimic other popular forms of land-based exercise, such as water-based Zumba, yoga, tai chi, and Pilates.

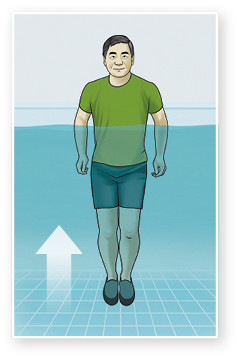

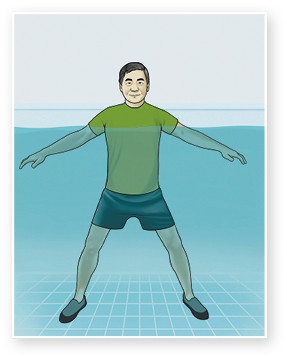

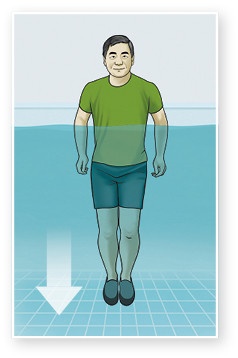

Jumping jacks

1. Stand with your feet together and your arms at your sides. 2. Jump, separating your feet as you raise your arms out to the sides. Keep your hands below the surface. 3. Jump, bringing your feet back together and your arms down to your sides. Repeat as many times as you can in 60 seconds. Exercise illustrations by Alayna Paquette |

Aquatic therapy

Water can be an ideal setting for people with injuries or health conditions that make other forms of exercise painful or challenging. Aquatic therapy (which may be covered by insurance) features one-on-one exercises with a physical therapist or another licensed professional for a limited number of sessions.

"I see patients who tell me they want to exercise and lose weight, but they're unable to walk because of chronic lower back or knee pain," says Audrey Schmidt, a physical therapist at Harvard-affiliated Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. Doing gentle exercises while submerged in water takes stress off your joints, and the water's warm temperature (usually around 90° to 93° F) has a therapeutic effect. The conditions Schmidt treats most often include fibromyalgia, balance problems, and musculoskeletal pain in the lower back, neck, knees, or shoulder. Ideally, aquatic therapy serves as a bridge for people to be able to exercise on their own, says Schmidt, who urges her patients to find a nearby pool so they can maintain and build on their progress.

About the Author

Julie Corliss, Executive Editor, Harvard Heart Letter

About the Reviewer

Christopher P. Cannon, MD, Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.