Ask Dr. Rob about OCD

We've all had times when we focused on a particular thing — something the boss said at work, a song that played in your head all day, or an important upcoming event. And we've all had the experience of feeling compelled to do something just one more time — making sure the oven is off or checking just once more that the front door is locked. While these experiences are common and normal, imagine they were persistent, consuming, and debilitating — that's what Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is like.

What is obsessive-compulsive disorder?

OCD is a condition in which a person experiences recurring and uncontrollable thoughts and behaviors that disrupt normal function, reduces quality of life, or both. The condition gets its name because the recurring thoughts (obsessions) lead to repeated behaviors, called compulsions. It's relatively common, affecting about 1% of the population; about half of cases develop during childhood or teenage years.

The cause of OCD is unknown. However, a number of risk factors have been identified, including:

- a history of OCD in a parent, sibling, or child, especially if the relative developed the disease as a child

- prior history of physical or sexual abuse

- recent Streptococcal infection (though most strep infections do not cause or worsen OCD)

- certain brain abnormalities (as demonstrated by MRI or other imaging tests).

I'm constantly washing my hands and cleaning things. Do I have OCD?

Symptoms and signs: Some people with OCD have both obsessions and compulsions while others may be bothered more by one than the other. Symptoms may improve and worsen over time. Many people with OCD realize their thoughts are not rational but are able to reduce their anxiety about the obsessions only if they perform the repetitive behaviors.

Common obsessions include:

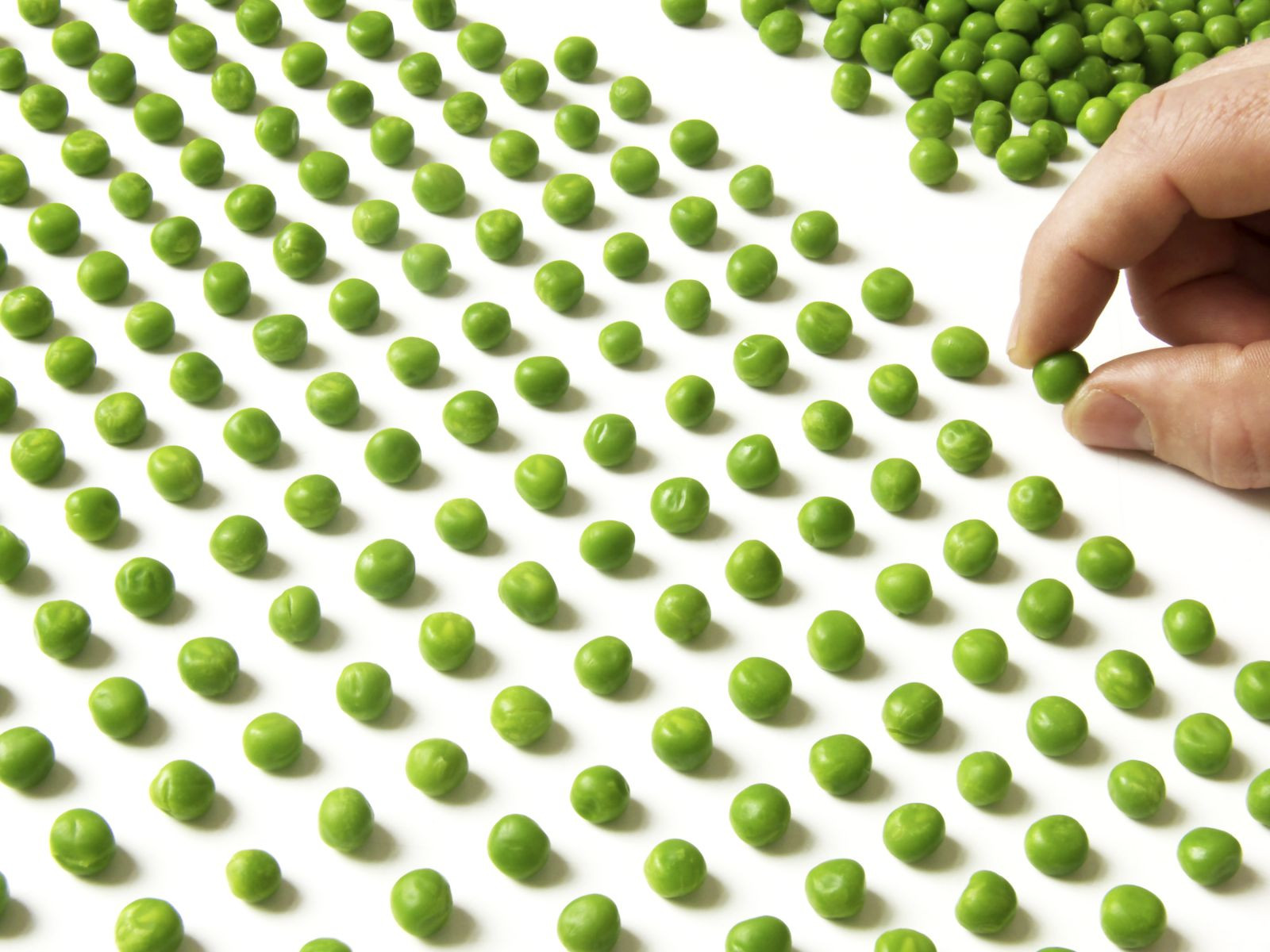

- needing to have things in a particular order

- anxiety about germs or being unclean

- intrusive thoughts about aggression, religion, or sex.

Common compulsions include:

- repeated handwashing or cleaning things

- rearranging objects over and over to get them in perfect order

- rechecking that something's been done properly such as repeatedly packing a repacking a suitcase.

What test is used to diagnosis OCD?

Diagnosis: While some of the thoughts or behaviors experienced by people with OCD occur normally in healthy people, OCD should be considered when these thoughts and behaviors are:

- uncontrollable

- getting in the way of normal functioning

- taking up considerable time (for example, an hour or more each day)

- relentlessly present.

Doctors have specific tests and criteria they rely upon to make the diagnosis.

My teenage son was just diagnosed with OCD. Will he have this condition for the rest of his life?

Expected Duration/Prognosis: While OCD can be lifelong, the prognosis is better in children and young adults. Among these individuals, 40% recover entirely by adulthood. Most people with OCD have a marked improvement in symptoms with therapy while only 1 in 5 resolve without treatment. OCD may cause lifelong social and developmental problems when it begins in childhood. For example, young people with OCD may have difficulty socializing with their peers, establishing friendships and relationships, and may struggle in school. Later, they may be unable to keep a job.

OCD is common in my family. How can I prevent myself from having this condition?

Prevention: There is no known way to prevent the development of OCD. However, avoiding certain stressful situations may prevent triggering of symptoms and treatment may prevent worsening of symptoms.

Is there an effective treatment for OCD?

Treatment: Standard treatment for OCD includes psychotherapy, medication, or both. Most of the time, treatment is effective. Many people with OCD also have an anxiety disorder or depression so treatment choices may be determined in part by the presence or absence of these other conditions.

Certain "self-help" treatments can be beneficial, such as becoming more aware of "triggers" and how to avoid them and using relaxation techniques, yoga, and massage to lessen anxiety associated with OCD.

Psychotherapy often includes forms of cognitive-behavior therapy such as:

- education about OCD and how cognitive behavioral therapy can help.

- exposure and response prevention in which a person is exposed to situations that trigger symptoms while learning that no harm will follow if refraining from the compulsive behavior. For example, a person may be exposed to their opened front door and encouraged to lock it only once. While this may cause distress (due to the inability to recheck and relock the door repeatedly), over time, the lack of harm associated with this may lessen the need to relock the door repeatedly.

- cognitive therapy intended to help people with OCD to reassess their mistaken beliefs about their obsessions. For example, talking about how locking the door once is adequate to protect the house and how refraining from repeated locking is unlikely to result in a break-in.

Medications that may be effective for OCD include:

- fluoxetine

- fluvoxamine

- sertraline

- clomipramine

- venlafaxine

- risperidone.

While medication therapy can be effective, side effects are common and it can take some time to identify the most effective and well-tolerated drug.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an investigational approach for people with severe symptoms of OCD that does not improve enough with medications or psychotherapy. With DBS, electrodes are implanted by a surgeon into specific areas of the brain allowing the application of electrical impulses to stimulate or inhibit those areas. For reasons that are not entirely clear, this approach can be effective for people with OCD.

The Bottom Line

OCD is a common and potentially debilitating condition in which a person experiences recurring and uncontrollable thoughts and repetitive behaviors that interfere with normal functioning. The condition may be caused by abnormal brain function, it can run in families and may be triggered by infections or other environmental factors. Treatment is usually effective and includes psychotherapy, medications, or their combination.

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Clinical Chief of Rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston where he teaches in the Internal Medicine Residency Program. He is also the program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship. He has been a practicing rheumatologist for over 25 years.

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, is associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and Clinical Chief of Rheumatology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston where he teaches in the Internal Medicine Residency Program. He is also the program director of the Rheumatology Fellowship. He has been a practicing rheumatologist for over 25 years.

To learn about the latest and most effective treatment approaches, including cognitive behavioral therapies, psychotherapy, and medications, buy the Harvard Special Health Report Coping with Anxiety and Stress Disorders.

About the Author

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.