All about gout

This old disease is becoming more common, but gout can be easily treated and then prevented — with the right care.

- Reviewed by Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Unless you've experienced it firsthand or know someone who has, gout may seem like a museum piece of a disease — a condition that once afflicted corpulent men of means but doesn't get mentioned much these days. Even the name seems archaic and unscientific. Gout comes from gutta, Latin for drop, a reference to the belief that it was caused by a drop-by-drop accumulation of humors in the joints.

But gout is still very much with us, and the number of Americans affected seems to be increasing, at least partly because of the obesity epidemic. Gout remains a disease that mainly affects middle-aged and older men, although postmenopausal women are vulnerable too, perhaps because they lack the protective effect of estrogen. The diuretics ("water pills") that many people take to control high blood pressure are another contributing factor. Gout can also be a problem for transplant recipients. There are several reasons for this but medications, such as cyclosporine, taken to reduce the chances of organ rejection and reduced kidney function are major contributors.

The encouraging news is that almost all gout cases are treatable. In fact, gout is one of the few treatable and preventable forms of arthritis, an umbrella term for dozens of conditions that cause inflammation in the joints. The challenge is making sure people get the gout care they need and follow through on taking medications.

What causes gout?

Purines are a group of chemicals present in all body tissues and in many foods. Our bodies are continually processing purines, breaking them down and recycling or removing the byproducts. Uric acid is one of the byproducts and, normally, any excess leaves in the urine. But in some people, the system for keeping levels in check falls out of kilter. Usually it's because the kidneys aren't keeping up and excreting enough uric acid, but sometimes it's a matter of too much uric acid being produced or it's a combination of both.

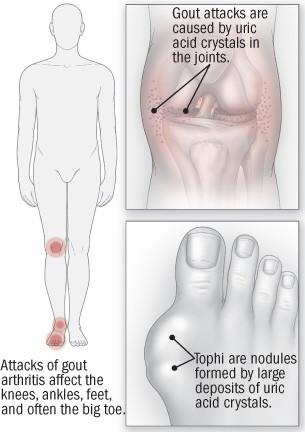

Gout occurs when surplus uric acid coalesces into crystals, which causes inflammation in the joints. Pain, swelling and loss of joint motion are typical. (Technically, the crystals consist of sodium urate, although for simplicity's sake they're often referred to as uric acid crystals.) The crystals appear most often in the joints, but they may also collect elsewhere, including the outer ear, in the skin near the joints, and the kidney.

High concentrations of uric acid levels in the blood — the medical term is hyperuricemia — are necessary for the crystals to form. Yet many people with hyperuricemia never develop gout, and even when they do, they often have had high levels of uric acid in their blood for years without any symptoms. People with hyperuricemia with no symptoms might be coached to make lifestyle changes — losing weight would often top the list — but hyperuricemia by itself is usually not treated.

Gout predisposing factors

Dr. Hyon K. Choi, now at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and epidemiologists at Harvard have used data from the Harvard-based, all-male Health Professionals Follow-up Study to make a series of comparisons between the 730 men in this study who developed gout during a 12-year period and the vast majority of those in the study who did not. The result is an impressive dossier on the risk factors for gout, at least as they pertain to men.

Dr. Choi's findings on weight weren't surprising and fit the stereotype: gout is, in fact, a heavy man's disease. Eating lots of meat and seafood and drinking lots of alcohol spells gouty trouble. And the Homer Simpsons of the world are gout candidates: two-or-more-a-day beer drinkers are more than twice as likely to get gout as nonbeer drinkers, which makes sense, because beer contains a lot of purines.

Soft drink fanciers might be in the same gouty boat. High fructose intake was linked to gout in a Choi-led study published in 2008. Uric acid is one of the products of fructose metabolism, and there's good evidence from controlled feeding studies that fructose increases uric acid levels in the blood. Much of the fructose in today's American diet comes from the high-fructose corn syrup (which is about half fructose and half glucose) that's used to sweeten soft drinks and many other foods and drinks.

High blood pressure is another major risk factor for gout. It gets complicated, though, because the diuretics taken to lower high blood pressure increase uric acid levels, so the treatment as well as the disease is associated with gout.

Finally, gout does run in some families and we know that certain genes increase the risk of gout.

Gout symptoms and complications

Gout is not gout until symptoms occur. When they do, they usually come on suddenly and, at least initially, affect a single joint. Within hours, that joint becomes red, swollen, hot, and painful — they're called gout attacks for a reason. It's easy to mistake a gout attack for a localized infection of a joint. The metatarsophalangeal joint at the base of the big toe (where the toe meets the foot) is often the site of the first attack, but the knees, ankles, and joints between the many small bones that form the foot are also common sites. People who already have osteoarthritis — the most common form of arthritis — often experience their gout attacks in the joints of the finger.

Treating a gout attack

As is true for many painful conditions, the first-line treatment for a gout attack is taking one of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as diclofenac, ibuprofen, or indomethacin. For people who can't take NSAIDs, a drug called colchicine is an alternative. It's been used for centuries — maybe even longer — specifically for gout. The trouble with colchicine is its side effects, especially the copious diarrhea. If neither an NSAID nor colchicine is an option, then gout attacks can be treated with an oral corticosteroid, such as prednisone, or with corticosteroid injections into the joints. Newer options, reserved for people who haven't had success with other treatments, include injections of anti-inflammatory drugs called IL-1 inhibitors. These include anakinra (Kineret) and canakinumab (Ilaris).

Preventing gout attacks

For years, gout patients were told they had to follow a purine-restricted diet to stave off attacks, but those diets weren't very effective and people had a difficult time sticking to them. Now the easier-said-than-done advice is to lose weight, and also to cut back on alcohol, especially beer. Big meat and seafood eaters may be told to curb their appetites and instead eat more low-fat dairy foods. Diuretics tend to increase uric acid levels. If someone with gout is taking one, a doctor might explore lowering the dose or switching to a different medication.

But the most important fork in the road for gout sufferers is whether to start taking a drug that will lower their uric acid levels. Once people start taking these drugs, they usually must take them for the rest of their lives. Going on and off a uric acid–lowering medication can provoke gout attacks. Experts have differing opinions, but many agree that the criteria for starting therapy include frequent (say, two or three times a year) attacks, severe attacks that are difficult to control, gout with a history of kidney stones, or attacks that affect several joints at a time. Guidelines also recommend uric acid-lowering treatment if gout has caused joint damage, or if a person with gout also has kidney disease.

When starting a uric acid-lowering drug, flares of gout are common because any change in uric acid (up or down) can trigger an attack. For this reason, an anti-inflammatory drug such as colchicine is recommended for at least the first few months of uric acid-lowering treatment.

Allopurinol is the first-line uric acid–lowering drug. It needs to be taken only once a day and reduces uric acid levels regardless of whether the root problem is overproduction of uric acid or inadequate clearance by the kidneys. Sometimes people develop a mild rash when they start allopurinol, although rarely there's a dangerous allergic reaction. Old guidelines warned against prescribing allopurinol for people with kidney disease, but with proper dosing, the drug is usually well tolerated and effective even for people with kidney disease. Underdosing has long been a problem. The standard starting dose is 100 mg per day (or less if a person has kidney disease); many doctors do not increase it above 300 milligrams (mg), but that might not be enough to reach the commonly accepted target level for uric acid of 6 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or less. Most people can take doses of 400 mg or more (if needed) without any problems, although higher doses do mean taking extra pills.

A newer drug, febuxostat (Uloric), is similar to allopurinol in the way it works. In head-to-head trials, febuxostat looked to be more effective than allopurinol at controlling uric acid levels, although that was likely because the allopurinol dose in the study was too low.

Probenecid is a third choice. Like allopurinol, it's been on the market for decades, so it has a long track record. Probenecid works by increasing uric acid excretion by the kidneys so it can trigger the development of kidney stones and is not a good option for people with kidney problems. Another drawback to probenecid is that it has to be taken twice a day.

Pegloticase (Krystexxa) is another option. It lowers the productrion of uric acid and is generally reserved for people who have severe gout and have not had success with other treatments or cannot tolerate them. This medication is given intravenously every two weeks along with weekly oral methotrexate to prevent side effects and increase effectiveness. Daily folic acid, a B vitamin, is also recommended to reduce the risk of methotrexate-related side effects.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the uric acid–lowering therapy is sticking with it. A number of studies have demonstrated that up to 80% of people prescribed allopurinol were taking it incorrectly or not at all. Poor adherence is understandable. Once people are taking an effective gout prevention medicine, there are usually no immediate symptoms to remind them to take the pills daily. And the memory of the last attack is bound to fade, no matter how excruciating it might have been.

Many types of arthritis cannot be prevented and lack medical treatments that reliably work. Gout is different - the treatment is usually straightforward and highly effective. So, if you have gout, ask your doctor about treatment options. Although gout is on the rise, there are now good treatment options for this ancient disease.

The Health Letter thanks Dr. Robert Shmerling for his help with this article. Dr. Shmerling is a Senior Feculty Editor for Harvard Health Publishing and is a member of its Editorial Advisory Board.

About the Reviewer

Robert H. Shmerling, MD, Senior Faculty Editor, Harvard Health Publishing; Editorial Advisory Board Member, Harvard Health Publishing

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.