Ankle-brachial index

Comparing blood pressure at the arm and ankle can reveal peripheral artery disease.

Arteries that deliver blood to parts of the body below the heart don't get nearly as much attention as the coronary arteries that supply the heart or the carotid arteries that supply the brain. They should. These so-called peripheral arteries are anything but peripheral. They're central to good health for the kidneys, intestines, and legs. They are also prone to the same damaging processes that stiffen and clog coronary arteries. Peripheral artery disease causes suffering, disability, and sometimes death among the millions of Americans who have it.

A key test for problems in the peripheral arteries is a blood pressure measurement known as the ankle-brachial index.

Why it is done

In a perfectly healthy circulatory system, blood pressure measured at the brachial artery in the crook of the arm (which is near the heart) is a good gauge of blood pressure elsewhere in the body. But when blood must travel through stiff or cholesterol-clogged arteries, the pressure at sites further from the heart can differ from that in the arm. The ankle-brachial index, sometimes called the arm-ankle index, compares blood pressure from two locations. A large difference between the two can signal the presence of peripheral artery disease. The test can also track the progression of the disease or the effect of treatment.

Who needs it?

Anyone with symptoms of peripheral artery disease should have an ankle-brachial index test. The most common sign of this condition is pain or cramping in the calves, thighs, hips, or buttocks when walking, climbing stairs, or exercising that fades with rest. Doctors call this claudication. Wounds on the toes, feet, or legs that don't heal or take a long time to heal are another sign. So is a leg that feels cooler to the touch than other parts of the body, or that looks to be a different shade.

Peripheral artery disease, like coronary artery disease, often doesn't cause symptoms until it is advanced. So an ankle-brachial index is also recommended for people at high risk of developing the disease. This includes smokers or former smokers over age 50; adults with diabetes, high blood pressure, or high cholesterol; those who have had a stroke or mini-stroke; and anyone with a strong family history of heart disease.

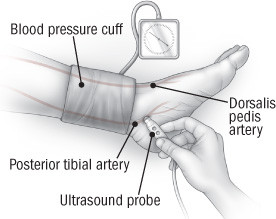

Checking blood pressure at the ankle

To test for peripheral artery disease, blood pressure is measured in two arteries that supply the foot using a blood-pressure cuff and an ultrasound probe. |

What's the procedure?

Having an ankle-brachial test takes 10 to 15 minutes. It can be done in a doctor's office and doesn't require any preparation other than removing your shoes and socks.

You lie quietly on an examination table for a few minutes. A doctor or nurse measures the pressure in both of your arms using a standard blood pressure cuff. He or she then measures the pressure in the posterior tibial artery and the dorsalis pedis artery near each ankle using a pressure cuff and a stethoscope or an ultrasound probe.

The highest pressure recorded at the ankle is divided by the highest pressure recorded at the brachial artery. This gives the ankle-brachial index.

Sometimes the measurements are made before and after exercising.

What it shows

The normal range for the ankle-brachial index is between 0.90 and 1.30. An index under 0.90 means that blood is having a hard time getting to the legs and feet: 0.41 to 0.90 indicates mild to moderate peripheral artery disease; 0.40 and lower indicates severe disease. The lower the index, the higher the chances of leg pain while exercising or limb-threatening low blood flow.

An ankle-brachial index over 1.30 is usually a sign of stiff, calcium-encrusted arteries. These often occur in people with diabetes or chronic kidney disease. In such cases, blood pressure should be measured at the toe, where arteries are less likely to be rigid.

The ankle-brachial index also offers information about general cardiovascular health. An analysis of studies including nearly 50,000 men and women show that a low index (under 0.90) doubled the chances of having a heart attack or stroke or dying of heart disease over a 10-year period.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.