Eight for 2008: Eight things you should know about osteoporosis and fracture risk

Bone health is every woman's concern. Resolve to make it a priority.

How strong are your bones? You may have no idea — until a bone breaks when you push on a stuck window or bend down to pick up something you've dropped. Fractures resulting from such seemingly innocuous activities — sometimes called fragility fractures — are usually the first symptom of osteoporosis, the skeletal disorder that makes bones vulnerable to breakage even without a serious fall or other trauma.

Osteoporosis is responsible for more than 1.5 million fractures each year in the United States, almost half of them vertebral (spine) fractures and the rest mostly broken hips and wrists. Hip fractures usually require hospitalization and surgery and often result in permanent disability or the need for nursing home care. Nearly 25% of hip-fracture patients die within a year. Vertebral fractures not only are painful but also cause a stooped posture that can lead to respiratory and gastrointestinal problems. Having any kind of low-impact fracture boosts the risk of having another.

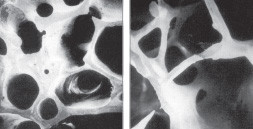

Normal and osteoporotic bone

These are microscopic views of bone. On the left, a 75-year-old woman with healthy bone structure; on the right, a 47-year-old woman with osteoporosis. As you can see, osteoporosis undermines bone strength and resilience not only by decreasing bone mass (total tissue) but also by disrupting the bone's "microarchitecture," or structural organization. |

Mostly a woman's disease

Of the estimated 10 million Americans who have osteoporosis, 80% are women. Another 22 million women are at increased risk for the disease. In both sexes, certain medications (glucocorticoids, aromatase inhibitors, immunosuppressive drugs, chemotherapy drugs, and anticonvulsants) can lead to significant bone loss. So can certain medical conditions. Celiac disease and Crohn's disease, for example, reduce the absorption of calcium and other nutrients needed for bone maintenance. Rheumatoid arthritis, hyperthyroidism, chronic kidney or liver disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, and anorexia nervosa are also associated with osteoporosis.

Currently, a woman's odds of having an osteoporotic fracture are one in three. We can't control all the factors involved, but we need to do all we can to strengthen and preserve our bones. To that end, here are eight important points to keep in mind.

1. Vital nutrients

A healthy diet preserves bone strength by providing key nutrients such as potassium, magnesium, phosphorus, and — of course — calcium and vitamin D. If you don't get enough calcium, your body will take it from your bones. If your diet doesn't supply enough calcium (1,000 to 1,200 milligrams per day), take a supplement. The same goes for vitamin D, which is needed to extract calcium from your food. Food sources of vitamin D are limited, and you may not get enough sun to manufacture adequate amounts through the skin. Experts recommend 800 to 1,000 IU of vitamin D per day (women being treated for vitamin D deficiency take much higher amounts). According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation, vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is the form that best supports bone health. To learn more about other nutrients that affect bone health, visit www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Bone/Bone_Health/Nutrition/other_nutrients.asp.

2. The exercise prescription

Two types of exercise — weight-bearing and resistance — are particularly important for countering osteoporosis. Weight-bearing activities are those in which your feet and legs bear your full weight. This puts stress on the bones of your lower body and spine, stimulating bone cell activity. Weight-bearing exercise includes running, jogging, brisk walking, jumping, playing tennis, and stair climbing. Resistance exercise — using free weights, rubber stretch bands, or the weight of your own body (as in sit-ups and push-ups) — applies stress to bones by way of the muscles. It's especially helpful for strengthening bones of the upper body that don't bear much weight during everyday activities. Merely occasional exercise won't help, though. Aim for at least 30 minutes of bone-strengthening exercise most days of the week. If you have osteoporosis or another pre-existing health condition, consult a clinician about whether you should avoid certain activities, positions, or movements.

Bone turnover basics

Bone continually undergoes a process called remodeling, or bone turnover, which has two distinct stages: resorption (breakdown) and formation. Bone is a storage depot for calcium. When the body needs calcium, bone cells called osteoclasts attach to the bone surface and break it down, leaving small cavities (A). Bone-forming cells called osteoblasts move into these cavities (B), releasing collagen and other proteins to stimulate bone mineralization and replace what was lost. The osteoblasts that become incorporated in the new bone (matrix) are called osteocytes (C). |

Early in life, bone formation outpaces resorption. By age 20, most of us have the greatest amount of bone tissue we'll ever have (peak bone mass). Bone mass declines very slowly until late perimenopause, when bone loss becomes more rapid, due in part to decreased estrogen, a crucial player in bone turnover. Also, after age 50 to 60 our bodies are less able to absorb calcium and produce vitamin D. We continue to lose bone, though more slowly, for the rest of our lives.

3. No smoking, please

Here's yet one more reason not to smoke: Women who smoke lose bone faster, reach menopause two years earlier, and have higher postmenopausal fracture rates. The mechanism isn't known; smoking may lower estrogen levels, or it may interfere with the absorption of calcium and other important nutrients.

4. Know your risk

To screen for osteoporosis, clinicians measure bone mineral density (BMD) — the amount of calcium and other minerals in bone. The best way to assess fracture risk is to calculate BMD at the spine and hip with low-dose x-rays (dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, or DXA) and factor in a woman's age. The World Health Organization's definition of osteoporosis is based on a DXA value called a T-score, which compares the amount of bone a woman has to normal peak bone mass. A T-score of −2.5 or worse indicates osteoporosis. Women who have T-scores of −1.0 to −2.5 have osteopenia and are at increased risk for developing osteoporosis.

Most official guidelines recommend DXA screening for all women starting at age 65, and earlier for women who take medications or have health conditions that increase osteoporosis risk. But reduced BMD is only one risk factor for osteoporosis. You're also at greater risk if you smoke or are older, Caucasian, or thin, or if you had a fracture after age 50 or have a parent who had a hip fracture. The World Health Organization has developed a formula that predicts 10-year fracture risk based on BMD and other risk factors. A calculator based on this formula is available at courses.washington.edu/bonephys/FxRiskCalculator.html.

Clinicians are also interested in bone quality — a complex characteristic that includes bone mineralization, microarchitecture, and the rate of bone turnover. So far, we have no way to noninvasively assess bone quality, but new imaging technologies are being developed that may allow clinicians to visualize the internal structure of bone and gain information that was once available only through biopsy.

5. Bone-preserving drugs

Postmenopausal woman who've had a fragility fracture or received a BMD T-score of −2.5 or worse should take an osteoporosis drug. Women with T-scores from −2.0 to −2.5 should consider drug therapy if they have a parent with a history of hip fracture or one or more other risk factors for osteoporosis.

Most approved osteoporosis drugs (see sidebar) are antiresorptive, that is, they slow resorption, the breakdown phase of bone turnover. Only one drug, parathyroid hormone (Forteo), is anabolic, meaning that it stimulates new bone formation. All medications have side effects, and dosing schedules vary from one to the other, so it's important to explore all the options with your clinician. One adverse effect of bisphosphonates — death of jawbone tissue, usually after dental extractions or oral surgery — has occurred extremely rarely in women taking bisphosphonates for osteoporosis. It mostly has affected cancer patients, who take far higher bisphosphonate doses, usually intravenously.

Several osteoporosis drugs are under investigation, including the mineral strontium in the form of strontium ranelate, and denosumab, a monoclonal antibody that works by blocking osteoclasts, the cells that resorb bone.

Drugs approved for osteoporosisAntiresorptive drugs (slow bone breakdown) Bisphosphonates (prevention and treatment)

Bisphosphonates (treatment only)

Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (prevention and treatment)

Hormone therapy (prevention only)*

Other (treatment only)

Anabolic drugs (stimulate new bone formation) Parathyroid hormone (treatment only)

*Only for prevention in postmenopausal women at significant risk for osteoporosis after non-estrogen drugs have been considered. No longer a first-line therapy. **In a two-year study reported in Maturitas (Aug. 20, 2007), use of an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring produced a small but significant improvement in bone mineral density of the hip and lumbar spine. |

6. Depression connection

Since the mid-1990s, researchers have investigated links between depression and bone loss. In 1996, a New England Journal of Medicine study found that women with a history of major depression had lower bone density at the hip and spine and higher levels of cortisol, a stress hormone associated with bone loss. Since then, many studies have found a similar relationship. Research has also linked selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants with fractures, but cause and effect has not been established. It may be a long time before these connections are fully elucidated. In the meantime, women being treated for depression may want to talk to their clinicians about a BMD test.

7. Weight and weight loss

Weighing less than 127 pounds or having a body mass index under 21 is a risk factor for osteoporosis. Regardless of your body mass index, if you lose weight during the menopausal transition (late perimenopause and the first few years after menopause), you're more likely to lose bone. Avoid ultra-low-calorie diets and diets that eliminate whole food groups. Be aware that bone loss accelerates during the menopausal transition, so if you're trying to lose weight at that time, you may need to boost your calcium and vitamin D intake and bone-strengthening workouts.

8. Avoiding falls

Falling is one of the leading causes of fractures, especially among older women and those with low BMDs. Clear floors of anything that could trip you, including loose cords, stools, pillows, throw rugs, and magazines. Make sure stairways, halls, and entrances are well lit; install night-lights to help you see your way to the bathroom. Add grab bars to your tub or shower; make sure stairways have sturdy handrails. Don't walk around in socks. Limit your alcohol intake. Have your vision and hearing checked regularly. If you take tranquilizers, sleeping pills, or any other medications that could impair your balance, talk to your clinician about reducing or eliminating them.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.