Knees in need

Arthritis sufferers look for answers after a large study finds that glucosamine and chondroitin are ineffective for many.

If your knees ache and creak, you've got lots of company. At least a quarter of everyone over age 55 has had a significant problem with knee pain in the past year. Bad cases can be disabling. Usually the cause is osteoarthritis, a breakdown of the joint cartilage that also causes damage to the bone beneath. There's no cure, which leaves ample room for hope, hype, and halfway measures — and some strange experimentation. Several years ago, German researchers reported that applying leeches to an osteoarthritic knee relieved symptoms. Apparently, leech saliva has some painkilling properties.

Something tells us that leech therapy isn't going to catch on, even if it were to make old knees feel spry again. But glucosamine, which is made from shellfish, and chondroitin, which is made from cow cartilage, already have. Every day millions of Americans — including, reportedly, President Bush — take the supplements, which supposedly work by rebuilding cartilage. Most doctors have had a tolerant attitude about this. Conventional medicine doesn't have any sure thing. Knee replacements are major surgery and a last resort. As long as the supplements don't do any harm, why not give them a try?

No better than placebo

But doing no harm doesn't mean doing any good, either. There have been scores of studies of glucosamine and chondroitin, but many of them have been small, sponsored by groups with a vested interest, or both. It's the same murky situation with many supplements, so the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is running several of the popular ones through the gantlet of large clinical trials. The NIH-funded Glucosamine/chondroitin Arthritis Intervention Trial, or GAIT, included 1,583 people with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. The researchers randomized them to take the supplements in various combinations or placebo pills, and then asked the volunteers to grade their knee pain six months later. The results, which were published in February 2006, showed no difference between the placebo pills and glucosamine and chondroitin.

Some experts say the door is still ajar because a subgroup analysis showed some benefit from the supplements among people with more severe cases of osteoarthritis. But subgroup analyses are inherently suspect because the number of subjects involved gets small, and positive findings may occur just as a matter of chance. There's also some question about the glucosamine compound tested in the trial and whether it has the same effect as the glucosamine sulfate now being sold.

Also, as with the results of every study, what's true on average may not apply to everybody. There are individuals who swear by the relief they get from glucosamine and chondroitin. While that could be just a placebo effect, it may be true for some.

Bowlegged and knock-kneed

The basic design is pretty straightforward: Your knee is a one-way hinge formed by the large thigh bone, or femur, and the shinbone, or tibia. It isn't a terribly tight fit between the knobby ends of the femur and the flat top of the tibia. But having some give is an advantage; it allows the knee to twist a little bit. Cartilage and fluids keep it lubricated. If our knees seem flawed and liable to give out, it's because we ask an awful lot of them. Even normal movements put loads equal to two or three times our body weight on the knees — and body weights are ballooning.

Because of the wide pelvis and the angle of the femur, the natural alignment is to be a little knock-kneed (valgus). But we have a tendency to fall out of alignment, so we end up bowlegged (varus) or more knock-kneed than we should be.

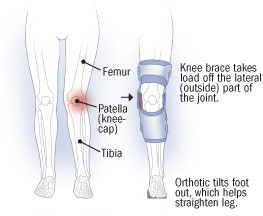

Bowleggedness, which is the more common problem in people with osteoarthritis, puts pressure on the inside (medial side) of the knee, where the femur and tibia meet, and opens up the space between those two bones on the outside (lateral side) of the knee. If you're knock-kneed, it's just the opposite: There is pressure and stress on the outside of the knee and wider space between the femur and tibia on the inside. These malalignments can cause a vicious cycle, explains Dr. David T. Felson, an osteoarthritis expert at Boston University: "You may start out with just a little bit of malalignment but have an otherwise normal knee. If you're varus [bowlegged], that malalignment may cause a little divot in the cartilage on the inside of the knee, but the outside space opens up. You get more malaligned, which causes more load on the inside of the knee and more damage to the cartilage."

The kneecap, or patella, gets involved when you bend your knee. That motion slides the patella over a groove between the knobby ends of the femur. If you're putting weight on your knees as you bend — as you do when you climb stairs — there's a tremendous amount of pressure on the patella as it moves back and forth over the end of the femur. So if it falls out of alignment, or if the cartilage on its back side is damaged, it can be painful. Much of the pain from knee osteoarthritis comes from the patella — or, in medical terms, the patellofemoral joint.

Women are prone to patellofemoral osteoarthritis because their pelvises are wider, so the femur comes into the knee joint at a sharper angle. That angle has the effect of tugging the patella to the outside.

|

Valgus (knock-kneed)

Varus (bowlegged)

|

What can you do?

Wearing a good pair of running shoes is a good place to start even if you aren't a runner. Doug Gross, a physical therapist and a researcher at Boston University with Dr. Felson, recommends buying them at a store that caters to runners. The salespeople are more likely to understand knee and foot problems and how the right shoe might help you. Running shoes are made to accommodate either pronation (rolling on the inside of the foot) or supination (rolling on the outside).

You can buy those knee supports made of stretchy material that fit over the knee like a sleeve. Most drugstores sell them. They may help give you some added stability because the pressure on the skin provides a sensory cue for your muscles to contract when needed, even though sleeves do little to change biomechanics or alignment.

You can also buy over-the-counter (OTC) orthotics that fit into your shoe. They can help if you have a mild case of osteoarthritis. But the drugstore brands pose problems. Most are made so that they're thicker on the inside edge, which may be more suitable for knock-kneed malalignment and not helpful if you're bowlegged. Orthotics can also make foot and ankle problems worse. In short, they may be worth a try, but you have to be sure that they aren't aggravating your problems.

You can buy OTC knee braces, but it's better to get one through a doctor after your knee problems have been properly diagnosed and analyzed. A good knee brace needs to be custom-made, so they are expensive, although if you have health insurance, it should be covered. Design has improved, but they're still bulky, and may not fit under a pant leg. In fact, for doctors and physical therapists, getting patients to wear the knee brace is one of the biggest challenges. On the other hand, if the osteoarthritis is really bad, people are more than willing.

For patients, the hardest part may be finding a doctor who understands malalignment and how it can best be corrected. Orthopedists are surgeons. Rheumatologists, many of whom see osteoarthritis patients, are usually focused on the inflammatory and other medical aspects of the condition, not biomechanics and knee braces. Try to find a doctor, regardless of his or her specialty, who can help you with bracing or exercising, or give you a referral to a physiatrist (a doctor who specializes in rehabilitation) or a physical therapist who will.

Exercise: Pain is not gain

Exercise is crucial, but it can make knee osteoarthritis worse if you're not careful. Pain and swelling can have an inhibitory effect on muscles, reducing their strength. Exercise that is too stressful can make this worse, resulting in further weakening of the very muscles that you want to strengthen. Following the "no pain, no gain" motto is counterproductive. To be effective, strengthening exercises should be gradual and not provoke greater knee pain. Getting a knee brace, orthotics, or both to correct malalignment before you start an exercise program may make a difference.

Exercises shouldn't put too much weight on the knee. For that reason, pool workouts are ideal. Strengthening the quadriceps, the four muscles that form the front of the thigh, is often a goal, but Gross isn't a fan of the straight-leg lifts that people do to achieve that. He'd rather have people do exercises that are more closely related to their everyday activities: "If you do a lot of straight-leg lifts you'll be good at doing them, but is that what you really want?" Biking can help and has the added benefit of giving you a cardiovascular workout. But depending on how hard you cycle, it can load the patellofemoral joint. Ideally, like the knee brace, your exercise program should be custom-made under a doctor's supervision.

|

Alternative approaches

|

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.