Pancreatic cancer: An update on a 'stealth' cancer

Treatment advances have been slow in coming. What makes this cancer so intractable?

There's been a steady stream of good news about cancer lately, from targeted therapies like Gleevec to new strategies like anti-angiogenesis, which zeroes in on the proliferating blood vessels that feed tumors. Some cancers — for example, Hodgkin's disease, a type of lymph cancer — are increasingly treatable. The number of Americans dying from breast and colon cancer is decreasing.

But good news about pancreatic cancer is harder to come by. Doctors haven't yet discovered how to detect it early. Treatment has progressed some, but there's been nothing close to a breakthrough.

Now there's a move to go back to medicine's drawing board: basic research. The hope is that a better understanding of the disease's genetics and molecular-level mechanisms will reveal an Achilles' heel and a target for more effective treatment. Early detection is another goal because pancreatic cancer is rarely detected until it has spread (metastasized).

Meanwhile, like other diseases, pancreatic cancer now has advocacy and support groups that help patients and their families, raise money, and push for more research.

|

The pancreas: A hidden organ

|

Symptoms can be vague

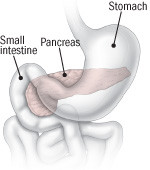

The pancreas has two functions — releasing fluids and enzymes into the small intestine to aid digestion, and producing hormones (mainly insulin and glucagon) that are instrumental to the body's use of sugar.

Only about 10% of pancreatic cancers occur in the hormone-producing, or endocrine, tissues known as the islets of Langerhans.

Far more common are cancers that originate in the tissues that produce and deliver enzymes and digestive fluids. These exocrine cancers, as they're called, can develop in any part of the pancreas, although most (60%) start in the head of the organ, which nestles up against the curved upper portion of the small intestine.

Occasionally the disease does produce symptoms that serve as an early warning. A tumor in the head of the pancreas can pinch off the bile duct, so bilirubin from the liver and gallbladder back up into the bloodstream. The resulting yellow discoloration of the skin and eyes — jaundice — accounts for the majority of diagnoses that occur soon enough for surgery.

But many times, in its early stages, pancreatic cancer doesn't cause any symptoms. Those that do occur — abdominal discomfort, weight loss, not being hungry — can be mistaken for indigestion or some other minor gastrointestinal problem.

Not many risk factors

Smoking is one well-established risk factor. Smokers are two to three times more likely to get pancreatic cancer than nonsmokers are. Some studies have implicated high-fat diets.

Pancreatic cancer is clearly linked to some forms of chronic pancreatitis, which has various causes, including alcohol abuse. But whether there's a connection between alcoholism and pancreatic cancer is far from clear. If there is one, it doesn't seem to be very strong.

Isolated cases of acute pancreatitis, such as those caused by gallstones, don't appear to increase risk for the disease.

Incidence is holding steady

Eleventh among cancers in the number of new cases diagnosed each year (the incidence), pancreatic cancer isn't the most common type of cancer. It is, though, one of the deadliest, ranking fourth among cancers in the number of deaths it causes. The median survival time is about six months. Fewer than one in every five Americans diagnosed with the disease will be living a year later.

One bright spot is that its incidence has been level despite demographic trends that would tend to pull it up.

Like many cancers, pancreatic cancer is an older person's disease: 80% of those diagnosed with it are older than 60. Because of increased longevity and the aging of the baby boom generation, the number of older Americans is growing rapidly.

Yet over the past several decades, its incidence has been steady: 11 to 12 new cases diagnosed each year per 100,000 Americans. (In absolute numbers, that meant 33,730 new cases in 2006, according to the American Cancer Society estimate.) The declining number of smokers may be offsetting the aging population.

Breakthroughs wanted

Pancreatic cancer can be treated surgically by removing the tumor if the cancer hasn't spread to blood vessels, distant lymph nodes, other organs — a big if, given that it's so often diagnosed late. Fewer than 20% of pancreatic tumors can be removed surgically.

A major change in treatment occurred with the introduction of the chemotherapy drug gemcitabine (Gemzar) for postsurgical use. Gemcitabine (pronounced jem-SITE-a-bean) is in a class of medications known as antimetabolites that work by interfering with cancer cell growth. It's used after surgery to keep the cancer from coming back.

Findings reported by a German group in January 2007 in the Journal of the American Medical Association bolstered arguments that using gemcitabine might be preferable to the standard postsurgical treatment in this country, which involves using radiation and an older drug, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Using gemcitabine after radiation and 5-FU may benefit some patients. But experts have been debating the nuances of postsurgical treatment for years and will continue to do so. Sadly, the bottom line is that no matter how treatments are mixed and matched, about 75% of patients who have surgery will die of recurrent disease within three to four years.

Combining drugs, often in a one-two punch, has worked with some cancers. Researchers have tried that approach with pancreatic cancer. Over a dozen studies have teamed gemcitabine up with other drugs, including some of the brand-new agents like bevacizumab (Avastin), an anti-angiogenesis drug, and erlotinib (Tarceva). The results have been disappointing.

One reason that pancreatic cancer may be so hard to treat is that the pancreas is not encased in a membrane as other organs are. This "nakedness" may make local spread more likely. In addition, pancreatic tumors also get cocooned in scarlike tissue that creates a low-oxygen environment, which makes radiation and chemotherapy less effective. Lastly, the genes of pancreatic cancer cells have multiple mutations, which may be why they can fend off chemotherapy drugs so well.

Gain against pain

When pancreatic cancer can't be treated surgically, doctors do their best to ameliorate symptoms and help people live a little longer.

If, for example, the pancreatic tumor is obstructing the bile duct or gastric outlet, doctors can open the blockage with a stent or surgical bypass.

Pain can be managed in a number of ways. Opioids (such as fentanyl, morphine, and oxycodone) are highly effective. Doctors are having success with injections of alcohol into (or around) nerves near the pancreas.

Chemotherapy and radiation may also be part of palliative care, as it is called, reducing pain and other symptoms by shrinking the size of the tumor. Gemcitabine is beneficial in this regard.

Back to basics

Genetic studies. Pancreatic cancer does run in some families. One example is former President Jimmy Carter's family: His father and a brother and sister died of pancreatic cancer.

Researchers have also found that pancreatic cancer is more common in families with several rare inherited cancer syndromes (Peutz-Jeghers to name one) that until recently weren't associated with the disease. Researchers have recently made the intriguing discovery that mutations in the BRCA2 gene, first identified as a breast and ovarian cancer gene, may also be a causative factor in pancreatic cancer. Gloria Petersen, a Mayo Clinic researcher, is creating a large national pancreatic cancer registry in hopes of identifying more genes associated with the disease.

In December 2006, the field of pancreatic cancer genetics got its most exciting news in years: Research published in the online journal PLoS Medicine identified the first gene specifically implicated as a cause of pancreatic cancer — a mutated palladin gene.

The palladin gene produces a protein that makes up the cell walls (the name is a reference to the Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio). The protein generated by the mutated version may permit those cells to move faster than normal cells, which could explain why pancreatic cancer spreads so rapidly to other parts of the body.

Other genetic abnormalities that accompany pancreatic cancer include mutations of the K-ras gene (found in 90% of pancreatic cancers) and the p53 tumor cell suppressor gene (found in 50%–70%).

Early detection. An especially exciting area of research involves the search for substances that could aid in spotting pancreatic cancer earlier. The mutated palladin gene — or the protein it expresses — might serve as such a biomarker.

There's considerable interest in certain growth-regulating proteins — known collectively as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) — that appear to play a role in the underlying mechanism of pancreatic cancer and might be used for early diagnosis.

So far none of the imaging technologies — CT scans, MRIs, ultrasound — have been shown to work for screening. But there are ongoing studies in high-risk individuals, which may show that a combination of tests will be useful in finding abnormal growths early.

Pancreatic cancer doesn't seem to start off with a bang. "It doesn't grow that fast," says Dr. Robert Mayer, a Harvard pancreatic cancer expert. "It's just hard to identify." Researchers think there may be an extended precancerous stage when lesions known as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias are localized. It's possible these lesions release a protein into the blood that will be useful in screening and early detection.

Animal models. Pancreatic cancer research has long been hampered by a lack of an animal model that mimics the human disease. Animal models allow researchers to look for new biomarkers and try untested therapies without putting humans at risk. Using a technique of cross-breeding to create genetic abnormalities similar to those in human patients, investigators at several centers, including the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, have developed a very promising mouse model. Researchers at Johns Hopkins are working on a zebrafish model.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.