The shingles vaccine: Why hasn't it caught on?

ARCHIVED CONTENT: As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date each article was posted or last reviewed. No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.

The cost and other factors are to blame.

When the FDA approved Zostavax in the spring of 2006, it seemed like the shingles vaccine was going to make a big splash. The large clinical trial that the agency based its approval on showed that the vaccine halved the risk of getting shingles. Even more impressive, it cut by two-thirds the risk of developing postherpetic neuralgia, the aftermath of shingles that develops in about one in every three cases in people age 60 and over. Shingles can be very uncomfortable. In addition to the bad rash, a case may involve severe pain, fever, an upset stomach, or headaches. But the pain from postherpetic neuralgia can make life miserable for months, even years.

You'd think that any vaccine that could spare people from this would be welcomed with open arms — and rolled-up sleeves. But it hasn't quite worked out that way. Doctors and health plans haven't pushed it. Some patients have had a hard time getting it. There's some confusion about whether people who have already had shingles should receive it. And for a vaccine, it's expensive.

|

Shingles vaccine: A containment policy

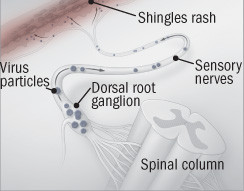

Shingles occur when latent herpes virus particles "escape" a dorsal root ganglion and travel along sensory nerves to the skin.

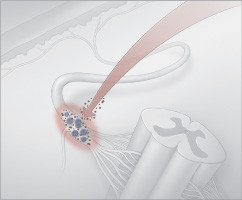

The shingles vaccine revs up the immune system to pounce on the virus as it begins to escape so it can't travel along nerves. |

Here are some of the problems that the shingles vaccine has run into:

Maybe not a great deal after all. Merck is charging about $150 for the one-shot vaccine. Doctors and hospitals charge a mark-up, so the total bill can come close to $300. In comparison, the standard flu vaccine costs between $11 and $15, and the pneumococcal vaccine, about $25. Traditionally, vaccines are one of the best health bargains out there — a low up-front cost that pays for itself many times over in averted sickness and early death. But vaccine costs are going up, so the economics aren't so clear-cut anymore. A cost-effectiveness analysis of Zostavax published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2006 put it in the intermediate cost-effectiveness category.

Spotty insurance coverage. Naturally, as the cost of a vaccine increases, so do the reservations of insurance companies and health plans about covering it. Zostavax is approved for people 60 and older, so Medicare coverage is a major issue. According to the Medicare Rights Center in New York City, Medicare medical coverage (Part B) currently covers the flu, pneumococcal, and hepatitis B vaccines. But it's up to each individual Part D prescription plan to decide whether the shingles vaccine should be on its formulary.

Questionable value for people who have had shingles. When the federal government's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that people who have had shingles get the vaccine, it did so partly because people are sometimes diagnosed with shingles when they don't have it. But if you've had a bona fide case of shingles, the chances of getting another one are extremely low. For that reason, Kaiser Permanente, the California health plan, decided not to offer the vaccine to people who have had shingles.

Logistical problems. Zostavax must be stored at a temperature of 5° F (−15° C). Most doctors who see adult patients don't have a freezer that will keep the vaccine that cold, so some hospitals have set up centralized by-appointment-only Zostavax clinics, staffed by pharmacists. For patients, this can mean making an additional trip to the hospital.

Lack of urgency. Vaccines have traditionally targeted communicable diseases, so getting immunized has a social purpose: You're protecting yourself and others that you might infect with a contagious disease. People with shingles can infect others with the herpes virus that causes the disease (the result is chicken pox, not shingles). Still, shingles is less contagious — and far less lethal — than flu, measles, and many other diseases we get vaccinated for.

Did the FDA play down the benefits? One of the most impressive results from the Shingles Prevention Study that led to approval of the vaccine was the two-thirds reduction in postherpetic neuralgia. But the two-thirds figure — more precisely, 67% — doesn't appear anywhere in the FDA-approved information about Zostavax. Dr. Michael Oxman, head of the Shingles Prevention Study, has complained to the FDA that it used the wrong statistics and played down the vaccine's benefits. Still, not everyone is convinced Zostavax is a blockbuster. Despite the impressive reductions in relative risk, you'd have to vaccinate 370 people to prevent a single case of postherpetic neuralgia over the next three years. Is that a good use of health care dollars? The numbers do look better if you factor in that the immunity lasts longer than three years.

|

Should you get the shingles vaccine? You can't get shingles unless you've first had chicken pox. Currently, more than 90% of adult Americans have had chicken pox, and about one in three will get shingles some time in their lives. The vaccine cuts the risk of developing shingles by half. Adverse reactions to the vaccine don't seem to be a huge problem. A small group of people get a rash around the injection site. There's always the possibility, though, that more serious side effects will emerge as an issue as more people get the vaccine. Your age is a consideration. The vaccine is approved for people 60 and over. The likelihood of getting shingles increases with age. But there's the rub, because the older you are, the less effective the vaccine is against shingles. It's complicated, though. For many people, the worst part of shingles is the pain from the postherpetic neuralgia that develops after shingles. Results from the largest clinical trial of the vaccine showed that it was actually more effective in preventing postherpetic neuralgia in people 70 or older than in those age 60 to 69. Experts we've talked to say once the immune system has been primed by shingles, trying to prime it further with the vaccine doesn't accomplish much, especially in the years following an attack. But the shingles-induced immunity may taper off, so depending on how long ago you had shingles, there might be some value to getting the vaccine. Finally, there's the cost to consider. If you want the vaccine, you need to check whether it is covered by your health plan or Part D Medicare prescription plan first. Coverage is by no means universal. If you have to pay for it out of pocket, you may want to reconsider and take your chances. |

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.