Uncovering the link between emotional stress and heart disease

The brain's fear center may trigger inflammation and lead to a heart attack. But stress reduction techniques can break the chain.

Image: © Cardiology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital

A small, almond-shaped area deep inside the brain called the amygdala is involved in processing intense emotions, such as anxiety, fear, and stress. Now, a new brain-imaging study reveals how heightened activity in the amygdala may trigger a series of events throughout the body that raises heart attack risk.

"This study identifies a mechanism that links stress, artery inflammation, and subsequent risk of a heart attack," says study leader Dr. Ahmed Tawakol, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. Earlier animal studies have shown that stress activates bone marrow to make white blood cells. These infection-fighting cells trigger inflammation, a process that encourages the buildup of fatty plaque inside artery walls. "But what we didn't know was, does this happen in humans? And what is the role of the brain?" he says.

To find out, he and colleagues analyzed data from 293 people who had undergone special imaging tests called PET/CT scans, which were done mostly for cancer screening. The tests used a radioactive tracer that can measure activity within specific areas of the brain and also reveal inflammation in the arteries. None of participants had active cancer or heart disease at the time of the scan. During the follow-up, which lasted two to five years, 22 people experienced one or more cardiovascular events, such as angina (chest pain), heart attack, or stroke.

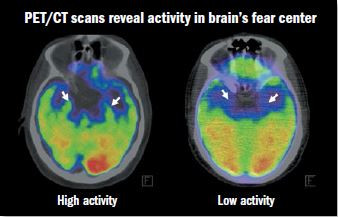

The white arrows in these brain scans point to the two parts of the amygdala. In the left scan, the brighter areas (in green) show higher levels of amygdalar activity. Increased activity is linked to greater levels of perceived stress and heart attack risk.

An overactive amygdala?

The study results, published in the Jan. 11, 2017, issue of The Lancet, found that heightened activity in the amygdala was linked to increased bone-marrow activity, inflammation in the arteries, and a higher risk of heart attack or other cardiovascular events. The association remained even after investigators adjusted for other factors that affect heart disease risk, such as high blood pressure and diabetes. Amygdalar activity also shed light on the timing of the events, as people with higher amygdalar activity experienced events sooner.

Both the size and the activity of the amygdala vary from person to person, but people with anxiety and stress disorders tend to have higher levels of amygdalar activity. Often called the brain's fear center, the amygdala helps people sense and evaluate external stress and mount an internal physiological response, explains Dr. Tawakol.

The Lancet article also reported findings from a separate study of 13 people with post-traumatic stress disorder. They filled out questionnaires designed to assess their current stress levels and underwent the same scans. Higher perceived stress levels went hand in hand both with greater activity in the amygdala and increased inflammation in the arteries.

Stress-reducing strategies

The encouraging news is that techniques that reduce stress such as meditation and yoga may dampen excess activity in the amygdala, research suggests. And several small studies hint that stress-busting strategies can reduce cardiovascular events. One focused on people in cardiac rehabilitation, a program of supervised exercise training and heart-healthy practices for people recovering from heart-related events or surgeries. Those assigned to "enhanced" cardiac rehab — which included small-group discussions and training in stress reduction, coping skills, and relaxation techniques — had far fewer cardiac events during the three years after rehab than those in standard rehab or those who chose not to do rehab.

This growing evidence, coupled with his latest findings, has prompted Dr. Tawakol to ask his patients about their stress levels and, in some cases, refer them to a stress management program at the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine (see "A SMART way to ease stress"). "Large randomized trials are still needed to confirm that treating stress reduces heart disease rates," says Dr. Tawakol. But in the meantime, it's reasonable to recommend stress reduction for people with substantial stress and a high risk of heart disease, since it might help, and it doesn't pose any risk. Stress-reduction techniques have been studied on a range of different ailments with no evidence of any untoward effects, he notes.

We often say we need to "deal" with our stress, as if it's just a nuisance we have to tolerate, says Dr. Tawakol. But we probably need to change our mindset to focus on treating stress if it's indeed as toxic as we are now realizing, he adds.

As for himself, getting lots of exercise is his favorite way to relieve stress, but he finds that mindfulness techniques and getting a good night's sleep also help. "As I've learned more about the science of stress, I've taken more steps to lessen my own stress. I need to practice what I recommend to my own patients," he says.

A SMART way to ease stressThe Harvard-affiliated Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital offers a range of programs to help people enhance their quality of life and cope with different medical conditions. The Stress Management and Resilience Training (SMART) program teaches self-care practices that help buffer daily stress and foster resilience — the ability to cope with stress. During individual and group sessions, people learn about stress and its connection to physical or emotional problems. The program also emphasizes importance of healthy eating, restorative sleep, and physical activity. One key focus is learning a variety of techniques to elicit the relaxation response, which is the opposite of the stress response. First identified in the 1970s at Harvard Medical School by cardiologist Dr. Herbert Benson, the relaxation response can be elicited in many ways, including meditation or repetitive prayer. But you can evoke this calming response with two simple steps:

Practicing these two steps for 10 to 20 minutes a day may help reduce the effects of stress on your body. |

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.