Tiny pumps can help when heart failure advances

Left ventricular assist devices support the heart while waiting for — or in place of — a heart transplant.

What can be done for a failing heart when medications no longer help? A transplant is one option, but there aren't nearly enough donor hearts to meet the need. An artificial heart may someday fill the void, but one isn't yet ready for widespread use.

Small pumps the size of two D batteries offer hope and help today for thousands of people with advanced heart failure. These pumps, known as ventricular assist devices, have been around in one form or another for years. But advances in engineering and medical technology have made them small enough for almost anyone and portable enough to let their users take a walk, go shopping, and even travel. The devices don't work magic, and they come with big personal and financial costs. But they can offer months or years of extra life for people with failing hearts.

Of the dozens of left ventricular assist devices implanted in 2010, the one that former Vice President Dick Cheney received is raising the profile of this intriguing technology.

Key points

|

Pump mechanics

As the name implies, ventricular assist devices help the heart's lower chambers pump blood. The ones most commonly used today for heart failure support the left ventricle.

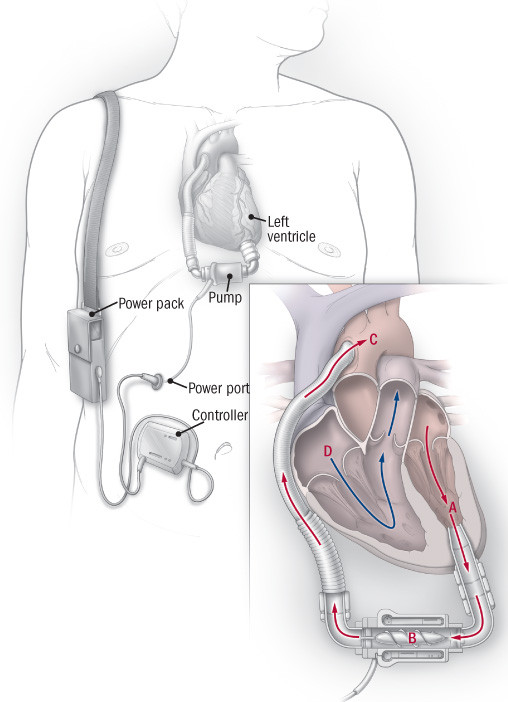

A surgeon places the pump in the abdomen, then connects its inflow tube to the bottom of the left ventricle and its outflow tube to the beginning of the aorta, blood's main pipeline from the heart to the rest of the body (see illustration). Blood from the lungs enters the left side of the heart. The ventricular assist device pulls this oxygen-rich blood into one side of the pump and propels it out of the other side, into the aorta. Although the heart continues to beat normally, the pump moves blood in a continuous fashion, eliminating the pulse we so often associate with healthy blood flow.

Giving the heart a mechanical assist

A left ventricular assist device has four main parts: the pump, a power supply cord, a controller, and a power pack. One end of the pump is implanted directly into the left ventricle; the other is attached to the aorta. Oxygen-rich blood is pulled out of the left ventricle (A) and into the pump (). It is then propelled into the aorta (C) and out to the rest of the body. The right side of the heart (D) continues to function normally. |

The device gets its power from outside the body. When the user is sitting or sleeping, he or she plugs it into a power station. Otherwise, portable batteries run the pump for 10 hours or more at a stretch, allowing the user to go to the store, dance, garden, and do other normal, mobile activities.

Getting electricity from the power source to the pump is the device's Achilles' heel. Most models use an insulated wire that crosses the abdominal wall. The tiny opening for the wire can act as a portal through which infection-causing microbes sneak inside the body. Researchers are trying to find a way to power the pump by transmitting energy waves through the skin, but such a transcutaneous delivery system hasn't yet been perfected.

Three main usesLeft ventricular assist devices are used in three situations: Temporary recovery. When a heart attack, massive infection, or catastrophic emotional shock stuns the heart and shuts down the left ventricle, temporarily placing a left ventricular assist device can help the heart rest, heal, and recover its strength and pumping power. Waiting for a donor heart. The shortage of donor hearts (fewer than 3,000 per year for more than 100,000 people with life-threatening advanced heart failure) means long waits. A left ventricular assist device can keep a person alive until a heart transplant becomes possible. Final destination. Many people who need a new heart don't qualify for one because they have cancer, kidney disease, or another life-shortening condition. For them, left ventricular assist devices are now being used as so-called destination therapy. |

A difficult choice

Although left ventricular assist devices appear to be just what the doctor ordered for thousands of people with advanced heart failure, they come with huge costs for the recipient, his or her family, and the health care system.

Implanting one of these devices requires open-heart surgery, which can pose problems even for relatively healthy individuals. Most people who need a device are older and have other health conditions, making the operation extra hazardous. The pump makes blood more likely to form clots, which can lead to stroke or cause the device to stop working. Taking warfarin (Coumadin) helps prevent clots, but it carries its own set of problems. Infection is common and worrisome, since germs can get inside the body through the power port. The power packs and power line must be kept dry, so showering or bathing becomes a hassle. Then there are worries about losing power at home, faulty batteries, and other malfunctions. Partners, spouses, or other family members or caretakers share some of the managerial and emotional burden.

The financial cost of left ventricular assist devices is equally enormous. The price tag for one left ventricular assist device and its associated equipment, the operation to implant it, the week-long recovery time in the hospital, and the follow-up medical care is close to $200,000.

How long the devices will work is another big uncertainty. Although one recipient lived with his for seven years, the average is likely to be less than that.

Providing options

A left ventricular assist device offers a bridge to the future for different groups of people with advanced heart failure (see "Three main uses"). The biggest group by far includes people who aren't candidates for a heart transplant. This use of a left ventricular assist device is called destination therapy. The FDA has approved one ventricular assist device, the HeartMate II, for destination therapy, and Medicare has agreed to pay for destination therapy under certain circumstances.

"Using these devices while waiting for a donor heart or for what's called destination therapy is really using them as a bridge to decision," says Dr. Gilbert H. Mudge, Jr., medical director of the Partners Heart Failure Management Program at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. That's because in some people, use of the device has allowed the heart to recover enough so they no longer need the device or a transplant. A left ventricular assist device could also someday work with stem cell therapy, giving the heart time to heal and recover as stem cells rebuild weakened or damaged heart muscle.

Disclaimer:

As a service to our readers, Harvard Health Publishing provides access to our library of archived content. Please note the date of last review or update on all articles.

No content on this site, regardless of date, should ever be used as a substitute for direct medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician.